I have read a book or two on Spurgeon that were more hagiographical than biographical. Even the terminology was glittery, gauzy, glistering and gagular.

Spurgeon's own remarks about himself were nothing of the kind.

Once I had nothing but a heart of stone, and although through grace I now have a new and fleshy heart, much of my former obduracy remains. I am not affected by the death of Jesus as I ought to be; neither am I moved by the ruin of my fellow men, the wickedness of the times, the chastisement of my heavenly Father, and my own failures, as I should be. O that my heart would melt at the recital of my Saviour’s sufferings and death. Would to God I were rid of this nether millstone within me, this hateful body of death. Blessed be the name of the Lord, the disease is not incurable, the Saviour’s precious blood is the universal solvent, and me, even me, it will effectually soften, till my heart melts as wax before the fire. (Charles H. Spurgeon, Morning and Evening : April 28 PM, emphases added)I confess that this deeply resonates with me. Spurgeon echoes laments and prayers of my own, as if he had eavesdropped on some (many) of my own pleas, supplications, and confessions.

And this is why I have kept coming to Spurgeon for something like three decades, now. I have known of a fine Bible teacher or two, perhaps accurate in their rehearsal of doctrine and interpretation, but whose confessions of imperfection (if they ever come) seem de rigeur and formal rather than heartfelt. Sermon illustrations are drawn from others' follies or frailties.

Spurgeon's confessions never, ever have that feel. They are clearly always heartfelt and genuine. Yet at the same time he

always avoids the opposite snare of that sort of self-indulgent transparency which betrays the generation of God's children (Psalm 73:15).

always avoids the opposite snare of that sort of self-indulgent transparency which betrays the generation of God's children (Psalm 73:15).For with these admissions, all the more do we read of Spurgeon's deep love for Christ, his unending and ever-fresh delight at the riches of God's covenant with His elect. As I've said, he's like a man amazed to find himself an heir, incredulously plunging his hands deeply into piles of gold coins again and again, letting them trickle out and ring back into the abundance. Only for Spurgeon the riches are far better than gold; they are the riches of Christ.

In this I think he rather reflects the Psalms that he loved (and I love) so much. We overhear both strains in the songs of Israel, often and poignantly.

If we hear the psalmists sing...

O LORD, rebuke me not in your anger,...or...

nor discipline me in your wrath.

2 Be gracious to me, O LORD, for I am languishing;

heal me, O LORD, for my bones are troubled.

3 My soul also is greatly troubled.

But you, O LORD--how long?

(Psalm 6:1-3)

For evils have encompassed me beyond number;...we can also overhear...

my iniquities have overtaken me, and I cannot see;

they are more than the hairs of my head;

my heart fails me

(Psalms 40:12)

You have put more joy in my heart...and...

than they have when their grain and wine abound.

(Psalm 4:7)

Then I will go to the altar of God, to God my exceeding joy,...and again...

and I will praise you with the lyre, O God, my God.

(Psalm 43:4)

Be glad in the LORD, and rejoice, O righteous,Spurgeon admits his neediness, but he does so that the reader may identify with him as he does

and shout for joy, all you upright in heart!

(Psalm 32:11)

so, and then immediately Spurgeon takes both himself and his reader to the Savior. Never does Spurgeon plead for pity; always does he speak so that the reader will hasten to the same Cross, the same grace, the same mercy, the same Savior, to whom Spurgeon himself keeps hastening with all his sorrows and needs and pain.

so, and then immediately Spurgeon takes both himself and his reader to the Savior. Never does Spurgeon plead for pity; always does he speak so that the reader will hasten to the same Cross, the same grace, the same mercy, the same Savior, to whom Spurgeon himself keeps hastening with all his sorrows and needs and pain.Spurgeon uses himself as James uses Elijah: "Elijah was a man with a nature like ours," he says. The KJV memorably renders ἄνθρωπος ἦν ὁμοιοπαθὴς ἡμῖν as "a man subject to like passions as we are." The BAGD lexicon explains the adjective as " pert. to experiencing similarity in feelings or circumstances, with the same nature."

And? What of it? James continues, "and he prayed fervently that it might not rain, and for three years and six months it did not rain on the earth" (James 5:17). We do not and must not look at Elijah (nor Spurgeon) and see a creature of different frame than we. They are of the same frame as we. Ah! but captivated by faith — what did God do through them! So, take heart, hope, trust, rise, do also.

"I know weakness and frailty and coldness, in myself, like you," Spurgeon says (in effect). "But I find all I need and more in Jesus Christ. I am poor in myself, I despair of myself; but that drives me to Him, and I rejoice in Him, and am rich in Him. We have the same nature, you and I, and we have the same Savior. Flee to Him, as I do, and find your sorrowing heart's deepest desire — as I have."

I know that Christ is perfect. But I also know I am not. What I need to know is: can such a miserably flawed man as I find hope, life, and joy in Christ?

