Another in our slowly unfolding series on Acts 17

by Phil Johnson

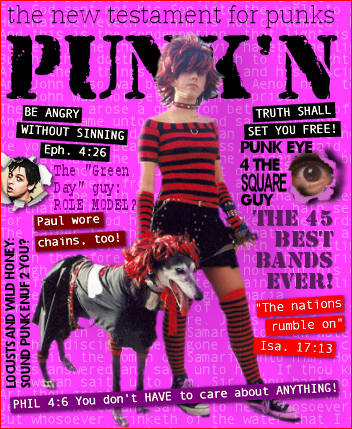

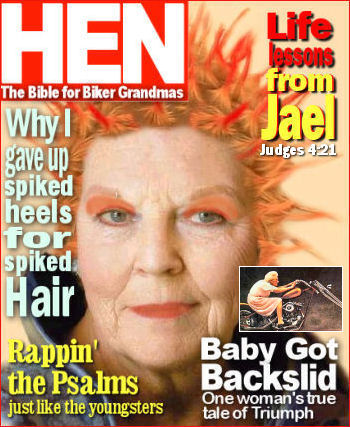

ead (and believe) enough of the trendy books and blogs that talk about missional living, and you'll get the distinct impression that fitting into this world's cultures is vastly more important—and a much more effective evangelistic strategy—than knowing the gospel message and communicating it with boldness, precision, and clarity.

What might Paul have thought of the missional fads of post-evangelicalism? Lots of people will argue that

Paul is the very model of a postmodern ministry strategist, and that Acts 17 is the classic narrative passage where we see his genius for cultural assimilation in all its perfect splendor.

Really? Let's see how that chapter actually unfolds. At the start of it (Acts 17:1-9), Paul's ministry in Thessalonica so offends the Jewish populace that their leaders deliberately stir up civil unrest. As a result, the apostle can no longer minister publicly in Thessalonica without the threat of a riot. So he goes to Berea under cover of night (v. 10).

Berea is about forty miles inland from Thessalonica and not on a major trade route, so the plan might have been to go to the closest place where Paul might preach the gospel without quite so much deliberate opposition from Jewish leaders in the region. But when he arrived in Berea, he didn't lay low and hide out or try to minister silently through lifestyle evangelism. He started proclaiming the gospel in the synagogue and the public square there, too.

However, Luke says, "when the Jews from Thessalonica learned that the Word of God was preached by Paul at Berea, they came there also and stirred up the crowds. Then immediately the brethren sent Paul away, to go to the sea; but both Silas and Timothy remained there" (v. 13). So Paul's missionary team spirited him away into hiding yet again. He was clearly

not winning general admiration and grass-roots popularity in the cultures where he was taking the gospel.

People kept trying to kill him.

Paul couldn't go back to Thessalonica or Berea now, because his enemies in those cities were determined to disrupt any ministry he did. So "those who conducted Paul brought him to Athens; and receiving a command for Silas and Timothy to come to him with all speed, they departed" (v. 15). Commentators generally assume he went by ship, because that seems the easiest, safest, and most reasonable way to travel from the coast near Berea to Athens.

Now, here's the scenario: Paul is cut off from his missionary team and sent to Athens for his own safety. From Berea and Thessalonica to Athens is about four days' travel by land and two or three days by sea (depending on the wind and the tides). So when Paul sends word back to Timothy and Silas to join him in Athens, he probably has about a two-week wait before they can join him there, and he spends that time alone in Athens, investigating the city and its culture. But he simultaneously launches his public ministry in Athens both at the synagogue there, and in the public square.

Now while Paul waited for them at Athens, his spirit was provoked within him when he saw that the city was given over to idols. Therefore he reasoned in the synagogue with the Jews and with the Gentile worshipers, and in the marketplace daily with those who happened to be there. Then certain Epicurean and Stoic philosophers encountered him. And some said, "What does this babbler want to say?" Others said, "He seems to be a proclaimer of foreign gods," because he preached to them Jesus and the resurrection (vv. 16-18).

