What mediocre preacher said this?

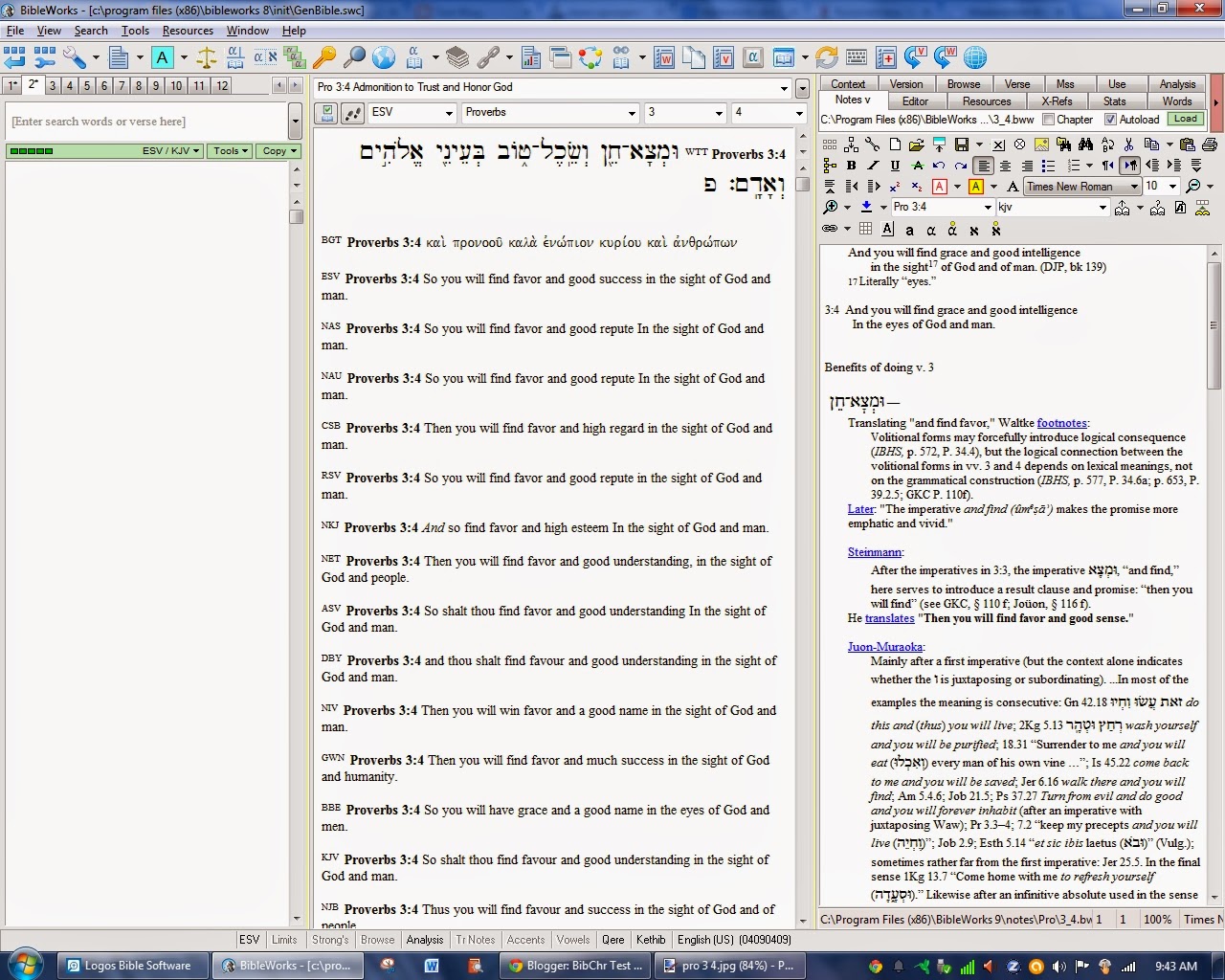

It is a long time since I preached a sermon that I was satisfied with. I scarcely recollect ever having done so.If you didn't suspect a trick-question, you might speculate, "You, DJP?" — a fair and appropriate guess. But no, the mediocre preacher was Charles Haddon Spurgeon, in a sermon titled "Good Earnests of Great Success," preached in 1868 (thanks to Dave Harvey, whose post brought this to my attention).

Spurgeon goes on:

You do not know, for you cannot hear my groanings when I go home, Sunday after Sunday, and wish that I could learn to preach somehow or other; wish that I could discover the way to touch your hearts and your consciences, for I seem to myself to be just like the fire when it wants stirring; the coals have got black when I want them to flame forth.

If I could but say in the pulpit what I feel in my study, or if I could but get out of

my mouth what I have tried to get into my own soul, then I should preach indeed, and move your souls, I think. Yet perhaps God will use our weakness, and we may use it with ourselves, to stir us up to greater strength. You know the difference between slow motion and rapidity. If there were a cannon ball rolled slowly down these aisles, it might not hurt anybody; it might be very large, very huge, but it might be so rolled along that you might not rise from your seats in fear. But if somebody would give me a rifle, and ever so small a ball, I reckon that if the ball flew along the Tabernacle, some of you might find it very difficult to stand in its way. It is the force that does the thing.

