posted by Phil Johnson

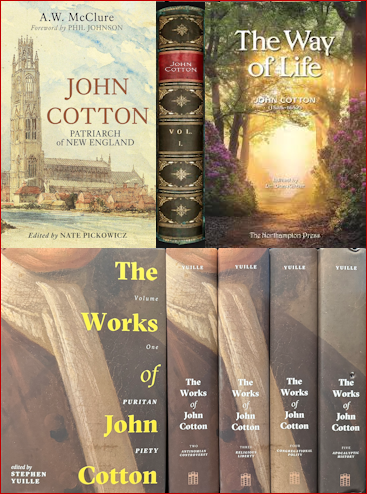

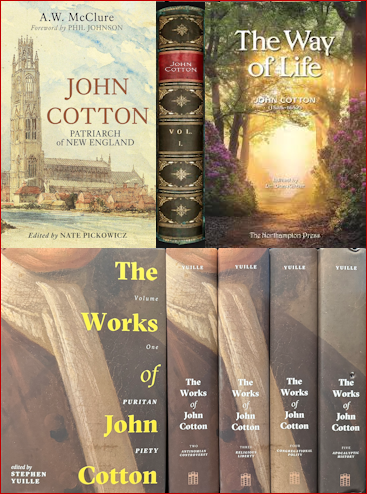

I wrote this piece as a foreword to Nate Pickowicz's edition of John Cotton: Patriarch of New England. It's an excellent, breif biography of America's first, and arguably greatest, Puritan.

For an affordable introduction to Cotton's works, I recommend Cotton's The Way of Life, published by the Northampton Press, edited by Don Kistler.

But if you want to dig deep, you absolutely must have this five-volume set: The Works of John Cotton, published by Soli Deo Gloria, and edited by Stephen Yuille.

|

|

mong the luminaries of the early Puritan era, none shines brighter than John Cotton. He possessed a remarkable array of spiritual gifts and academic accomplishments. He was a brilliant scholar, a master of the biblical languages, a skilled and perceptive theologian, a proficient writer, a powerful preacher, a tenderhearted pastor, a wise and sympathetic counselor, and an effective evangelist. He had lengthy ministries both in England and in colonial Massachusetts. On both sides of the Atlantic he managed to gain profound and lasting respect from friends and adversaries alike. His character and personality shaped the unique flavor of American Puritanism more than any other single influence. The very best qualities we see among the Puritans of early Massachusetts— their humble piety, their emphasis on sin and repentance, their strong work ethic, their sense of duty to God and community, and their love for Christ and Scripture—all are part of John Cotton's legacy.

mong the luminaries of the early Puritan era, none shines brighter than John Cotton. He possessed a remarkable array of spiritual gifts and academic accomplishments. He was a brilliant scholar, a master of the biblical languages, a skilled and perceptive theologian, a proficient writer, a powerful preacher, a tenderhearted pastor, a wise and sympathetic counselor, and an effective evangelist. He had lengthy ministries both in England and in colonial Massachusetts. On both sides of the Atlantic he managed to gain profound and lasting respect from friends and adversaries alike. His character and personality shaped the unique flavor of American Puritanism more than any other single influence. The very best qualities we see among the Puritans of early Massachusetts— their humble piety, their emphasis on sin and repentance, their strong work ethic, their sense of duty to God and community, and their love for Christ and Scripture—all are part of John Cotton's legacy.

During the first decade of the seventeenth century, John Cotton was a lecturer and catechist at Emmanuel College, Cambridge University (a Puritan training institution for pastors). Though he was highly esteemed for his eloquence and erudition, Cotton himself was not yet genuinely converted. A sermon by Richard Sibbes in 1609 truly awakened his heart to believe, and the transformation was immediate and obvious to all. The trademark eloquence of Cotton's lectures gave way to a simple but passionate style of gospel-focused preaching designed not to impress fellow scholars, but rather to awaken the consciences of his hearers. The need for sound conversion is one of the central themes that reverberates through all of Cotton's subsequent sermons and writings.

His fondness for gospel truth was both winsome and infectious. Wherever he preached, people were convicted and converted. A thoroughgoing Calvinist, he powerfully refutes the opinion of those who insist that the doctrine of election is an impediment to evangelism. He was a zealous and effective winner of souls. Just a few months after Cotton's ordination to the ministry in colonial Massachusetts, the First Church of Boston saw a wave of remarkable conversions that can only be termed revival. Governor Winthrop wrote,

It pleased the Lord to give special testimony of his presence in the church of Boston, after Mr. Cotton was called to office there. More were converted and added to that church, than to all the other churches in the bay. . . . Divers profane and notorious evil persons came and confessed their sins, and were comfortably received into the bosom of the church.