What's crucial to notice here, first of all, is Paul's relationship to the culture.

He doesn't try to assimilate. He doesn't embrace the culture and look for ways to shape the gospel to suit it. He is repulsed by it.

Look at verse 16 again: "his spirit was provoked within him when he saw that the city was given over to idols." The Greek word for "provoked" is

paroxuno, which is a very intense word meaning "exasperated" or "agitated." It conveys the idea of outrage and indignation.

Paul, of course, was well educated, and he was fully aware of the history and the details of Greek mythology and the religion of Athens. (He even had memorized passages from Greek poets and writers, as we are about to see.) But this was his first time to be in Athens and see all the temples and the omnipresent idolatry with his own eyes. Wherever he looked, he saw the signs of it—sophisticated, intellectual, completely unspiritual religion that was utterly without any reference to the true God. That was the defining mark of that culture, and it grieved Paul deeply.

So he immediately began confronting the idolatry by proclaiming Christ. Notice: when Luke says in verse 17 that "he reasoned" with people in these public places, he's not suggesting that Paul had cream tea and quiet conversation with them. It means he stood somewhere where people couldn't possibly miss him and began to preach and proclaim like a herald, and then he interacted with hecklers and critics and honest inquirers alike. Luke uses the Greek word

dialegomai, from which our word

dialogue is derived, but the Greek expression is a strong one, conveying the idea of a debate or a verbal disputation. It can also speak of a sermon or a philosophical and polemical argument. Paul did all of that, because he took on all comers.

In fact, in the King James Version, it says he

"disputed . . . in the synagogue with the Jews, and with the devout persons, and in the market daily with [whoever] met with him." That's not to say that he was belligerent or pugnacious, but he

proclaimed the truth about Christ without low-keying the tough parts or shaving all the hard edges off the counter-cultural truths. And then he responded to whatever questions or arguments or objections people raised.

In other words, he

confronted their false beliefs; he did not try to accommodate them. Paul was deliberately and intentionally counter-cultural. He didn't say,

Oh, these people think the idea of bodily resurrection is foolish; I'd better soft-sell that part of the message. He did exactly the opposite. He studied the culture with an eye to confronting people with the very truths they were most prone to reject.

The Philosophers

He wasn't winning any admiration from the intellectual elite for his cultural sensitivity, either. Notice verse 18: "Certain Epicurean and Stoic philosophers encountered him." They were not impressed. They called him a seed-picker and more or less made sport of him.

Who were these guys?

The Stoics were secular determinists who believed the height of human enlightenment was achieved by complete indifference to pleasure or pain. They believed everything is predestined unchangeably by random chance, and therefore nothing really matters in the ultimate sense. They were fatalistic. Think of them as secular hyper-Calvinists with a dose of Greek Mythology defining the theistic elements of their religion. Their goal was self-mastery through the overcoming of the emotions—and they lived austere, simple lives enjoying as few pleasures as possible. The Stoic sect was founded by Zeno around 300 BC, so the system was three and a half centuries old and a mainstay of Greek philosophy when Paul encountered these guys.

The Epicureans were at the opposite end of the philosophical spectrum. They believed the chief end of man was to enjoy pleasure and avoid pain. They indulged in all the finest things and richest pleasures this life had to offer. Epicureanism was likewise 350 years old, and one of its central ideas was that God is not to be feared. They did not believe in life after death, so their one goal was earthly happiness—practically the opposite of Stoicism.

The Stoics and the Epicureans were poles apart on the philosophical spectrum and obviously adversarial in many of their beliefs. There's no doubt that some of the most interesting debates between competing Greek philosophies pitted Stoics against Epicureans and vice versa. But they also shared some of their most fundamental beliefs in common, and those common beliefs were the defining elements of Greek thought and culture. Both philosophies were materialistic and man-centered and therefore they were united in their resistance to all biblical truth.

