Click HERE to listen to this sermon excerpt from D. Martyn LLoyd-Jones.

hat was the sort of preaching you had from the Protestant Reformers. What kind of preaching? Prophetic preaching, not priestly preaching. What we have today, you know, is what I would call "priestly preaching"—very nice, very quiet, very beautiful, very ornate. Sentences turned beautifully; prepared carefully.

hat was the sort of preaching you had from the Protestant Reformers. What kind of preaching? Prophetic preaching, not priestly preaching. What we have today, you know, is what I would call "priestly preaching"—very nice, very quiet, very beautiful, very ornate. Sentences turned beautifully; prepared carefully.

That's not prophetic preaching. No, no! What is needed is authority!

Do you think that John Knox could make Mary Queen of Scots tremble with some polished little essay? These men didn't write their sermons with an eye to publication in books. They were preaching to the congregation in front of them. They were anxious and desirous to do something, to effect something, to change people. It was authoritative. What was it? It was proclamation. It was declaration.

Is it surprising that the church is that she is today? We don't believe in preaching any longer, do we? You used to have long sermons here in Scotland. I'm told you don't like them now, and woe be unto the preacher that goes on beyond 20 minutes.

I was reading coming up in the train yesterday about the first principal of Emmanuel College in Cambridge. He lived just at the end of the 16th century. His name was Chatterton. He was preaching on one occasion, and after he preached for two hours, he stopped, and he apologized to the people. He said, "Please, forgive me. I've got beyond myself. I mustn't go on like this."

And the congregation shouted out, "For God's sake, go on!"

You know, I'm beginning to think that I shan't have preached until something like that happens to me. Prophetic, authoritative, proclamation, declaration. A preaching that didn't respect persons, that wasn't anxious to play to the gallery, or to the intellectuals wherever they may sit. And certainly not our modern idea of having a friendly discussion. Have you noticed it? Less and less preaching on the wireless programs. Discussions! "Let the young people say what they think."

How interesting! Let's win them by letting them speak, and we'll have a friendly chat and discussion. We'll show them that, after all, we are nice, decent fellows, there's nothing nasty about us, and we'll gain their confidence. They mustn't think that we're unlike them. So of course, if you're on the television, you start by producing your pipe and lighting it. You show you're like the people—one of them.

Was John Knox like one of the people? Was John Knox, a matey? Friendly? Nice chap you can have a discussion with?

Thank God he wasn't. Scotland would not be what she has been for four centuries if John Knox were that kind of man.

And can you imagine John Knox going to have tips and training as to how he should conduct and comport himself before the television cameras? To be nice and polite and friendly and gentlemanly? Thank God prophets are made of sterner stuff.

And Amos. Or Jeremiah. Or John the Baptist in the wilderness—camel hair shirt. A strange fellow. "A lunatic," they said. "He's mad!" And they went and listened to him because he was a curiosity. And there, as they listened, they were convicted.

Such a man was John Knox, with the fire of God in his bones and in his belly. And he preached as they all preached—with fire, and power. Alarming sermons; convicting sermons; humbling sermons; converting sermons. And the face of Scotland was changed. And your greatest epoch in your long history came to pass. There, as I see it, were the great and outstanding characteristics of these men.

What was the secret of it all?

Well, it wasn't the men, as I've been trying to say, great as they were. It was God. God in his sovereignty, raising his men, and God knows what he's doing. Look at the gifts he gave John Knox as a natural men. Look at the mind he gave to Calvin. Look at the training he gave to Calvin as a lawyer to prepare him for his great work. Look at Martin Luther, that volcano of a man. God, preparing his men in the different nations and in the different countries.

And of course, before he even produced them, he'd been preparing the way for them. Let's never forget Wycliffe—John Wycliffe. John Hus. Let's never forget the Waldensians and all the martyrs of those terrible Middle Ages. God was preparing the way, and then he sent his men at the right moment. And the mighty events followed.

. . . . . . . .

