Dr. Russell Moore is my fellow blogger at firstthings.com's Evangel blog, and a well-respected speaker, pastor, and professor at SBTS. He is, in every way, my better, and an example of Christian virtue which I could never be. He is to be widely-admired by the church as a teacher and as a man with a gigantic heart for the lost. His blogging and other writing on the subject of reaching the lost, and on adoption, has been instructive to me, especially when it comes to the matter of dealing with the messy work of pastoring people through their broken lives in the lifelong task of sanctification.

Yesterday, he posted a brief blog entry regarding his thoughts on Anne Rice's recent rejection of Christianity "in the name of Christ". That is, she declared her allegiance to Christ and therefore denounced all Christianity as her best thought on how to deal with the other Christians she witnessed.

Here's the crux of Dr. Moore's 2-page essay:

Anne Rice hasn’t rejected you. Anne Rice hasn’t betrayed you. Would you pray for her, and for the other smoldering wicks and about-to-bolt potential prodigals in your church (and maybe in your home)? It could be Anne has been deeply hurt by what she has seen in Christianity. Or it could be that, like Jesus’ disciples, the closer she’s drawing to Christ, the more she is made uncomfortable by it. Let’s love her.The sentiment here is well-meant, and pastorally-intentioned. Of course let's please pray for Anne Rice -- at the very least for the same reason we pray without ceasing for all people, but specifically because her experience is an interesting one which, it seems to me, is not very well understood.

Back in 2005 when she went public with her return to Catholicism, I blogged a bit about her confession of faith and her book Out of Egypt. That book in particular seems to me to be extremely instructive as to what Mrs. Rice experienced -- which was more a bout with intellectual honesty than a turn of faith and repentance.

Because the diversion is brief, I'd encourage you to read those three posts as background to this subject.

However, in doing that, I think that background causes me to wonder whether Dr. Moore is giving truly-pastoral advice, or has merely sentimentalized an approach to this sort of behavior.

It seems to me that Mrs. Rice was very able and willing, in 2005, to turn a thoughtful and critical eye to the common objections to the actual story of the Gospel. She was able to make the critical case against liberal readings of the Gospels because let's face it: she's a literate woman. She read the stories as they were told, and found the case against them to be entirely shallow from a literary, hostorical and academic standpoint.

I choose the word "critical" here specifically because I do not think her effort was "apologetic" in the least -- she was not seeking to give an answer for the hope that lies within her, but was in fact narrating the story of her own coming to terms with the story of Jesus. She was giving an academic assessment of non-christian readings of the Gospels, and found them wanting.

This caused her, in her own words, to return to Catholicism -- the religion of her childhood. And in that, she has also stood up for her own belief in the resurrection of Jesus -- which ought to be no surprise. One of her tour guides through the NT literature is N.T. Wright who, in spite of everything else you might say about him, probably writes most vivaciously about the fact of the bodily resurrection of Christ among everyone in the last 200 years. I mean: he's the guy who coined the term, "the life after life-after-death" to make clear what it is the Christian hope truly is.

So yes: she's all about some reverence for the Gospels as compelling stories about Jesus. And yes: she's all about a resurrection. But let's face it: this week, she made it clear she is also, before all that, about these things:

For those who care, and I understand if you don't: Today I quit being a Christian. I'm out. I remain committed to Christ as always but not to being "Christian" or to being part of Christianity. It's simply impossible for me to "belong" to this quarrelsome, hostile, disputatious, and deservedly infamous group. For ten years, I've tried. I've failed. I'm an outsider. My conscience will allow nothing else. [28 July 2010, 12:36 PM]It's curious that this is a matter of conscience for her. What does that mean, I wonder? It seems to me that this is entirely a moral issue for her -- to be apart from the group "Christianity" because that group is "quarrelsome, hostile, disputatious, and deservedly infamous." I think the primary question to ask, though, is if this is actually true of Christianity -- is it "deservedly-infamous"? Would Dr. Moore own that statement?

I think probably not -- and he would point out that Mrs. Rice's indictment here is primarily emotive. Her accusations aren't primarily rational but visceral for the sake of another agenda -- so taking this statement to task is not actually very wise because it sets the emotive nature of the statement up for defensive behavior, and for taking reproaches as hostility rather than good advice.