There was a third major strain of Greek philosophy not named here by Luke—

the Cynics. Even though Cynicism isn't specifically named by Luke, it's almost certain that some Cynics were in the audience. The Cynics believed virtue is defined by nature—and true happiness is achieved by freeing oneself from unnatural vales like wealth, fame, and power and living in harmony with nature. They were first-century hippies, known for their neglect of things like personal hygiene, accountability, family responsibilities, and whatever. Cynicism was the oldest of the three major strains of Athenian philosophy, dating back to about 400 years before Christ, so Cynicism was also an ancient system—450 years old by the time Paul stood in the Areopagus. It was still a robust influence in the culture of Athens, and the Cynics had a peculiar knack for irritating the other philosophers.

Remember, Paul was grieved by Athenian culture. It would be foolish to suggest that he embraced any of the defining spiritual elements of such a culture. His message was counter-culture and disturbing to the ears of Stoics, Epicureans, and Cynics alike.

But some of these high-powered philosophers heard him disputing in the marketplace and thought,

Hey, this guy would be interesting in a discussion with the elite minds of Athens. They could surely tell Paul was an educated man, not just a random crackpot. And yet his ideas seemed so bizarre to their way of thinking that they could not find a way to categorize him neatly in their systems. He was clearly neither Stoic nor Epicurean nor Cynic. He stood in opposition to all of them, and that was obvious, because of what he preached: "Jesus and the resurrection."

And their attitude toward him is obvious: "Some said, 'What does this babbler want to say?'" They used a word that meant "seed-picker"—comparing him to a chicken picking up a seed here and there—as if to say, "He has a cogent thought now and then, but it's so mixed with these strange notions about resurrection that we wonder where he picked up the knowledge he does have. He's rather like a seed-picking bird, pecking and swallowing here and there, but not really very sophisticated."

Paul was clearly out of step with every major system of human wisdom known at the time.

Counter-cultural. That's exactly what they meant by "a proclaimer of foreign gods"—a prophet of some new and unconventional religion that fit nowhere comfortably into the existing culture.

Paul was nevertheless articulate enough and bold enough to catch these philosophers' attention, and that made him something of a

novelty. That, according to verse 21, was something they loved: "For all the Athenians and the foreigners who were there spent their time in nothing else but either to tell or to hear some new thing." Very much like our own culture. Athens was the place to surf the ancient Web and see what's new. Paul was the equivalent of a bizarre but intriguing viral YouTube video.

Mars Hill

So "they took him and brought him to the Areopagus, saying, 'May we know what this new doctrine is of which you speak? For you are bringing some strange things to our ears. Therefore we want to know what these things mean'" (v. 19).

Now that finally gets us into the actual passage we want to survey: Paul's sermon. He is brought to the Areopagus ("Mars Hill" in the King James Version)—named for the place where these philosophers had started meeting centuries before. Here was Paul, surrounded by the most high-powered minds of the most intellectual city in the world, and he has an opportunity to speak to them.

Then Paul stood in the midst of the Areopagus and said, "Men of Athens, I perceive that in all things you are very religious; for as I was passing through and considering the objects of your worship, I even found an altar with this inscription: TO THE UNKNOWN GOD. Therefore, the One whom you worship without knowing, Him I proclaim to you (vv. 22-23).

That is where many people today would say Paul adapted to and embraced their culture rather than being confrontive or antagonistic to the culture, because he begins with a reference to their beliefs (and especially the religious culture) of the city, and he makes

that the point of contact.

But now remember, we have to read this in light of its own context, and verse 16 says this was the very aspect of Athenian culture that most grieved Paul. In other words, he homed in on the one point of culture that most disturbed him and began there, because that is what he most wanted to challenge. The false gods of Athens embodied the main lie he wanted to answer with the truth, and he made a beeline for it: "You are very religious," he says. "I can see it everywhere."