It is of course extraordinary that a renowned theologian, scholar, and long-tenured pastor of John Cotton's stature and age (he was nearly 50) would leave everything he knew in order to help establish a colony in the brutal frontier of the New World. How John Cotton came to Massachusetts is one of the central threads in the story of his remarkable life. You can't read any biographical account of John Cotton without noticing the amazing way Providence sovereignly directed this amazing spiritual leader into a role he might never have chosen for himself—and thus magnified his influence and his legacy through circumstances that would have seemed more likely to sideline him or bury his name in obscurity.

Cotton's legacy lives on. His life is instructive even today.

There are, for example, profound lessons about separatism and schism woven into John Cotton's experience. We learn from his struggle with the Church of England that cautious, biblical separatism (2 Corinthians 6:14-18; Revelation 18:4) is sometimes necessary. On the other hand, Cotton himself correctly believed that the schismatic mentality of those who think every disagreement and every error deserves a harsh anathema is destructive to the health and testimony of the church. Faithful believers need to foster both wise biblical discernment and a unifying love for the true Bride of Christ.

This is vividly illustrated not only in John Cotton's failed struggle to remain in and influence the Church of England, but also in his well-documented conflicts with Roger Williams. Williams was a strict separatist who refused communion with the Puritan churches of Massachusetts because they declined to condemn the Church of England as a synagogue of Satan. His views about the church, her purity, her unity, and her role in society set Williams bitterly at odds with John Cotton.

Both John Cotton and Roger Williams had valid points to make. For example, Williams alleged that the churches and the government of early Massachusetts afforded hardly more freedom of conscience than the Puritans themselves had been given under Archbishop Laud in England. The complaint was not far-fetched. The churches of New England had no problem letting the secular magistrates inflict punishments on people who were excommunicated over matters of conscience. Virtually all evangelicals today would have more sympathy with Williams's view on that point than with Cotton's.

But Williams was unquestionably too censorious, too sharp in his criticism, too prone to exaggerate others' flaws, too ready to impute ill motives to his adversaries, and too quick to break fellowship with men who gave every evidence of genuine faith in Christ and his Word.

Both men's shortsighted prejudices made their disagreement far more bitter than it needed to be.

One conviction that John Cotton is especially remembered for is his defense of Congregationalism. More than fifteen years before sailing for the New World, he had embraced Congregationalism, a system of church polity where each individual church, rather than the presbytery, is responsible for its own affairs. (New England Congregationalism is another key feature of Cotton's legacy.) In 1644, at the height of his conflict with Roger Williams, Cotton published The Keyes of the Kingdom of Heaven, an explanation and defense of Congregationalism. The manuscript was sent by ship to England, where it was published. John Owen, the most eminent of Puritan scholars, obtained a copy in order to write a critique, but upon reading the book, he was converted to John Cotton's point of view. Owen wrote,

In the pursuit and management of [Mr. Cotton's] work, quite beside, and contrary to my expectation, at a time wherein I could expect nothing on that account but ruin in this world, without the knowledge, or advice of, or conference with any one person of that judgment, I was prevailed upon to receive those principles to which I had thought to have set myself in opposition.

He then wryly added, "Indeed this way of impartially examining all things by the word . . . laying aside all prejudiced respects to persons or present traditions, is a course that I would admonish all to beware of who would avoid the danger of being made [Congregationalists]."2

It's a shame John Cotton and Roger Williams didn't take Owen's dispassionate approach to examining one another's views. The two were so different that it's unlikely that either would have fully embraced the other's position, but they certainly could have learned from one another.

That seems an important lesson for Christians living in the polemically charged atmosphere of the Internet age. It's one more thing we need to learn from the life and experience of John Cotton.

The only other significant misstep worth pointing out in the career of John Cotton is his early support for Anne Hutchinson and her followers. In the end, Cotton saw that although she claimed to be echoing his teaching, she had actually taken aspects of his teaching on grace to an unbiblical, antinomian extreme. He wisely distanced himself from the error and took the opportunity to clarify his views through careful teaching on the issues that were under debate.

The deep respect Cotton's contemporaries had for him was well deserved, and he also deserves much credit for the moral and biblical foundations that held colonial Massachusetts together from the time of the colony's founding well into the next century. I would argue that the Great Awakening of Jonathan Edwards' era represented a return to New England's spiritual roots—a harvest that sprang from seeds planted by John Cotton and watered by the next two generations of New England Puritans (including Cotton's son-in-law and grandson, Increase Mather and Cotton Mather).