To that I say: fair enough. Maybe it was essentially a "bad day" for Mrs. Rice -- or a "bad 10 years", since that's the scope of her complaint. But hard upon that compaint is this one:

As I said below, I quit being a Christian. I'm out. In the name of Christ, I refuse to be anti-gay. I refuse to be anti-feminist. I refuse to be anti-artificial birth control. I refuse to be anti-Democrat. I refuse to be anti-secular humanism. I refuse to be anti-science. I refuse to be anti-life. In the name of Christ, I quit Christianity and being Christian. Amen. [28 July 2010, 12:41 PM]

This is her list of moral objections -- and as such they are accusations against Christianity, specifically Catholicism (a conflation I'll get to in a minute): it is anti-gay (meaning, I suppose, that it forbids gay marriage and at least formally sets sanctions against homosexual behavior and lifestyles); it is anti-feminist (which, I think, is a radicalization of the term as there is no institution in the history of the world which has done more for women socially than the Christian church -- however, I think she probably means that it forbids women as spiritual leaders, and that she also means something relating to "legal, safe and rare" abortions); anti-birth control (again, I think this is about abortion, but it's also a feminist tent pole that women are oppressed if they must have all the children the sex they participate in conceives); anti-Democrat (I sense a pattern …); anti-secular humanism (a phrase which fits into the flow of the complaints in that it ostensibly points to the greatest common good for mankind through human achievement); anti-science (I infer her to mean anti-stem-cell research, which again is in a specific pattern); and of all things after this list, "anti-life".

This is her list of moral objections -- and as such they are accusations against Christianity, specifically Catholicism (a conflation I'll get to in a minute): it is anti-gay (meaning, I suppose, that it forbids gay marriage and at least formally sets sanctions against homosexual behavior and lifestyles); it is anti-feminist (which, I think, is a radicalization of the term as there is no institution in the history of the world which has done more for women socially than the Christian church -- however, I think she probably means that it forbids women as spiritual leaders, and that she also means something relating to "legal, safe and rare" abortions); anti-birth control (again, I think this is about abortion, but it's also a feminist tent pole that women are oppressed if they must have all the children the sex they participate in conceives); anti-Democrat (I sense a pattern …); anti-secular humanism (a phrase which fits into the flow of the complaints in that it ostensibly points to the greatest common good for mankind through human achievement); anti-science (I infer her to mean anti-stem-cell research, which again is in a specific pattern); and of all things after this list, "anti-life".It's this list which makes Dr. Moore's comments puzzling. Martin Luther, of course, wrote, "Our Lord and Master Jesus Christ, when He said Poenitentiam gait, willed that the whole life of believers should be repentance." That is, our life is not the life of kicking at the goads against the God who is Love: it is knowing His will for us and then dying to sin in order to live in His new life. Yet there's not a drop of repentance in Mrs. Rice's statement -- it is in fact the antithesis of repentance because it frames the problem of the speaker in terms which rather impugn others for holding strong convictions which have been, historically, in the necessary middle of the faith and the church. Some might say this is transference by Mrs. Rice. I would say rather that it is a refusal to accept guidance in the practical matter of spiritual formation. She does in fact make "Christians" her enemies by framing them as immoral and irredeemable.

But there is more:

My faith in Christ is central to my life. My conversion from a pessimistic atheist lost in a world I didn't understand, to an optimistic believer in a universe created and sustained by a loving God is crucial to me. But following Christ does not mean following His followers. Christ is infinitely more important than Christianity and always will be, no matter what Christianity is, has been, or might become. [29 July 2010, 4:06 PM][via Facebook]I find it difficult not to say, "aha!" here. I can't really find a euphemism for the kind of pride it takes to say, "My faith in Christ is central to my life," when one has frankly already made it clear that keeping his commands is simply right out.

It is this analysis of what Mrs. Rice has posted via Facebook that Dr. Moore's advice lacks. Should Mrs. Rice be heckled and run around like Servetus in 16th century Europe? Wow -- of course not. But this is not the only option when she has already drawn up the rules of engagement.

The first measure of one's approach has to go back to the problem of Catholicism -- a problem I suspect Dr. Moore would minimize. Could it be that Mrs. Rice was an honest-to-God Christian inside Catholicism? Of course -- I think I am famous for saying that there are many lousy Catholics who have great faith in Christ. But it seems to me that her faith is fully informed by Catholic dogma, and that the flaws in her acting out in faith are frankly the flaws of all thoughtful people inside Catholicism: because you have to disassociate so many unbiblical teachings from your core faith, you wind up dismantling your ability to respect right-minded religious authority. Because the only authority she has says it is infallible but in truth it is riddled with falsehood, she applies her skepticism of claims to infallibility to the Bible and makes it her own buffet of truths. What Mrs. Rice first needs is to be disabused of Catholicism to recover her faith in the church and in God's authority over her moral and intellectual life.