The God of John Knox is still there, and still the same. And thank God, Jesus Christ is the same yesterday, today and forever.

Oh, that we might know the God of John Knox.

|

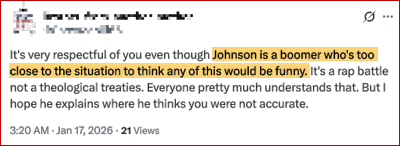

I'm often surprised and not a little shocked by the tone and flavor of some of the discourse on social media among people who self-identify as gospel-believing Christians. I'm not talking only about the annoying busybodies, false accusers, trash-talkers, and all-purpose haters. I'm thinking also of the people who routinely sprinkle their comments with obscene or profane language ("cuss words," as the idiom used to be known). They tend to be fiercely resistant to any criticism or correction of the practice. They think the casual use of salty language shows how "genuine," and "relatable" they are, and this somehow enhances the believability of their testimony.

I'm often surprised and not a little shocked by the tone and flavor of some of the discourse on social media among people who self-identify as gospel-believing Christians. I'm not talking only about the annoying busybodies, false accusers, trash-talkers, and all-purpose haters. I'm thinking also of the people who routinely sprinkle their comments with obscene or profane language ("cuss words," as the idiom used to be known). They tend to be fiercely resistant to any criticism or correction of the practice. They think the casual use of salty language shows how "genuine," and "relatable" they are, and this somehow enhances the believability of their testimony.

he followers of the early Reformers were distinguished by the sanctity of their lives. When they were about to hunt out the Waldenses, the French king, who had some of them in his dominions, sent a priest to see what they were like, and he, honest man as he was, came back to the king, and said, "As far as I could find, they seem to be much better Christians than we are. I am afraid they are heretics, but really they are so chaste, so honest, so upright, and so truly pious, that, though I hate heresy—I hope your majesty does not suspect me on that account—yet I would that all Catholics were as good as they are."

he followers of the early Reformers were distinguished by the sanctity of their lives. When they were about to hunt out the Waldenses, the French king, who had some of them in his dominions, sent a priest to see what they were like, and he, honest man as he was, came back to the king, and said, "As far as I could find, they seem to be much better Christians than we are. I am afraid they are heretics, but really they are so chaste, so honest, so upright, and so truly pious, that, though I hate heresy—I hope your majesty does not suspect me on that account—yet I would that all Catholics were as good as they are."

hen an enterprise begins in martyrdom, it is none the less likely to succeed; but when conquerors begin to preach the gospel to those they have conquered, it will not succeed; God will teach us that it is not by might.

hen an enterprise begins in martyrdom, it is none the less likely to succeed; but when conquerors begin to preach the gospel to those they have conquered, it will not succeed; God will teach us that it is not by might.

obody wonders that Mahometanism spread. After the Arab prophet had for a little while himself personally borne the brunt of persecution, he gathered to his side certain brave spirits who were ready to fight for him at all odds. You marvel not that the sharp arguments of scimitars made many converts.

obody wonders that Mahometanism spread. After the Arab prophet had for a little while himself personally borne the brunt of persecution, he gathered to his side certain brave spirits who were ready to fight for him at all odds. You marvel not that the sharp arguments of scimitars made many converts. Now, if our Lord had arranged a religion of fine shows, and pompous ceremonies, and gorgeous architecture, and enchanting music, and bewitching incense, and the like, we could have comprehended its growth; but he is "a root out of a dry ground," for he owes nothing to any of these. Christianity has been infinitely hindered by the musical, the æsthetic, and the ceremonial devices of men, but it has never been advantaged by them, no, not a jot. The sensuous delights of sound and sight have always been enlisted on the side of error, but Christ has employed nobler and more spiritual agencies.