Spurgeon tells us he knows for a personal fact that we can.

And his testimony has both the ring of authenticity, and the backing of Scripture.

I've been busy in the last week doing all manner of things, and we're still steeped in the first 5 verses of Paul's letter to Titus, but last week's post seems to have thrown a lot of people for a loop. I have tried to form up some private letters to answer some of the private questions asked, but I keep coming back to the same thing I started with last week -- at least internally.

I've been busy in the last week doing all manner of things, and we're still steeped in the first 5 verses of Paul's letter to Titus, but last week's post seems to have thrown a lot of people for a loop. I have tried to form up some private letters to answer some of the private questions asked, but I keep coming back to the same thing I started with last week -- at least internally. Isn't that who we ought to be? And that's merely those of us who are Christians in the broad sense. How much more should this be true of our pastors, in order that they might say, as Paul did, "

Isn't that who we ought to be? And that's merely those of us who are Christians in the broad sense. How much more should this be true of our pastors, in order that they might say, as Paul did, "

This is a continuation of the topic introduced

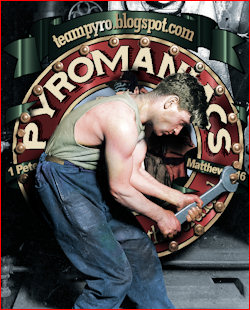

This is a continuation of the topic introduced  oday's evangelicals seem committed to keeping the church a soft, delicate, sissified environment. All the sharp corners are carefully filed down and rounded off every truth. Even the tone of the preacher has to be suited to the sewing circle—and qualities like sponginess and hesitancy have become a thousand times more common than accuracy and plain speaking. Evangelicals constantly say they want their leaders to be "vulnerable."

oday's evangelicals seem committed to keeping the church a soft, delicate, sissified environment. All the sharp corners are carefully filed down and rounded off every truth. Even the tone of the preacher has to be suited to the sewing circle—and qualities like sponginess and hesitancy have become a thousand times more common than accuracy and plain speaking. Evangelicals constantly say they want their leaders to be "vulnerable." It's worth pointing out the problem anyway. Coddle an effeminate disposition and it will get worse. And this could very well be the worst possible time in all of history for the church to go soft. It's not a problem we can afford to ignore politely.

It's worth pointing out the problem anyway. Coddle an effeminate disposition and it will get worse. And this could very well be the worst possible time in all of history for the church to go soft. It's not a problem we can afford to ignore politely.

e may be partakers in other men's sins by tempting them to sin. This is a most hateful thing, and makes the man who practices it to become the devil's most devoted drudge, servant, and slave.

e may be partakers in other men's sins by tempting them to sin. This is a most hateful thing, and makes the man who practices it to become the devil's most devoted drudge, servant, and slave.

ots of people are talking these days about the church's failure to reach men. The problem is an old one. To a large degree it is rooted in the eighteenth-century tendency of post-puritan preachers to temper hard truths and cushion the message as much as possible.

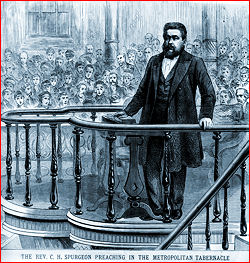

ots of people are talking these days about the church's failure to reach men. The problem is an old one. To a large degree it is rooted in the eighteenth-century tendency of post-puritan preachers to temper hard truths and cushion the message as much as possible. Charles Spurgeon abhorred that trend. He exemplified the opposite style. In fact, when Spurgeon first took his pastorate in London, one of the earliest caricatures published in the London newspapers about Spurgeon pictured him casting the shadow of a young lion from his pulpit—and it contrasted him with a typical Anglican clergyman, who cast the shadow of an old woman.

Charles Spurgeon abhorred that trend. He exemplified the opposite style. In fact, when Spurgeon first took his pastorate in London, one of the earliest caricatures published in the London newspapers about Spurgeon pictured him casting the shadow of a young lion from his pulpit—and it contrasted him with a typical Anglican clergyman, who cast the shadow of an old woman. Spurgeon was a man's preacher, and his ministry reflected that. He influenced men—and he is still influencing men from the grave. And even though he was criticized and despised and belittled in his own time for being too aggressive in his defense of the truth, notice that we still read Spurgeon, and his words are still absolutely relevant to our times. But everyone has utterly forgotten all the effeminate preachers of that era who at the time were absolutely certain that they were more "relevant" because they were more in tune with their own times than Spurgeon was.