The second measure of approach has to be challenging her deeply regarding moral standards -- as in, if they exist and what they are. Her view of what is moral is a consequential view formed after many other a priori commitments have ben made. For example, how deeply flawed is the view that it's anti-life to be anti-abortion? Is treating this like it is not open antagonism to God's view of murder actually pastorally-, evangelically- or apologetically-useful?

And the third measure is that Mrs. Rice has to meet some people someplace who are actually Christians -- and not just moralists or political activists or attenders at a pep rally every Sunday. She needs to meet some people who are like the people at the end of Acts 2 -- devoted to the apostles’ teaching and the fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers, together with all things in common, selling their possessions and belongings and distributing the proceeds to all, as any had need, and day by day, attending the temple together and breaking bread in their homes, receiving their food with glad and generous hearts, praising God and having favor with all the people. This would be an indictment which should stick to us because it is the one which, all told, we wear daily in spite of knowing better.

If she met people like that, I suspect that she would at least have the integrity to take back the ugly things she said. But Dr. Moore's approach to this seems to me to ensure that nobody would treat her as if she said anything wrong. She has said something wrong, and someone needs to be a true friend to her and tell her the depths of her mistakes here -- which do put her at enmity with God and His people.

But, to close up here, this is where Christianity is above all false religions: those who are our enemies can be reconciled -- in fact, this is the purpose of our faith. Christ died that those who live might no longer live for themselves but for him who for their sake died and was raised. Even though we once regarded Christ according to the flesh, we regard him thus no longer. Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come. All this is from God, who through Christ reconciled us to himself and gave us the ministry of reconciliation; that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation. Therefore, we are ambassadors for Christ, God making his appeal through us. We implore you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God. For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.

But, to close up here, this is where Christianity is above all false religions: those who are our enemies can be reconciled -- in fact, this is the purpose of our faith. Christ died that those who live might no longer live for themselves but for him who for their sake died and was raised. Even though we once regarded Christ according to the flesh, we regard him thus no longer. Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come. All this is from God, who through Christ reconciled us to himself and gave us the ministry of reconciliation; that is, in Christ God was reconciling the world to himself, not counting their trespasses against them, and entrusting to us the message of reconciliation. Therefore, we are ambassadors for Christ, God making his appeal through us. We implore you on behalf of Christ, be reconciled to God. For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.Be reconciled to God, Mrs. Rice. And in that, come prepared to repent for the sake of whom you have believed.

Do you see what I’m saying here? DJP and Josh Harris and Patrick Chan and myself all used Twitter to send a message in a Twitter-sides data stream that Jesus doesn’t want you personally to be a tweet-sized follower of Jesus. You should put down the proverbial net – or in this case, the actual mouse and KB, or your laptop, or your phone or iPhone – and follow Jesus.

Do you see what I’m saying here? DJP and Josh Harris and Patrick Chan and myself all used Twitter to send a message in a Twitter-sides data stream that Jesus doesn’t want you personally to be a tweet-sized follower of Jesus. You should put down the proverbial net – or in this case, the actual mouse and KB, or your laptop, or your phone or iPhone – and follow Jesus.

ntinomianism is one of those theological terms that is notoriously hard to pin down. It has an admittedly sinister sound, and when many people hear the term, they think it speaks of wantonly advocating sin ("Why not do evil that good may come?"—Romans 3:8). Indeed that kind of extreme antinomianism exists. It was the doctrine of

ntinomianism is one of those theological terms that is notoriously hard to pin down. It has an admittedly sinister sound, and when many people hear the term, they think it speaks of wantonly advocating sin ("Why not do evil that good may come?"—Romans 3:8). Indeed that kind of extreme antinomianism exists. It was the doctrine of

that they desire to obey God, there are two ways in which they still profit in the Law. For it is the best instrument for enabling them daily to learn with greater truth and certainty what that will of the Lord is which they aspire to follow, and to confirm them in this knowledge; just as a servant who desires with all his soul to approve himself to his master, must still observe, and be careful to ascertain his master's dispositions, that he may comport himself in accommodation to them. Let none of us deem ourselves exempt from this necessity, for none have as yet attained to such a degree of wisdom, as that they may not, by the daily instruction of the Law, advance to a purer knowledge of the Divine will. Then, because we need not doctrine merely, but exhortation also, the servant of God will derive this further advantage from the Law: by frequently meditating upon it, he will be excited to obedience, and confirmed in it, and so drawn away from the slippery paths of sin. In this way must the saints press onward . . .

