by Phil Johnson

ithin the militantly Arminian sector of the Southern Baptist Convention, it seems there are still those who

insist that "by the definition of Phil Johnson," James White is a hyper-Calvinist.

That charge was made earlier this month by Dr. David Allen at the

"John 3:16 Conference" in Woodstock, GA. I first read about it a day later from a couple of live-bloggers who were present at that conference—

Andrew Lindsey and

the blogger known as johnMark. I commented on Dr. Allen's accusation immediately—first at Challies.com, then

here on the blog. James White also responded to Dr. Allen both

on his blog and

via his webcast.

I figured that would be the end of the matter. Evidently not.

My initial response to Dr. Allen was admittedly written very quickly. (After all, it was a comment on Tim Challies' blog, not a doctoral dissertation.) Reading it more than a week later, however, it still seems clear enough, and I stand by everything I said. The gist of it was that

if Dr. Allen thinks James White is a hyper-Calvinist by my definition, then he doesn't understand my definition.

Dr. Allen has now responded to his "critics." I can't tell whether he includes me in that category. I hope not, because classifying me as a "critic" makes it sound as if

I'm the one on the offense. For the record, that is not the case. I would never have replied to Dr. Allen's lecture at all if he had not misused and misquoted my

"Primer on Hyper-Calvinism" in a way that seemed calculated to pit me publicly against a friend.

Evidently, Dr. Allen isn't buying my explanation of my own position. He has a totally different interpretation of my notes on hyper-Calvinism, and he says he's going to "wait to see what Phil Johnson says"

after I read

his exegesis of my words. For those who have wondered: No, he didn't actually write me with any questions before undertaking to explain my views—or afterward, for that matter. Unless he used a pseudonym, he didn't comment on my blogpost

here, either. (That would probably have been the best place to interact with me about the issue if he had been so inclined.) But I've heard nothing from him directly. If a friend had not pointed out that Dr. Allen had posted that response on another blog, I would have had no way of knowing that he is "wait[ing]" to hear from me at all. So I gather he is not exactly waiting with bated breath.

Nevertheless, Dr. Allen's "defense" demonstrates conclusively that

he doesn't understand my definition of hyper-Calvinism. He relentlessly ascribes to me a position I have frequently refuted. He insists on paraphrasing my opinion in precisely the kind of ambiguous language I have emphatically repudiated. And (most frustrating of all) he utterly ignores everything I said in my earlier response to his lecture that might have helped shed light on the very things he misconstrues so badly.

For example, I made the point

on November 7 that contrary to what Dr. Allen claimed in his lecture,

my "Primer on hyper-Calvinism" deliberately says nothing whatsoever about God's "desires" with regard to the salvation of the reprobate. The use of such

optative terminology with respect to the divine decrees is notoriously problematic, because terms like

desire and

wish are usually loaded with Arminian freight. So I try

never to use such expressions without taking the time to explain what I mean. (Read carefully, for example,

footnote 20 in "God Without Mood Swings.")

Yet Dr. Allen continues to insist that by

my definition, one valid litmus test for hyper-Calvinism is a yes-or-no question about "God's universal saving will; namely, that God wills and desires to save the non-elect."

Before I point out how thoroughly wrong that idea is, let me also note that the fellow who provided blog space for Dr. Allen's "Defense"

insinuates that my earlier reply to Dr. Allen's remarks was based on a false report: "Johnson apparently has only responded to what was 'live-blogged' which is virtually limited to 'James White is a hyper-Calvinist according to Phil Johnson's definition.' I have not seen anything from Phil Johnson—or James White, for that matter—that comes close to dealing with what Dr. Allen actually presented at the J316C." (The fellow

elsewhere wrote a whole post blaming the livebloggers' "mistakes" for most of the controversy generated in the wake of the "John 3:16 Conference." But I've been listening to recordings of the messages today, and in my assessment, the actual conference was ten times more of a travesty than I gathered from reading the livebloggers' reports.)

In light of all that; since people are still talking about this; and since Dr. Allen is apparently waiting to hear from me, here are my further thoughts on Dr. Allen's original remarks and his more recent defense (including his blog-host's comments):

Regarding the supposed misrepresentation by livebloggers

First, let me say that I am utterly mystified by the suggestion that my earlier reply to Dr. Allen's comments was based on misinformation I got from people who blogged about the conference.