But the truth is, they

weren't religious at all. They had all the trappings of religion, with temples and idols everywhere. But their ancient religions were nothing but superstition run amok, but all of that had long ago morphed into a simple love of human wisdom. That's what they worshiped: "The Greeks seek after wisdom" (1 Corinthians 1:22). Philosophy was the only god they really served.

The Epicureans didn't even believe in an afterlife, and the Stoics were materialists whose God was an amorphous and utterly impersonal notion of blind (but sovereign) chance. The Cynics deified nature. In other words, all the major strains of Greek philosophy were fundamentally materialistic. They had fashioned a kind of quasi-spirituality that in fact was not

spiritual at all. None of them believed in a personal God. None of them had any higher value than human wisdom. Their ethics were naturalistic and materialistic. They were practical atheists—in many ways a mirror of our own society today.

They weren't truly religious at all. Paul was using sanctified sarcasm when he started out by observing how religious they were.

Now, their culture, like ours, had all the

trappings of religion, and they were omnipresent: temples on every corner, idols, priests and priestesses, and lots of superstitions and deeply-ingrained traditions. But these were almost entirely devoid of any kind of true faith. That stuff just saturated all society. It had the very same significance as all the cathedrals in Europe today, or all the church buildings you'll see if you drive through New England.

The Unknown God

But in the tradition of their polytheistic mythology, the Greeks deified everything. There was a god of war (Ares); the sun god (Apollo); Hades, the Lord of the underworld; Hermes, the messenger-god; Poseidon, God of the sea; and Zeus, king of the gods. And those were just the

Olympian gods. There were also

primordial gods, including Aether, the god of the atmosphere; Chronos, the god of time; Eros, the god of love; Erebus, the god of shadow, and many more. Then there were the

Titans, and the

nymphs, and the

giants, the river god, and hundreds of lesser gods. And of course no educated person in Athens really believed any of those gods were real, but they were part of the culture's mythology.

And when they ran out of things to deify, someone decided to erect a monument to whatever god there might be who was overlooked by the Greek system, just so that no deity was inadvertently slighted. They had this altar "To the Unknown God." Sort of like the tomb of the unknown soldier, but motivated by sheer superstition. Just in case they overlooked giving honor to a hidden deity somewhere, they had an altar that covered the bases.

Paul had seen that altar, and he seized on it for the opening of his message.

This was by no means an affirmation of their culture. Just the opposite. It was Paul's way of homing in on what was spiritually most odious about the culture. In this quasi-religious, deeply superstitious, man-centered intellectual culture—here was an altar to something

unknown. The irony was rich, because what they really worshiped was human wisdom and knowledge, but here was an altar to something they were admittedly ignorant about. And Paul more or less rubs salt in that wound. He places the accent on their utter

ignorance of the one thing that matters most:

This God whom you are utterly ignorant about; that's the God whose name I want to declare to you.

Don't miss what Paul was doing here.

He wasn't shoe-horning God into an open niche in Greek mythology. He wasn't affirming their beliefs or embracing this aspect of their culture at all. He was seizing on this one supremely important point where they admitted their own ignorance, and he was using that as a foot in the door so that he could proclaim to them the gospel. As far as the religious aspect of their culture was concerned, he stood against it, and this opening statement made that fact absolutely clear to them. Far from using "culture" as a kind of pragmatic or ecumenical bridge in order to get himself into their inner circle and become a part of their group in order to win them, he stands in their midst as an alien to their culture and (in his own words)

proclaimed the truth about God to them.

It was as if someone got in the midst of a bunch of academic postmodernists today and declared that the Bible is true. Just imagine an auditorium full of 21st-century university professors wringing their hands about epistemological humility and the dangers of overconfidence and the uncertainty of human knowledge and the subjectivity of all our opinions—and the whole dose of postmodern angst about being sure about anything. And suppose you stood up in front of that group with a Bible and declared, "Here's something you can be rock-solid certain about, because God Himself revealed it as absolute truth."