So, it is not the great man who is loaded with learning that will achieve work for God; it is the man, who, however small his ability, is filled with force and fire, and who rushes forward in the energy which heaven has given him, that will accomplish the work—the man who has the most intense spiritual life, who has real vitality at its highest point of tension, and living, while he lives, with all the force of his nature for the glory of God. Put these three or four things together, and I think you have the means of prosperity. [Paragraph breaks added]Were I interviewed on truths that loom larger and larger over the decades, particularly regarding preaching, I know what would come near the top. It is this: the centrality and native impotence of preaching.

No reader of Pyromaniacs will need convincing of the former. It is the "preacher" who brings the word that saving faith requires (Romans 10:14, 17), and through the folly of what we preach that God saves sinners (1 Corinthians 1:21). Our paramount and awesome imperative, as pastors, is to "Preach the Word" regardless of opposition (2 Timothy 4:2, with context).

How, then, can I speak of the impotence of preaching?

My readiest answer is "From experience!" But let me back up. As a young Christian man and a beginning preacher, so high was my estimate of the Word of God that I virtually saw it as a magic book. Here's what I mean: Hebrews 4:12 was a central verse, with its declaration that "The word of God is living and effective and sharp beyond any two-edged sword," piercing where nothing else can reach. There it is. That book is full of divine power.

I still utterly believe that, more than ever. But the way I rather expected it to work was virtually ex opere operato. That is, you preach the Word, and wonderful things happen. Every time. Kazingo. Just by doing it. Because the Word is so inherently powerful.

As with all error, there is truth in all of that. Something does happen. Both preacher and hearer now stand under the testimony of God. It counts. Whether we repent or reject, whether we mourn or mock, whatever our response, God has spoken. He is on record; and His speaking to us is on our record.

As with all error, there is truth in all of that. Something does happen. Both preacher and hearer now stand under the testimony of God. It counts. Whether we repent or reject, whether we mourn or mock, whatever our response, God has spoken. He is on record; and His speaking to us is on our record.But what was not prominent enough in my thinking was the absolutely and constantly essential ministry of the Triune God, whether the hearers are saved or unsaved. The work of conversion, of blessing, of edification, completely and utterly depends on God attending, using, and applying His word with power (cf. 1 Thessalonians 1:5; 2:13).

Consider this: Paul preached Christ. Lydia believed. Yay, there you have it, Hebrews 4:12! Yes indeed — but other ladies present did not believe. Uh-oh. Why not? Because "the Lord opened [Lydia's] heart to pay attention to what was said by Paul" (Acts 16:14b), and He did not do that for the others who heard the exact same preaching.

Was the fault Paul's? Had he done a better job, given a better altar-call, furnished a glossier Anxious Bench, could he have produced more responses? Well, maybe so; but he couldn't have opened more hearts.

This is the vital and indispensable element: the work of God behind, in, with, above, through, and often despite our preaching. It is the vital element, and it is the element we cannot control or produce by formula. We can only plead and beseech Heaven, that God would move His hand, and work to His glory.

Until and unless that happens, we are like Elijah on Mt. Carmel. By the very best of our preparation and passion, we can lay plenty of wood. And by our innumerable flaws and idiocies and patheticalities, we will surely drench the wood with abundant water.

Until and unless that happens, we are like Elijah on Mt. Carmel. By the very best of our preparation and passion, we can lay plenty of wood. And by our innumerable flaws and idiocies and patheticalities, we will surely drench the wood with abundant water.But the fire?

That must come from Heaven, or it will not come at all.

This is a truth that Charles Spurgeon, probably the greatest preacher ever to use the English language, grasped and believed. John Stott (no slouch as a preacher) relates the story that Spurgeon, as he climbed the steps to his pulpit, regularly repeated over and over "I believe in the Holy Ghost, I believe in the Holy Ghost."

So must we, consciously and in great, pleading, abject dependence.

How? I'll close with a few specific exhortations:

- The pastor himself must pray as he works on his sermon. I knew a preacher who would not prepare at all, because he felt that the Holy Spirit needed to give him the word on the spot. I wondered, "Couldn't the Holy Spirit have helped you on Monday, and Tuesday, as you worked on a message?" Of course He can, and does.

- The pastor himself should pray for the work of God before, during, and after the delivery of the sermon. I confess I am still learning this...along with everything else worth learning.

- But the congregation must also join in. Paul often pled for his converts' and readers' prayers for his ministry of the Word (cf. Colossians 4:3-4; 2 Thessalonians 3:1). So attend your church's midweek prayer meeting, and join your brothers and sisters in opening your mouth in prayers for conversions, for conviction, for instruction, for transformation through the ministry of the Gospel and Word. Then on Sunday, take time before the service starts to find your seat and begin praying for yourself and others, for your pastor, and for the effective ministry of the Word.

But no, think again. Do not imagine that even the very best preacher's sermon will accomplish any more than a snowball in the Sahara, apart from the hand of God on it. And that's where you are called to come in, and wrestle alongside him in your prayers (Romans 15:30; 2 Corinthians 1:11).

Paul knew it, Spurgeon knew it. Let us know it as well.