My post began by citing Andrew Lindsey, who wrote:

"Dr. Allen asserted that Dr. James White is a hyper-Calvinist according to Phil Johnson’s primer on hyper-Calvinism, as Dr. White says that God does not have any desire to save the non-elect." Now, if a secondhand source like that proved to be wrong, I would indeed owe Dr. Allen an apology. But the other liveblogger there was

johnMark, whose account said, "James White is a hyper-Calvinist by the definition of Phil Johnson. Oct. 10 on the Dividing Line White denied God wills the salvation of all men which is against Tom Ascol."

By the mouth of two independent witnesses, we had agreeing accounts.

I realize, of course, that while two eyewitness accounts might satisfy the biblical standard of evidence for capital crimes (Deuteronomy 17:6), they don't necessarily constitute infallible proof. So after reading Dr. Allen's "Defense," I listened to his complete "John 3:16" message for myself. (He sounds almost exactly like Jeff Foxworthy; hence the title of this post.) Not only am I very impressed with the accuracy and objectivity of the livebloggers' summaries, I have to say that the excerpts Dr. Allen himself quoted from his own message are

worse, not better, than the summaries I had previously read. The full recording is worse yet.

Here are his exact words regarding me and James White: "Ladies and Gentlemen,

James White is a hyper-Calvinist. By the definition of Phil Johnson in his A Primer of Hyper-Calvinism, Phil Johnson [founder] of spurgeon.org, who is the right hand man of John MacArthur,

Phil Johnson tells you the five things that make for hyper-Calvinism, and James White by his teaching is a hyper-Calvinist."

Notice the ambiguity of the clause after that final comma, and the double ambiguity of the prepositional phrase "by his teaching." Who is the antecedent of the pronoun there? Is Allen saying that James White's teaching makes him a hyper-Calvinist, or that my teaching declares him to be so? And is he saying Phil Johnson "tells you . . . James White is a hyper-Calvinist"? Surely not, because that would be a complete lie.

Nevertheless, I would be interested in knowing how anyone could possibly think the livebloggers portrayed Dr. Allen's remarks as something worse than they really are, because I frankly felt his actual remarks were a far worse misrepresentation of my opinion than I was led to believe merely from the blog summaries.

Regarding my definition of hyper-Calvinism

Remember: in my notes on hyper-Calvinism I

purposely avoided the use of optative expressions. The "Primer" was a short article (published in 2002 in

Sword and Trowel, from London's Metropolitan Tabernacle), and I simply did not have space to delve into the difficulties such language presents. Besides, optative language is inherently ambiguous and usually loaded with Arminian freight. Ultimately, the question of whether and in what sense God "desires" the repentance of the reprobate is important, but declining to use such language does not

ipso facto make someone a hyper-Calvinist. More important, the use or non-use of such expressions in the totally-unqualified way Dr. Allen insists on using them is far from the pivotal issue between historic Calvinists and hypers. In fact, his notion of "God’s universal saving will" sounds indistinguishable from Arminianism. (Is he suggesting that if you're not Arminian in your understanding of God's saving purpose, then you are a hyper-Calvinist? It sure sounds like that.) Someone of his stature and position really

ought to fulminate less and define and qualify terms more.

I thought my November 7 response to Dr. Allen's comments already said or implied

all those things. (I know I linked to a place where I had dealt more carefully with the problem of attributing unfulfilled "desires" to God.) For him to continue paraphrasing my position in terms I have expressly, emphatically, and repeatedly rejected makes a joke of his own claim (early in his lecture) that he is determined not to misrepresent any Calvinist whom he quotes. Moreover, his insistence on restating "my" position in his own terms (which I emphatically reject) runs counter to his own professed preference for "original sources."

Dr. Allen suggests that according to me, the essence of hyper-Calvinism is a denial of

"God’s universal saving will; namely, that God wills and desires to save the non-elect." But

none of the expressions he employs in that assertion are mine. Nor would I ever use or endorse unqualified language like that. Nor is that a close paraphrase of anything I

did say.