One cannot make sense of early New England history apart from the Puritan influence that shaped that culture—and John Cotton is the key figure in understanding the doctrine, piety, and spirit of New England Puritanism. My hope is that this book will be an introduction for many readers into the rich spiritual history of early New England. May that in turn stir renewed interest in the great biblical truths that shaped the very embryo of American life and values—and (even more foundationally) the lives of the godly men and women who helped found this great nation.

he followers of the early Reformers were distinguished by the sanctity of their lives. When they were about to hunt out the Waldenses, the French king, who had some of them in his dominions, sent a priest to see what they were like, and he, honest man as he was, came back to the king, and said, "As far as I could find, they seem to be much better Christians than we are. I am afraid they are heretics, but really they are so chaste, so honest, so upright, and so truly pious, that, though I hate heresy—I hope your majesty does not suspect me on that account—yet I would that all Catholics were as good as they are."

he followers of the early Reformers were distinguished by the sanctity of their lives. When they were about to hunt out the Waldenses, the French king, who had some of them in his dominions, sent a priest to see what they were like, and he, honest man as he was, came back to the king, and said, "As far as I could find, they seem to be much better Christians than we are. I am afraid they are heretics, but really they are so chaste, so honest, so upright, and so truly pious, that, though I hate heresy—I hope your majesty does not suspect me on that account—yet I would that all Catholics were as good as they are."

I'm often surprised and not a little shocked by the tone and flavor of some of the discourse on social media among people who self-identify as gospel-believing Christians. I'm not talking only about the annoying busybodies, false accusers, trash-talkers, and all-purpose haters. I'm thinking also of the people who routinely sprinkle their comments with obscene or profane language ("cuss words," as the idiom used to be known). They tend to be fiercely resistant to any criticism or correction of the practice. They think the casual use of salty language shows how "genuine," and "relatable" they are, and this somehow enhances the believability of their testimony.

I'm often surprised and not a little shocked by the tone and flavor of some of the discourse on social media among people who self-identify as gospel-believing Christians. I'm not talking only about the annoying busybodies, false accusers, trash-talkers, and all-purpose haters. I'm thinking also of the people who routinely sprinkle their comments with obscene or profane language ("cuss words," as the idiom used to be known). They tend to be fiercely resistant to any criticism or correction of the practice. They think the casual use of salty language shows how "genuine," and "relatable" they are, and this somehow enhances the believability of their testimony.

hen an enterprise begins in martyrdom, it is none the less likely to succeed; but when conquerors begin to preach the gospel to those they have conquered, it will not succeed; God will teach us that it is not by might.

hen an enterprise begins in martyrdom, it is none the less likely to succeed; but when conquerors begin to preach the gospel to those they have conquered, it will not succeed; God will teach us that it is not by might.

obody wonders that Mahometanism spread. After the Arab prophet had for a little while himself personally borne the brunt of persecution, he gathered to his side certain brave spirits who were ready to fight for him at all odds. You marvel not that the sharp arguments of scimitars made many converts.

obody wonders that Mahometanism spread. After the Arab prophet had for a little while himself personally borne the brunt of persecution, he gathered to his side certain brave spirits who were ready to fight for him at all odds. You marvel not that the sharp arguments of scimitars made many converts. Now, if our Lord had arranged a religion of fine shows, and pompous ceremonies, and gorgeous architecture, and enchanting music, and bewitching incense, and the like, we could have comprehended its growth; but he is "a root out of a dry ground," for he owes nothing to any of these. Christianity has been infinitely hindered by the musical, the æsthetic, and the ceremonial devices of men, but it has never been advantaged by them, no, not a jot. The sensuous delights of sound and sight have always been enlisted on the side of error, but Christ has employed nobler and more spiritual agencies.

Now, if our Lord had arranged a religion of fine shows, and pompous ceremonies, and gorgeous architecture, and enchanting music, and bewitching incense, and the like, we could have comprehended its growth; but he is "a root out of a dry ground," for he owes nothing to any of these. Christianity has been infinitely hindered by the musical, the æsthetic, and the ceremonial devices of men, but it has never been advantaged by them, no, not a jot. The sensuous delights of sound and sight have always been enlisted on the side of error, but Christ has employed nobler and more spiritual agencies.

ouTube and social media are full of AI-produced videos using John MacArthur's voice and image, making him say things that perhaps sound like something you might think he believed, but expressing opinions he never held and making statements he never made. There are dozens of these fake videos floating around, and I am asked about them almost daily.

ouTube and social media are full of AI-produced videos using John MacArthur's voice and image, making him say things that perhaps sound like something you might think he believed, but expressing opinions he never held and making statements he never made. There are dozens of these fake videos floating around, and I am asked about them almost daily. My standard reply: "No, those are fake. If you want to be certain you are hearing something John MacArthur actually said; or if you are looking for a video or audio recording of John's that you can trust to be genuine, you'll find it at

My standard reply: "No, those are fake. If you want to be certain you are hearing something John MacArthur actually said; or if you are looking for a video or audio recording of John's that you can trust to be genuine, you'll find it at  John was never a fan of Siri or Alexa, and he certainly did not want to lend his face, voice, or personality to an AI-generated cyber-pastor or digital rabbi. The idea of an artificial John MacArthur saying fake prayers for people with real needs absolutely appalled him—perhaps even more than it appalled the rest of us.