Now, if our Lord had arranged a religion of fine shows, and pompous ceremonies, and gorgeous architecture, and enchanting music, and bewitching incense, and the like, we could have comprehended its growth; but he is "a root out of a dry ground," for he owes nothing to any of these. Christianity has been infinitely hindered by the musical, the æsthetic, and the ceremonial devices of men, but it has never been advantaged by them, no, not a jot. The sensuous delights of sound and sight have always been enlisted on the side of error, but Christ has employed nobler and more spiritual agencies.

ouTube and social media are full of AI-produced videos using John MacArthur's voice and image, making him say things that perhaps sound like something you might think he believed, but expressing opinions he never held and making statements he never made. There are dozens of these fake videos floating around, and I am asked about them almost daily.

ouTube and social media are full of AI-produced videos using John MacArthur's voice and image, making him say things that perhaps sound like something you might think he believed, but expressing opinions he never held and making statements he never made. There are dozens of these fake videos floating around, and I am asked about them almost daily. My standard reply: "No, those are fake. If you want to be certain you are hearing something John MacArthur actually said; or if you are looking for a video or audio recording of John's that you can trust to be genuine, you'll find it at

My standard reply: "No, those are fake. If you want to be certain you are hearing something John MacArthur actually said; or if you are looking for a video or audio recording of John's that you can trust to be genuine, you'll find it at  John was never a fan of Siri or Alexa, and he certainly did not want to lend his face, voice, or personality to an AI-generated cyber-pastor or digital rabbi. The idea of an artificial John MacArthur saying fake prayers for people with real needs absolutely appalled him—perhaps even more than it appalled the rest of us.

John was never a fan of Siri or Alexa, and he certainly did not want to lend his face, voice, or personality to an AI-generated cyber-pastor or digital rabbi. The idea of an artificial John MacArthur saying fake prayers for people with real needs absolutely appalled him—perhaps even more than it appalled the rest of us.

he power and grace of God will be conspicuously seen in the subjugation of this world to Christ: every heart shall know that it was wrought by the power of God in answer to the prayer of Christ and his church. I believe, brethren, that the length of time spent in the accomplishment of the divine plan has much of it been occupied with getting rid of those many forms of human power which have intruded into the place of the Spirit.

he power and grace of God will be conspicuously seen in the subjugation of this world to Christ: every heart shall know that it was wrought by the power of God in answer to the prayer of Christ and his church. I believe, brethren, that the length of time spent in the accomplishment of the divine plan has much of it been occupied with getting rid of those many forms of human power which have intruded into the place of the Spirit. If you and I had been about in our Lord’s day, and could have had everything managed to our hand, we should have converted Cæsar straight away by argument or by oratory; we should then have converted all his legions by every means within our reach; and, I warrant you, with Cæsar and his legions at our back we would have Christianised the world in no time: would we not? Yes, but that is not God’s way at all, nor the right and effectual way to set up a spiritual kingdom. Bribes and threats are alike unlawful, eloquence and carnal reasoning are out of court, the power of divine love is the one weapon for this campaign.

If you and I had been about in our Lord’s day, and could have had everything managed to our hand, we should have converted Cæsar straight away by argument or by oratory; we should then have converted all his legions by every means within our reach; and, I warrant you, with Cæsar and his legions at our back we would have Christianised the world in no time: would we not? Yes, but that is not God’s way at all, nor the right and effectual way to set up a spiritual kingdom. Bribes and threats are alike unlawful, eloquence and carnal reasoning are out of court, the power of divine love is the one weapon for this campaign.

hen Mahomed would spread his religion, he bade his disciples arm themselves, and then go and cry aloud in every street, and offer to men the alternative to become believers in the prophet, or to die. Mahomed's was a mighty voice, which spake with the edge of the scimitar. He delighted to quench the smoking flax, and break the bruised reed; but the religion of Jesus has advanced upon quite a different plan.

hen Mahomed would spread his religion, he bade his disciples arm themselves, and then go and cry aloud in every street, and offer to men the alternative to become believers in the prophet, or to die. Mahomed's was a mighty voice, which spake with the edge of the scimitar. He delighted to quench the smoking flax, and break the bruised reed; but the religion of Jesus has advanced upon quite a different plan.