The only biblical expressions of God's "desire" with respect to the salvation of the reprobate is His command regarding what

they should do: "he commands all people everywhere to repent" (Acts 17:30). He has "no pleasure in the death of the wicked, but that the wicked turn from his way and live" (Ezekiel 33:11, etc.). Those texts speak of His preceptive will—His will with regard to what

they should do.

God's decretive will—His intention with regard to what

He Himself will do—is normally kept secret from us until His will is accomplished, but it is this aspect of His will that He refers to when He says, "My counsel shall stand, and I will accomplish

all my purpose" (Isaiah 46:10).

The distinction between the two aspects of the divine will is vital to historic Calvinism. It is dealt with thoroughly by John Piper

here. (My "Primer" contains a link to that article.)

Regarding Dr. Allen's definition of hyper-Calvinism

Every word of the expression "universal saving will" is problematic, particularly when Dr. Allen's only explanation of that idea is the phrase "namely, that God wills and desires to save the non-elect."

The word

universal with no qualifying terms or explanation suggests that God has no specific intention to save one sinner as opposed to another. Presumably the term suggests that God's ultimate purpose with regard to all sinners is

universally the same. So the question of who is saved is decided solely by the individual wills of sinners rather than the eternal purpose of God. That, of course, is precisely what Arminianism suggests, and absent any teaching to the contrary, I wonder if that is indeed the idea that Dr. Allen intends to convey. If so, he ought to say so clearly. If not, he needs to stop using the expression, or explain it better.

The word

saving suggests that God's

only sovereign purpose in the preaching of the gospel is salvation, and thus either His purpose will be thwarted, or all men will be saved. Either view is deplorable doctrine.

In a context like this, the word

will must be disambiguated. Dr. Allen clearly knows about the classic Calvinist distinctions. Whether he

understands them is unclear, because he never bothers to explain how he is using the word

will in this expression. Is this a reference to the decretive will of God (his secret, eternal purpose, which He Himself will bring to pass without fail), or His preceptive will (His will with regard to what He commands sinners to do)? In my assessment, much of Dr. Allen's critique of James White hinges on equivocation between the two senses of that word.

And what, precisely, is the purpose of Allen's insistence on putting so much stress on the idea of God's

"desire to save the non-elect"—without any comment on the problem of how optative terminology like that can properly apply to a God who is immutable, impassible, and sovereign; and without noting how infrequently such expressions are used in Scripture? Is he purposely trying to portray God as eternally frustrated by unfulfilled longings? Or does he recognize that those terms are anthropopathisms suited to our humanness but imperfect in their ability to explain the affections of God?

Dr. Allen never grapples with nor mentions any of those questions about the ambiguity of his key expression. That glaring omission makes it impossible to take his critique of Calvinism very seriously.

Regarding the sincerity of God's proposal of mercy in the gospel

Dr. Allen seems to build much of his case on my use of the word

sincere. I use that word in the formal, straightforward sense of "not feigned or pretended."

He raises this question about my position: "Is he or is he not saying that a 'sincere proposal' by God to all necessarily presupposes his willingness to save all, such that a denial of God's desire to save all is the same as denying the well-meant nature of the offer?" First, I don't see how "willingness" necessarily implies "desire." I'm

willing to get up early tomorrow morning if circumstances make it necessary; I am even

prepared to do so. But as it is a holiday, I

desire to sleep in. This notion that if God's

offer is "sincere" it must be the exact equivalent of what we think of humanly as a "desire" is a classic case of Dr. Allen's equivocation.

I've said repeatedly that I'm convinced God's pleas for the reprobate to repent are well-meant. Those beseechings are not (as some sterner Calvinists often suggest) feigned entreaties designed only to increase the damnation of those whom God only hates. I believe God has a genuine love for the non-elect because they are His creatures, made in His image. But it is not the

same love He has for the elect.

If Dr. Allen recognized those distinctions, he might be in a position to criticize high-Calvinist opinions meaningfully. As it is, his critique sounds like the classic Arminian misrepresentation:

"Everyone more calvinistic than I am is hyper."

Regarding various personal connections I have to this debate

Dr. Allen cited David Ponter as a source for some of his material. I've known Mr. Ponter since the mid 1990s, when he himself belonged to a hyper-Calvinist denomination. He has gradually moved toward the opposite end of the spectrum of Calvinist belief. Meanwhile, he has compiled an impressive collection of material (mostly quotations from early Calvinistic source material) arguing that historic mainstream Calvinism was of a milder flavor than the style of Calvinism that currently dominates most Internet discussions.