that they desire to obey God, there are two ways in which they still profit in the Law. For it is the best instrument for enabling them daily to learn with greater truth and certainty what that will of the Lord is which they aspire to follow, and to confirm them in this knowledge; just as a servant who desires with all his soul to approve himself to his master, must still observe, and be careful to ascertain his master's dispositions, that he may comport himself in accommodation to them. Let none of us deem ourselves exempt from this necessity, for none have as yet attained to such a degree of wisdom, as that they may not, by the daily instruction of the Law, advance to a purer knowledge of the Divine will. Then, because we need not doctrine merely, but exhortation also, the servant of God will derive this further advantage from the Law: by frequently meditating upon it, he will be excited to obedience, and confirmed in it, and so drawn away from the slippery paths of sin. In this way must the saints press onward . . .

hy did not God ordain worship by windmills as in Thibet? Why has he not chosen to be worshipped by particular men in purple and fine linen, acting gracefully as in Roman and Anglican churches? Why not?

hy did not God ordain worship by windmills as in Thibet? Why has he not chosen to be worshipped by particular men in purple and fine linen, acting gracefully as in Roman and Anglican churches? Why not?

ack in the 1990s, I was an active participant in several e-mail forums devoted to theological discussion. I especially loved a couple of open forums where lay people, pastors, and seminary professors mingled—much like the combox of our blog. It was a helpful exercise in learning how to frame difficult concepts in simple terms. I loved the rookie participants, because they were full of good questions, eager to learn, and not afraid to challenge anything that seemed unclear or unbiblical.

ack in the 1990s, I was an active participant in several e-mail forums devoted to theological discussion. I especially loved a couple of open forums where lay people, pastors, and seminary professors mingled—much like the combox of our blog. It was a helpful exercise in learning how to frame difficult concepts in simple terms. I loved the rookie participants, because they were full of good questions, eager to learn, and not afraid to challenge anything that seemed unclear or unbiblical. But there were always a few lay participants who seemed to come to every discussion with the attitude that theology is (or ought to be) a dialectical exercise done mostly for recreation. They evidently thought the tools of the sport are nothing more than one's personal feelings, speculations, and inventiveness. Discussing doctrine was purely a diversion for them; nothing serious. But it seemed the more serious the topic under discussion, the more eagerly they jumped into the fray with their frivolous and half-baked ideas.

But there were always a few lay participants who seemed to come to every discussion with the attitude that theology is (or ought to be) a dialectical exercise done mostly for recreation. They evidently thought the tools of the sport are nothing more than one's personal feelings, speculations, and inventiveness. Discussing doctrine was purely a diversion for them; nothing serious. But it seemed the more serious the topic under discussion, the more eagerly they jumped into the fray with their frivolous and half-baked ideas.

The best way to ensure, by the providence of God, that I will have a full week at work is to promise to post something controversial which will require significant moderation and a lot of time disambiguating people regarding their own bum preconceptions.

The best way to ensure, by the providence of God, that I will have a full week at work is to promise to post something controversial which will require significant moderation and a lot of time disambiguating people regarding their own bum preconceptions.

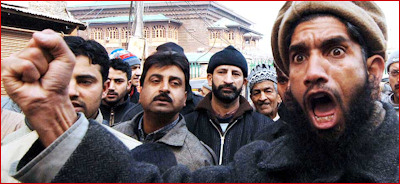

That's a thought to ponder if you want to fire up your vitriol in the comments -- in fact I insist: why do all the nut-jobs hate Calvinism most of all rather than, for example, the idea that God is the Eucharist, or that your soul will suffer in purgatory for your sin before you get to spend eternity with God and the Virgin Mary? Why is Calvinism the one they know they have to overcome?

That's a thought to ponder if you want to fire up your vitriol in the comments -- in fact I insist: why do all the nut-jobs hate Calvinism most of all rather than, for example, the idea that God is the Eucharist, or that your soul will suffer in purgatory for your sin before you get to spend eternity with God and the Virgin Mary? Why is Calvinism the one they know they have to overcome?

Wow! Like DOUBLE the number of sites! Seriously -- if the problem is that there's quite a lot of venom going around, check the internet, because clearly someone out there is wrong.

Wow! Like DOUBLE the number of sites! Seriously -- if the problem is that there's quite a lot of venom going around, check the internet, because clearly someone out there is wrong.