John was never a fan of Siri or Alexa, and he certainly did not want to lend his face, voice, or personality to an AI-generated cyber-pastor or digital rabbi. The idea of an artificial John MacArthur saying fake prayers for people with real needs absolutely appalled him—perhaps even more than it appalled the rest of us.

he power and grace of God will be conspicuously seen in the subjugation of this world to Christ: every heart shall know that it was wrought by the power of God in answer to the prayer of Christ and his church. I believe, brethren, that the length of time spent in the accomplishment of the divine plan has much of it been occupied with getting rid of those many forms of human power which have intruded into the place of the Spirit.

he power and grace of God will be conspicuously seen in the subjugation of this world to Christ: every heart shall know that it was wrought by the power of God in answer to the prayer of Christ and his church. I believe, brethren, that the length of time spent in the accomplishment of the divine plan has much of it been occupied with getting rid of those many forms of human power which have intruded into the place of the Spirit. If you and I had been about in our Lord’s day, and could have had everything managed to our hand, we should have converted Cæsar straight away by argument or by oratory; we should then have converted all his legions by every means within our reach; and, I warrant you, with Cæsar and his legions at our back we would have Christianised the world in no time: would we not? Yes, but that is not God’s way at all, nor the right and effectual way to set up a spiritual kingdom. Bribes and threats are alike unlawful, eloquence and carnal reasoning are out of court, the power of divine love is the one weapon for this campaign.

If you and I had been about in our Lord’s day, and could have had everything managed to our hand, we should have converted Cæsar straight away by argument or by oratory; we should then have converted all his legions by every means within our reach; and, I warrant you, with Cæsar and his legions at our back we would have Christianised the world in no time: would we not? Yes, but that is not God’s way at all, nor the right and effectual way to set up a spiritual kingdom. Bribes and threats are alike unlawful, eloquence and carnal reasoning are out of court, the power of divine love is the one weapon for this campaign.

hen Mahomed would spread his religion, he bade his disciples arm themselves, and then go and cry aloud in every street, and offer to men the alternative to become believers in the prophet, or to die. Mahomed's was a mighty voice, which spake with the edge of the scimitar. He delighted to quench the smoking flax, and break the bruised reed; but the religion of Jesus has advanced upon quite a different plan.

hen Mahomed would spread his religion, he bade his disciples arm themselves, and then go and cry aloud in every street, and offer to men the alternative to become believers in the prophet, or to die. Mahomed's was a mighty voice, which spake with the edge of the scimitar. He delighted to quench the smoking flax, and break the bruised reed; but the religion of Jesus has advanced upon quite a different plan.

mong the luminaries of the early Puritan era, none shines brighter than John Cotton. He possessed a remarkable array of spiritual gifts and academic accomplishments. He was a brilliant scholar, a master of the biblical languages, a skilled and perceptive theologian, a proficient writer, a powerful preacher, a tenderhearted pastor, a wise and sympathetic counselor, and an effective evangelist. He had lengthy ministries both in England and in colonial Massachusetts. On both sides of the Atlantic he managed to gain profound and lasting respect from friends and adversaries alike. His character and personality shaped the unique flavor of American Puritanism more than any other single influence. The very best qualities we see among the Puritans of early Massachusetts— their humble piety, their emphasis on sin and repentance, their strong work ethic, their sense of duty to God and community, and their love for Christ and Scripture—all are part of John Cotton's legacy.

mong the luminaries of the early Puritan era, none shines brighter than John Cotton. He possessed a remarkable array of spiritual gifts and academic accomplishments. He was a brilliant scholar, a master of the biblical languages, a skilled and perceptive theologian, a proficient writer, a powerful preacher, a tenderhearted pastor, a wise and sympathetic counselor, and an effective evangelist. He had lengthy ministries both in England and in colonial Massachusetts. On both sides of the Atlantic he managed to gain profound and lasting respect from friends and adversaries alike. His character and personality shaped the unique flavor of American Puritanism more than any other single influence. The very best qualities we see among the Puritans of early Massachusetts— their humble piety, their emphasis on sin and repentance, their strong work ethic, their sense of duty to God and community, and their love for Christ and Scripture—all are part of John Cotton's legacy.