David's archives contain some excellent stuff, but it is definitely a very one-sided perspective. It is sometimes cited (and David is named) by Arminians and self-styled four-pointers who don't represent low Calvinism very well. David has lately tried very hard to keep his name out of debates like this. But since Dr. Allen cited him by name, I thought I would acknowledge his work and note that I don't necessarily fault him for every rhetorical and polemical faux pas made by people who gobble up his resources.

Curt Daniel, whose works are often cited favorably by "four-point Calvinists" and other types of Arminians, is likewise a friend of mine. He is perhaps the world's foremost authority on hyper-Calvinism, and no one who has not read Dr. Daniel's massive dissertation on John Gill should pretend to be well-informed on the history of hyper-Calvinism. Dr. Daniel might also hold to a milder sort of Calvinism than I do, but he is not the type who automatically labels every Calvinist who disagrees with him "hyper."

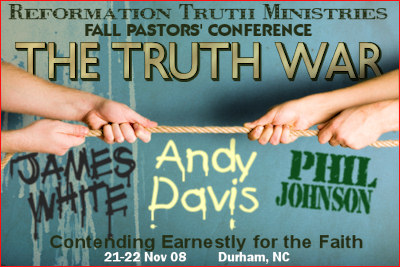

Regarding James White, he has been my friend longest of these three—dating back at least to the early 1990s. We did a conference together last week and did not get an opportunity to discuss Dr. Allen's lecture. If I had known the issue was going to resurface this week, I would have tried hard to make time for that discussion.

There may be points on which James White and I would differ on how to explain and defend Calvinism. He seems to be a higher sort of Calvinist than I am. That doesn't make him "hyper."

My own convictions are thoroughly and unapologetically Calvinistic—but more in the vein of Iain Murray than Arthur Pink. If you've read Murray's biography of Pink, you will know what I mean.

I often find myself standing in the middle, urging low Calvinists not to be so quick to label their high brethren "hyper," and likewise urging high Calvinists not to be so quick to dismiss their low brethren as crypto-Arminians. From my position, it is absolutely clear that there are

many different hues of Calvinism; we are not a monolithic community.

Critics on all sides would do well to try harder to understand that. I rather suspect Dr. Allen would be somewhat perturbed if his Calvinist critics incessantly argued that

his view of a god with eternally unfulfilled longings is really nothing more than the doctrine of Open Theism.

That, in my opinion, would be the exact equivalent of Dr. Allen's claim that high Calvinism's reluctance to make blithe use of optative language to describe God's demeanor toward the reprobate is nothing but the distilled essence of hyper-Calvinism.

I think he better think it out again.

eloved, be stedfast. . . . Do not be as some are, of doubtful mind, who know nothing, and even dare to say that nothing can be known. To such the highest wisdom is to suspect the truth of everything they once knew, and to hang in doubt as to whether there are any fundamentals at all.

eloved, be stedfast. . . . Do not be as some are, of doubtful mind, who know nothing, and even dare to say that nothing can be known. To such the highest wisdom is to suspect the truth of everything they once knew, and to hang in doubt as to whether there are any fundamentals at all.

wo years ago, I wrote

wo years ago, I wrote

ithin the militantly Arminian sector of the Southern Baptist Convention, it seems there are still those who insist that "by the definition of Phil Johnson," James White is a hyper-Calvinist.

ithin the militantly Arminian sector of the Southern Baptist Convention, it seems there are still those who insist that "by the definition of Phil Johnson," James White is a hyper-Calvinist. My initial response to Dr. Allen was admittedly written very quickly. (After all, it was a comment on Tim Challies' blog, not a doctoral dissertation.) Reading it more than a week later, however, it still seems clear enough, and I stand by everything I said. The gist of it was that if Dr. Allen thinks James White is a hyper-Calvinist by my definition, then he doesn't understand my definition.

