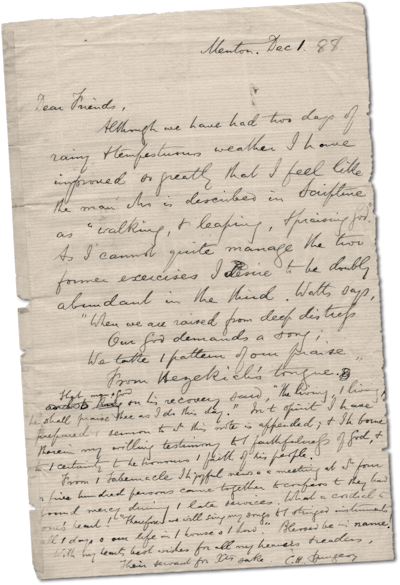

by Charles Spurgeon

posted by Phil Johnson

he power and grace of God will be conspicuously seen in the subjugation of this world to Christ: every heart shall know that it was wrought by the power of God in answer to the prayer of Christ and his church. I believe, brethren, that the length of time spent in the accomplishment of the divine plan has much of it been occupied with getting rid of those many forms of human power which have intruded into the place of the Spirit.

he power and grace of God will be conspicuously seen in the subjugation of this world to Christ: every heart shall know that it was wrought by the power of God in answer to the prayer of Christ and his church. I believe, brethren, that the length of time spent in the accomplishment of the divine plan has much of it been occupied with getting rid of those many forms of human power which have intruded into the place of the Spirit.

If you and I had been about in our Lord’s day, and could have had everything managed to our hand, we should have converted Cæsar straight away by argument or by oratory; we should then have converted all his legions by every means within our reach; and, I warrant you, with Cæsar and his legions at our back we would have Christianised the world in no time: would we not? Yes, but that is not God’s way at all, nor the right and effectual way to set up a spiritual kingdom. Bribes and threats are alike unlawful, eloquence and carnal reasoning are out of court, the power of divine love is the one weapon for this campaign.

If you and I had been about in our Lord’s day, and could have had everything managed to our hand, we should have converted Cæsar straight away by argument or by oratory; we should then have converted all his legions by every means within our reach; and, I warrant you, with Cæsar and his legions at our back we would have Christianised the world in no time: would we not? Yes, but that is not God’s way at all, nor the right and effectual way to set up a spiritual kingdom. Bribes and threats are alike unlawful, eloquence and carnal reasoning are out of court, the power of divine love is the one weapon for this campaign.

Long ago the prophet wrote, “Not by might, nor by power, but by my Spirit, saith the Lord.” The fact is that such conversions as could be brought about by physical force, or by mere mental energy, or by the prestige of rank and pomp, are not conversions at all. The kingdom of Christ is not a kingdom of this world, else would his servants fight; it rests on a spiritual basis, and is to be advanced by spiritual means. Yet Christ’s servants gradually slipped down into the notion that his kingdom was of this world, and could be upheld by human power.

A Roman emperor professed to be converted, using a deep policy to settle himself upon the throne; then Christianity became the State-patronized religion: it seemed that the world was Christianized, whereas, indeed, the church was heathenized. Hence sprang the monster of a State-church, a conjunction ill-assorted, and fraught with untold ills. This incongruous thing is half human, half divine: as a theory it fascinates, as a fact it betrays; it promises to advance the truth, and is itself a negation of it. Under its influences a system of religion was fashioned, which beyond all false religions, and beyond even Atheism itself, is the greatest hindrance to the true gospel of Jesus Christ. Under its influence dark ages lowered over the world; men were not permitted to think; a Bible could scarcely be found, and a preacher of the gospel, if found, was put to death.

| That was the result of human power coming in with the sword in one hand and the gospel in the other, and developing its pride of ecclesiastical power into a triple crown, an Inquisition, and an infallible Pope. This parasite, this canker, this incubus of the church will be removed by the grace of God. |

|

That was the result of human power coming in with the sword in one hand and the gospel in the other, and developing its pride of ecclesiastical power into a triple crown, an Inquisition, and an infallible Pope. This parasite, this canker, this incubus of the church will be removed by the grace of God, and by his providence in due season. The kings of the earth who have loved this unchaste system will grow weary of it and destroy it. Read Revelation 17:16, and see how terrible her end will be. The death of the system will come from those who gave it life: the powers of earth created the system, and they will in due time destroy it.