That's what this was like. It's hard to imagine any way he could have been more counter-cultural.

PS:

PS: Hang on. There's lots more to come.

harity is defined in 1 Corinthians 13. Among other things, it "does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth" (v. 6).

harity is defined in 1 Corinthians 13. Among other things, it "does not delight in evil but rejoices with the truth" (v. 6). It sounds pretty silly even to raise that question, doesn't it? You know he didn't. He simply proclaimed the message Christ had given him to preach—"not with persuasive words of human wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power" (1 Corinthians 2:4). Just as Paul had always done, he headed straight for the one truth he knew very well would sound most like utter foolishness to them: the resurrection of the dead.

It sounds pretty silly even to raise that question, doesn't it? You know he didn't. He simply proclaimed the message Christ had given him to preach—"not with persuasive words of human wisdom, but in demonstration of the Spirit and of power" (1 Corinthians 2:4). Just as Paul had always done, he headed straight for the one truth he knew very well would sound most like utter foolishness to them: the resurrection of the dead.

QUESTION: Where are the hordes of postmodernists, Emergent/emerging aficionados, and evangelical contextualizers who said they wanted to have a conversation about Acts 17? Not so long ago, people were crawling out of the woodwork to assert the necessity of seeking "common ground" with hostile worldviews. They insisted we must adapt our message to fit (rather than confront) unbelieving cultures. They were touting a brand of "missional" strategy where building bridges to other worldviews is supposed to be more important than demolishing them (contra 2 Cor. 10:4-5). So I've been making

QUESTION: Where are the hordes of postmodernists, Emergent/emerging aficionados, and evangelical contextualizers who said they wanted to have a conversation about Acts 17? Not so long ago, people were crawling out of the woodwork to assert the necessity of seeking "common ground" with hostile worldviews. They insisted we must adapt our message to fit (rather than confront) unbelieving cultures. They were touting a brand of "missional" strategy where building bridges to other worldviews is supposed to be more important than demolishing them (contra 2 Cor. 10:4-5). So I've been making

gain: there is an obvious and legitimate need to speak a language people understand if you want to reach them. Paul didn't go into Athens and speak Hebrew to the Areopagites. He spoke Greek. There's nothing the least bit remarkable about that. What Paul did not do was adapt his message to suit the basic values and belief systems of that culture.

gain: there is an obvious and legitimate need to speak a language people understand if you want to reach them. Paul didn't go into Athens and speak Hebrew to the Areopagites. He spoke Greek. There's nothing the least bit remarkable about that. What Paul did not do was adapt his message to suit the basic values and belief systems of that culture. For one thing, in verse 24-25, when he says, "The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything"—Paul was summarily dismissing all the fundamentals of Greek-style religion. Paul certainly knew what Greek mythology taught. And the Athenian Philosophers weren't naive about world religions either. It wasn't as if they were clueless about Judaism or the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Paul wasn't introducing them to a God they had never heard of. He was telling them as plainly as possible that their beliefs were wrong.

For one thing, in verse 24-25, when he says, "The God who made the world and everything in it, being Lord of heaven and earth, does not live in temples made by man, nor is he served by human hands, as though he needed anything, since he himself gives to all mankind life and breath and everything"—Paul was summarily dismissing all the fundamentals of Greek-style religion. Paul certainly knew what Greek mythology taught. And the Athenian Philosophers weren't naive about world religions either. It wasn't as if they were clueless about Judaism or the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Paul wasn't introducing them to a God they had never heard of. He was telling them as plainly as possible that their beliefs were wrong. aul declared the truth in the Areopagus without apology, without undue respect for their academic stature, and without artificial deference to their points of view. He preached the gospel; he did not sponsor a colloquium about it. In the synagogue and marketplace of Athens, Paul had engaged in discussions and debates about the gospel (Acts 17:17), but these were no doubt the typical sort of give-and-take every open-air evangelist would have with hecklers, inquisitive people, people under conviction, and people who are simply curious. Paul would have answered any