My initial response to Dr. Allen was admittedly written very quickly. (After all, it was a comment on Tim Challies' blog, not a doctoral dissertation.) Reading it more than a week later, however, it still seems clear enough, and I stand by everything I said. The gist of it was that if Dr. Allen thinks James White is a hyper-Calvinist by my definition, then he doesn't understand my definition. In light of all that; since people are still talking about this; and since Dr. Allen is apparently waiting to hear from me, here are my further thoughts on Dr. Allen's original remarks and his more recent defense (including his blog-host's comments):

In light of all that; since people are still talking about this; and since Dr. Allen is apparently waiting to hear from me, here are my further thoughts on Dr. Allen's original remarks and his more recent defense (including his blog-host's comments):

ew Age spirituality is fast-food religion perfectly suited for a postmodern culture like ours. It offers a quick-and-easy feeling of satisfaction with almost no real nourishment for the soul, while it contains additives and artificial ingredients that are actually harmful to true spiritual health. But you can still have it your way. There are no dogmas, few demands, no sense of self-denial, and little need for faith. This is a kind of anti-religion: a spiritually-oriented worldview for people with an intuitive sense of the sacred, but who are wary of organized religion.

ew Age spirituality is fast-food religion perfectly suited for a postmodern culture like ours. It offers a quick-and-easy feeling of satisfaction with almost no real nourishment for the soul, while it contains additives and artificial ingredients that are actually harmful to true spiritual health. But you can still have it your way. There are no dogmas, few demands, no sense of self-denial, and little need for faith. This is a kind of anti-religion: a spiritually-oriented worldview for people with an intuitive sense of the sacred, but who are wary of organized religion. Because of the diversity of belief among New Age enthusiasts and the amorphous nature of the New Age network, a formal, succinct definition of the New Age movement is well-nigh impossible. But it will nevertheless be helpful to begin with a simple thumbnail description of the phenomenon we are concerned with. Then in a series of follow-up posts, we'll look more closely at some of the major elements of this simple description in order to consider why the New Age movement ought to be a matter of concern for biblical Christians.

Because of the diversity of belief among New Age enthusiasts and the amorphous nature of the New Age network, a formal, succinct definition of the New Age movement is well-nigh impossible. But it will nevertheless be helpful to begin with a simple thumbnail description of the phenomenon we are concerned with. Then in a series of follow-up posts, we'll look more closely at some of the major elements of this simple description in order to consider why the New Age movement ought to be a matter of concern for biblical Christians.

id you ever notice the intolerance of God's religion? In olden times the heathen, who had different gods, all of them respected the gods of their neighbors.

id you ever notice the intolerance of God's religion? In olden times the heathen, who had different gods, all of them respected the gods of their neighbors.

by Frank Turk

by Frank Turk (that's the city which rejected Paul, unlike the Bereans), just like Ephesus. So "such as it is" is actually "such as God has given it to us".

(that's the city which rejected Paul, unlike the Bereans), just like Ephesus. So "such as it is" is actually "such as God has given it to us".

mong the many words (and concepts) that have been deconstructed and redefined for these postmodern times is the idea of honesty.

mong the many words (and concepts) that have been deconstructed and redefined for these postmodern times is the idea of honesty. One of the best-known and most creative of these is PostSecret, a blog where people make grunge-art post-card "confessions" of their deepest, darkest secrets. (I would link to it, but frankly many of the confessions are too smutty to get a link from here.) I find "PostSecret" deeply disturbing. I'm especially amazed and appalled that

One of the best-known and most creative of these is PostSecret, a blog where people make grunge-art post-card "confessions" of their deepest, darkest secrets. (I would link to it, but frankly many of the confessions are too smutty to get a link from here.) I find "PostSecret" deeply disturbing. I'm especially amazed and appalled that  eware of a religion without holdfasts. But if I get a grip upon a doctrine they call me a bigot. Let them do so. Bigotry is a hateful thing, and yet that which is now abused as bigotry is a great

eware of a religion without holdfasts. But if I get a grip upon a doctrine they call me a bigot. Let them do so. Bigotry is a hateful thing, and yet that which is now abused as bigotry is a great  virtue, and greatly needed in these frivolous times. I have been inclined lately to start a new denomination, and call it "the Church of the Bigoted."

virtue, and greatly needed in these frivolous times. I have been inclined lately to start a new denomination, and call it "the Church of the Bigoted."