Spurgeon was a man's preacher, and his ministry reflected that. He influenced men—and he is still influencing men from the grave. And even though he was criticized and despised and belittled in his own time for being too aggressive in his defense of the truth, notice that we still read Spurgeon, and his words are still absolutely relevant to our times. But everyone has utterly forgotten all the effeminate preachers of that era who at the time were absolutely certain that they were more "relevant" because they were more in tune with their own times than Spurgeon was.

ixteen years ago Crossway released John MacArthur's Ashamed of the Gospel. That book has never gone out of print. It was a critique of Willow Creek- and Saddleback-style quests for "relevance."

ixteen years ago Crossway released John MacArthur's Ashamed of the Gospel. That book has never gone out of print. It was a critique of Willow Creek- and Saddleback-style quests for "relevance." Things are different now. For one thing, virtually everything that seemed so breathtakingly fresh and relevant in the world of seeker-sensitivity sixteen years ago is now out of fashion. Some of it has even become fodder for post-evangelical scorn and mockery. Bill Hybels finally seems to have stopped talking about "unchurched Harry." Rick Warren has broadened his schtick and is trying hard to tie his name to some of Hollywood's pet political causes. (So much for "felt needs.") Other terms that were in vogue back then (like seeker-sensitive and user-friendly) aren't quite as popular today as they were sixteen years ago, either.

Things are different now. For one thing, virtually everything that seemed so breathtakingly fresh and relevant in the world of seeker-sensitivity sixteen years ago is now out of fashion. Some of it has even become fodder for post-evangelical scorn and mockery. Bill Hybels finally seems to have stopped talking about "unchurched Harry." Rick Warren has broadened his schtick and is trying hard to tie his name to some of Hollywood's pet political causes. (So much for "felt needs.") Other terms that were in vogue back then (like seeker-sensitive and user-friendly) aren't quite as popular today as they were sixteen years ago, either.

E live in very singular times just now. The professing Church has been flattering itself that, notwithstanding all our divisions with regard to doctrine, we are all right in the main. A false and spurious liberality has been growing up which has covered us all, so that we have dreamed that all who bore the name of ministers were indeed God's servants—that all who occupied pulpits, of whatever denomination they might be, were entitled to our respect, as being stewards of the mystery of Christ. But, lately, the weeds upon the surface of the stagnant pool have been a little stirred and we have been enabled to look down into the depths. This is a day of strife—a day of division—a time of war and fighting between professing Christians! God be thanked for it! Far better that it should be so than that the false calm shall any longer exert its fatal spell over us!

E live in very singular times just now. The professing Church has been flattering itself that, notwithstanding all our divisions with regard to doctrine, we are all right in the main. A false and spurious liberality has been growing up which has covered us all, so that we have dreamed that all who bore the name of ministers were indeed God's servants—that all who occupied pulpits, of whatever denomination they might be, were entitled to our respect, as being stewards of the mystery of Christ. But, lately, the weeds upon the surface of the stagnant pool have been a little stirred and we have been enabled to look down into the depths. This is a day of strife—a day of division—a time of war and fighting between professing Christians! God be thanked for it! Far better that it should be so than that the false calm shall any longer exert its fatal spell over us!

ecently I got an e-mail that raised an excellent, but difficult, question about apologetics. My correspondent was trying to make sense of the inevitable tension we face in those moments when we are called upon "to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you . . . with gentleness and respect"—and yet we know that the best biblical answer we have to someone's question or challenge is strongly counter cultural and possibly even offensive to the person we're speaking to.

ecently I got an e-mail that raised an excellent, but difficult, question about apologetics. My correspondent was trying to make sense of the inevitable tension we face in those moments when we are called upon "to make a defense to anyone who asks you for a reason for the hope that is in you . . . with gentleness and respect"—and yet we know that the best biblical answer we have to someone's question or challenge is strongly counter cultural and possibly even offensive to the person we're speaking to. I have no problem with the answer you gave. "Because they were an abomination to God" is a perfectly valid response: It's true, and it is, after all, the correct biblical answer to the question.

I have no problem with the answer you gave. "Because they were an abomination to God" is a perfectly valid response: It's true, and it is, after all, the correct biblical answer to the question.

You know: there is a perpetual merciless beating against pastors on the internet -- and I admit that some of them need it. But one of the things, dear pastor reader, that you must take to heart is that God really did intend that the local church have local pastors. That is, pastors and not vigilante theological or political brawlers. Or, if I may say it without stepping on too many toes, a face on a jumbotron. Men who are, well, like the next part of this passage who are frankly charged with the well-being of Christ's people for the sake of teaching them who Christ is, who He has made them, and what that means in their daily life.

You know: there is a perpetual merciless beating against pastors on the internet -- and I admit that some of them need it. But one of the things, dear pastor reader, that you must take to heart is that God really did intend that the local church have local pastors. That is, pastors and not vigilante theological or political brawlers. Or, if I may say it without stepping on too many toes, a face on a jumbotron. Men who are, well, like the next part of this passage who are frankly charged with the well-being of Christ's people for the sake of teaching them who Christ is, who He has made them, and what that means in their daily life.