aul declared the truth in the Areopagus without apology, without undue respect for their academic stature, and without artificial deference to their points of view. He preached the gospel; he did not sponsor a colloquium about it. In the synagogue and marketplace of Athens, Paul had engaged in discussions and debates about the gospel (Acts 17:17), but these were no doubt the typical sort of give-and-take every open-air evangelist would have with hecklers, inquisitive people, people under conviction, and people who are simply curious. Paul would have answered any  questions or objections that came to him. It is inconceivable that he might have been holding round-table discussions with the goal of finding "common ground" and winning Athenians with persuasive words of human wisdom.

questions or objections that came to him. It is inconceivable that he might have been holding round-table discussions with the goal of finding "common ground" and winning Athenians with persuasive words of human wisdom.

ead (and believe) enough of the trendy books and blogs that talk about missional living, and you'll get the distinct impression that fitting into this world's cultures is vastly more important—and a much more effective evangelistic strategy—than knowing the gospel message and communicating it with boldness, precision, and clarity.

ead (and believe) enough of the trendy books and blogs that talk about missional living, and you'll get the distinct impression that fitting into this world's cultures is vastly more important—and a much more effective evangelistic strategy—than knowing the gospel message and communicating it with boldness, precision, and clarity. Paul, of course, was well educated, and he was fully aware of the history and the details of Greek mythology and the religion of Athens. (He even had memorized passages from Greek poets and writers, as we are about to see.) But this was his first time to be in Athens and see all the temples and the omnipresent idolatry with his own eyes. Wherever he looked, he saw the signs of it—sophisticated, intellectual, completely unspiritual religion that was utterly without any reference to the true God. That was the defining mark of that culture, and it grieved Paul deeply.

Paul, of course, was well educated, and he was fully aware of the history and the details of Greek mythology and the religion of Athens. (He even had memorized passages from Greek poets and writers, as we are about to see.) But this was his first time to be in Athens and see all the temples and the omnipresent idolatry with his own eyes. Wherever he looked, he saw the signs of it—sophisticated, intellectual, completely unspiritual religion that was utterly without any reference to the true God. That was the defining mark of that culture, and it grieved Paul deeply. There was a third major strain of Greek philosophy not named here by Luke—the Cynics. Even though Cynicism isn't specifically named by Luke, it's almost certain that some Cynics were in the audience. The Cynics believed virtue is defined by nature—and true happiness is achieved by freeing oneself from unnatural vales like wealth, fame, and power and living in harmony with nature. They were first-century hippies, known for their neglect of things like personal hygiene, accountability, family responsibilities, and whatever. Cynicism was the oldest of the three major strains of Athenian philosophy, dating back to about 400 years before Christ, so Cynicism was also an ancient system—450 years old by the time Paul stood in the Areopagus. It was still a robust influence in the culture of Athens, and the Cynics had a peculiar knack for irritating the other philosophers.

There was a third major strain of Greek philosophy not named here by Luke—the Cynics. Even though Cynicism isn't specifically named by Luke, it's almost certain that some Cynics were in the audience. The Cynics believed virtue is defined by nature—and true happiness is achieved by freeing oneself from unnatural vales like wealth, fame, and power and living in harmony with nature. They were first-century hippies, known for their neglect of things like personal hygiene, accountability, family responsibilities, and whatever. Cynicism was the oldest of the three major strains of Athenian philosophy, dating back to about 400 years before Christ, so Cynicism was also an ancient system—450 years old by the time Paul stood in the Areopagus. It was still a robust influence in the culture of Athens, and the Cynics had a peculiar knack for irritating the other philosophers. Don't miss what Paul was doing here. He wasn't shoe-horning God into an open niche in Greek mythology. He wasn't affirming their beliefs or embracing this aspect of their culture at all. He was seizing on this one supremely important point where they admitted their own ignorance, and he was using that as a foot in the door so that he could proclaim to them the gospel. As far as the religious aspect of their culture was concerned, he stood against it, and this opening statement made that fact absolutely clear to them. Far from using "culture" as a kind of pragmatic or ecumenical bridge in order to get himself into their inner circle and become a part of their group in order to win them, he stands in their midst as an alien to their culture and (in his own words) proclaimed the truth about God to them.