Frequently do we meet with the idea that the world is to be converted to Christ by the spread of civilization. Now, civilization always follows the gospel, and is in a great measure the product of it; but many people put the cart before the horse, and make civilization the first cause. According to their opinion trade is to regenerate the nations, the arts are to ennoble them, and education is to purify them. Peace Societies are formed, against which I have not a word to say, but much in their favour; still, I believe the only efficient peace society is the church of God, and the best peace teaching is the love of God in Christ Jesus. The grace of God is the great instrument for uplifting the world from the depths of its ruin, and covering it with happiness and holiness. Christ’s cross is the Pharos of this tempestuous sea, like the Eddystone lighthouse flinging its beams through the midnight of ignorance over the raging waters of human sin, preserving men from rock and shipwreck, piloting them into the port of peace.

Tell it out among the heathen that the Lord reigneth from the tree; and as ye tell it out believe that the power to make the peoples believe it is with God the Father, and the power to bow them before Christ is in God the Holy Ghost. Saving energy lies not in learning, nor in wit, nor in eloquence, nor in anything save in the right arm of God, who will be exalted among the heathen, for he hath sworn that surely all flesh shall see the salvation of God. The might of the Omnipotent One shall work out his purposes of grace, and as for us, we will use the simple processes of prayer and faith. “Ask of me, and I shall give thee.”

Oh, that we could keep in perpetual motion the machinery of prayer. Pray, pray, pray, and God will give, give, give, abundantly, and supernatnrally, above all that we ask, or even think. He must do all things in the conquering work of the Lord Jesus. We cannot convert a single child, nor bring to Christ the humblest peasant, nor lead to peace the most hopeful youth; all must be done by the Spirit of God alone, and if ever nations are to be born in a day, and crowds are to come humbly to Jesus’ feet, it is thine, Eternal Spirit, thine to do it. God must give the dominion, or the rebels will remain unsubdued.

Charles H. Spurgeon, "Christ’s Universal Kingdom, and How It Cometh," in The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit (London: Passmore & Alabaster, 1880), vol. 26, pp. 261–263.

he followers of the early Reformers were distinguished by the sanctity of their lives. When they were about to hunt out the Waldenses, the French king, who had some of them in his dominions, sent a priest to see what they were like, and he, honest man as he was, came back to the king, and said, "As far as I could find, they seem to be much better Christians than we are. I am afraid they are heretics, but really they are so chaste, so honest, so upright, and so truly pious, that, though I hate heresy—I hope your majesty does not suspect me on that account—yet I would that all Catholics were as good as they are."

he followers of the early Reformers were distinguished by the sanctity of their lives. When they were about to hunt out the Waldenses, the French king, who had some of them in his dominions, sent a priest to see what they were like, and he, honest man as he was, came back to the king, and said, "As far as I could find, they seem to be much better Christians than we are. I am afraid they are heretics, but really they are so chaste, so honest, so upright, and so truly pious, that, though I hate heresy—I hope your majesty does not suspect me on that account—yet I would that all Catholics were as good as they are."

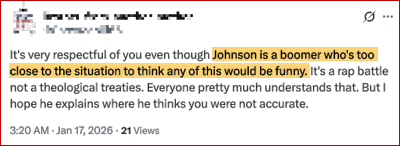

I'm often surprised and not a little shocked by the tone and flavor of some of the discourse on social media among people who self-identify as gospel-believing Christians. I'm not talking only about the annoying busybodies, false accusers, trash-talkers, and all-purpose haters. I'm thinking also of the people who routinely sprinkle their comments with obscene or profane language ("cuss words," as the idiom used to be known). They tend to be fiercely resistant to any criticism or correction of the practice. They think the casual use of salty language shows how "genuine," and "relatable" they are, and this somehow enhances the believability of their testimony.

I'm often surprised and not a little shocked by the tone and flavor of some of the discourse on social media among people who self-identify as gospel-believing Christians. I'm not talking only about the annoying busybodies, false accusers, trash-talkers, and all-purpose haters. I'm thinking also of the people who routinely sprinkle their comments with obscene or profane language ("cuss words," as the idiom used to be known). They tend to be fiercely resistant to any criticism or correction of the practice. They think the casual use of salty language shows how "genuine," and "relatable" they are, and this somehow enhances the believability of their testimony.

hen an enterprise begins in martyrdom, it is none the less likely to succeed; but when conquerors begin to preach the gospel to those they have conquered, it will not succeed; God will teach us that it is not by might.

hen an enterprise begins in martyrdom, it is none the less likely to succeed; but when conquerors begin to preach the gospel to those they have conquered, it will not succeed; God will teach us that it is not by might.

obody wonders that Mahometanism spread. After the Arab prophet had for a little while himself personally borne the brunt of persecution, he gathered to his side certain brave spirits who were ready to fight for him at all odds. You marvel not that the sharp arguments of scimitars made many converts.

obody wonders that Mahometanism spread. After the Arab prophet had for a little while himself personally borne the brunt of persecution, he gathered to his side certain brave spirits who were ready to fight for him at all odds. You marvel not that the sharp arguments of scimitars made many converts. Now, if our Lord had arranged a religion of fine shows, and pompous ceremonies, and gorgeous architecture, and enchanting music, and bewitching incense, and the like, we could have comprehended its growth; but he is "a root out of a dry ground," for he owes nothing to any of these. Christianity has been infinitely hindered by the musical, the æsthetic, and the ceremonial devices of men, but it has never been advantaged by them, no, not a jot. The sensuous delights of sound and sight have always been enlisted on the side of error, but Christ has employed nobler and more spiritual agencies.