Don't miss what Paul was doing here. He wasn't shoe-horning God into an open niche in Greek mythology. He wasn't affirming their beliefs or embracing this aspect of their culture at all. He was seizing on this one supremely important point where they admitted their own ignorance, and he was using that as a foot in the door so that he could proclaim to them the gospel. As far as the religious aspect of their culture was concerned, he stood against it, and this opening statement made that fact absolutely clear to them. Far from using "culture" as a kind of pragmatic or ecumenical bridge in order to get himself into their inner circle and become a part of their group in order to win them, he stands in their midst as an alien to their culture and (in his own words) proclaimed the truth about God to them.

n Acts 17, Paul preaches to the intellectual elite of Athens. The narrative includes one of the classic examples of New Testament gospel-preaching. It shows us the apostolic evangelistic strategy in action. It's an especially helpful example of how to confront false religion, philosophy, and elitism in an evangelistic setting. And it takes place in a highbrow academic environment. It's one of the best-known portions of the book of Acts, but it's also one of the most-abused sections in all of Scripture. It's a favorite passage for those who insist if we're not finding (or creating) as much common ground as possible between church and culture we are not properly contextualizing the gospel.

n Acts 17, Paul preaches to the intellectual elite of Athens. The narrative includes one of the classic examples of New Testament gospel-preaching. It shows us the apostolic evangelistic strategy in action. It's an especially helpful example of how to confront false religion, philosophy, and elitism in an evangelistic setting. And it takes place in a highbrow academic environment. It's one of the best-known portions of the book of Acts, but it's also one of the most-abused sections in all of Scripture. It's a favorite passage for those who insist if we're not finding (or creating) as much common ground as possible between church and culture we are not properly contextualizing the gospel.

efore the 1970s, the word contextualize was pretty hard to come by. It was, however, listed in unabridged dictionaries as a verb meaning "to study something in its own context." (The Oxford English Dictionary still gives that as the word's primary meaning.)

efore the 1970s, the word contextualize was pretty hard to come by. It was, however, listed in unabridged dictionaries as a verb meaning "to study something in its own context." (The Oxford English Dictionary still gives that as the word's primary meaning.)

Here's a handy index to this entire series:

Here's a handy index to this entire series:

remarked in a message at the Shepherds' Conference two weeks ago that I'm not a fan of the word contextualization—or the set of ideas usually associated with that word. Although the message was generally well-received by the pastors who heard it in person, it unleashed an avalanche of forceful reactions from people in the blogosphere—ranging from shocked disbelief to angry derision. The former reaction came from people who gave me the benefit of the doubt. They were merely stunned at my astonishing naïveté. The latter brickbats came from less sympathetic folk, a couple of whom said that they have pretty much always thought of me as a fundamentalist cretin anyway.

remarked in a message at the Shepherds' Conference two weeks ago that I'm not a fan of the word contextualization—or the set of ideas usually associated with that word. Although the message was generally well-received by the pastors who heard it in person, it unleashed an avalanche of forceful reactions from people in the blogosphere—ranging from shocked disbelief to angry derision. The former reaction came from people who gave me the benefit of the doubt. They were merely stunned at my astonishing naïveté. The latter brickbats came from less sympathetic folk, a couple of whom said that they have pretty much always thought of me as a fundamentalist cretin anyway.