Now, if our Lord had arranged a religion of fine shows, and pompous ceremonies, and gorgeous architecture, and enchanting music, and bewitching incense, and the like, we could have comprehended its growth; but he is "a root out of a dry ground," for he owes nothing to any of these. Christianity has been infinitely hindered by the musical, the æsthetic, and the ceremonial devices of men, but it has never been advantaged by them, no, not a jot. The sensuous delights of sound and sight have always been enlisted on the side of error, but Christ has employed nobler and more spiritual agencies.

ouTube and social media are full of AI-produced videos using John MacArthur's voice and image, making him say things that perhaps sound like something you might think he believed, but expressing opinions he never held and making statements he never made. There are dozens of these fake videos floating around, and I am asked about them almost daily.

ouTube and social media are full of AI-produced videos using John MacArthur's voice and image, making him say things that perhaps sound like something you might think he believed, but expressing opinions he never held and making statements he never made. There are dozens of these fake videos floating around, and I am asked about them almost daily. My standard reply: "No, those are fake. If you want to be certain you are hearing something John MacArthur actually said; or if you are looking for a video or audio recording of John's that you can trust to be genuine, you'll find it at

My standard reply: "No, those are fake. If you want to be certain you are hearing something John MacArthur actually said; or if you are looking for a video or audio recording of John's that you can trust to be genuine, you'll find it at  John was never a fan of Siri or Alexa, and he certainly did not want to lend his face, voice, or personality to an AI-generated cyber-pastor or digital rabbi. The idea of an artificial John MacArthur saying fake prayers for people with real needs absolutely appalled him—perhaps even more than it appalled the rest of us.

John was never a fan of Siri or Alexa, and he certainly did not want to lend his face, voice, or personality to an AI-generated cyber-pastor or digital rabbi. The idea of an artificial John MacArthur saying fake prayers for people with real needs absolutely appalled him—perhaps even more than it appalled the rest of us.

he power and grace of God will be conspicuously seen in the subjugation of this world to Christ: every heart shall know that it was wrought by the power of God in answer to the prayer of Christ and his church. I believe, brethren, that the length of time spent in the accomplishment of the divine plan has much of it been occupied with getting rid of those many forms of human power which have intruded into the place of the Spirit.

he power and grace of God will be conspicuously seen in the subjugation of this world to Christ: every heart shall know that it was wrought by the power of God in answer to the prayer of Christ and his church. I believe, brethren, that the length of time spent in the accomplishment of the divine plan has much of it been occupied with getting rid of those many forms of human power which have intruded into the place of the Spirit. If you and I had been about in our Lord’s day, and could have had everything managed to our hand, we should have converted Cæsar straight away by argument or by oratory; we should then have converted all his legions by every means within our reach; and, I warrant you, with Cæsar and his legions at our back we would have Christianised the world in no time: would we not? Yes, but that is not God’s way at all, nor the right and effectual way to set up a spiritual kingdom. Bribes and threats are alike unlawful, eloquence and carnal reasoning are out of court, the power of divine love is the one weapon for this campaign.

If you and I had been about in our Lord’s day, and could have had everything managed to our hand, we should have converted Cæsar straight away by argument or by oratory; we should then have converted all his legions by every means within our reach; and, I warrant you, with Cæsar and his legions at our back we would have Christianised the world in no time: would we not? Yes, but that is not God’s way at all, nor the right and effectual way to set up a spiritual kingdom. Bribes and threats are alike unlawful, eloquence and carnal reasoning are out of court, the power of divine love is the one weapon for this campaign.

hen Mahomed would spread his religion, he bade his disciples arm themselves, and then go and cry aloud in every street, and offer to men the alternative to become believers in the prophet, or to die. Mahomed's was a mighty voice, which spake with the edge of the scimitar. He delighted to quench the smoking flax, and break the bruised reed; but the religion of Jesus has advanced upon quite a different plan.

hen Mahomed would spread his religion, he bade his disciples arm themselves, and then go and cry aloud in every street, and offer to men the alternative to become believers in the prophet, or to die. Mahomed's was a mighty voice, which spake with the edge of the scimitar. He delighted to quench the smoking flax, and break the bruised reed; but the religion of Jesus has advanced upon quite a different plan.