In crafting my maiden-voyage post for this series, I had a number of things in mind. Some ended up reading my mind (poor souls) pretty well, while other nascent thoughts were left on the dusty shelves. To save you a click, here it was:

To profess certainty, non-Christians must feign omniscience.The first thought touches on what I might call the "Far Side of Neptune" argument.

Christians begin with the confession that they (1) do not possess omniscience, but (2) are by grace confidants of the only one who does possess it.

Thus Christians alone not only can be, but are obliged to be, humbly certain.

Just think of all the "scientific" theories in all of human history that have died horrible deaths in the light of new discoveries. The positions were always held with great confidence right up to the moment they had to be abandoned...and sometimes even afterwards. One new fact, or one new set of facts, provoked a paradigm-shift, however eventual and reluctant.

So, how many facts are there, in the universe, total? More than ten? More than a trillion? More than ten decazillion, cubed? Of course, we could never even guess the number — let alone their nature — of all facts.

That being the case, who can say with certitude that one fact, existing only ten miles under the surface of the far side of Neptune, and only within an eight-inch radius, would not change everything we think we know about... any given subject? One can scoff, he can dismiss, he can bluff... but he can't answer that question. He cannot honestly say that he knows for a certainty, one way or the other, that some fact not yet in evidence would not constitute a transformative, revolutionary revelation.

Yet nobody lives with such uncertainties. Nobody speaks exclusively in the subjective mood. We love the indicative, even more than we should.

So we announce that (say) evolution is an undeniable fact, that the world is X-zillion years old, that homosexuality is not a chosen behavior, that the unborn are not human, that this or that is right or wrong. We speak as if from a perspective of not only omniscience, but omnisapience; as if we both possessed and understood all facts... even though neither is true.

Yet someone has to keep pointing out the emperor's illusory garb: unless the speaker has an infinite grasp of both the identity and the meaning/significance of every last fact in the universe, he has no right to speak with certainty.

Yet the unbeliever regularly does so speak. He does not possess omniscience. He merely feigns it. His intent is to cow opposition (and quiet his own conscience [Rom. 1:18ff.]) by a show of bravado. As we have seen, the tactic often works in the short run.

A second idea lurked under the surface: "Thus Christians alone not only can be, but are obliged to be, humbly certain." The Christian, insofar as he actually practices the faith he professes, necessarily affirms the inerrancy of Scripture as the very word of God. In so doing, he claims to possess a revelation from the only one who actually does know and understand absolutely everything that exists, since He is the Creator of absolutely everything that exists.

Ironically, however, there are those who (A) claim to be Christian, but (B) choose to feign uncertainty on unpopular issues where the Bible is pretty clear.

These are not murky penumbras, but clear doctrines. Not that a devoted opponent cannot fabricate some murk; it is axiomatic that great distance from the Word necessarily creates greater murkiness (Isa. 8:20). Any clear statement can be smudged... including this one. But the professed believer who adopts a pose of tentativeness on such issues is in the precise-reverse position of the unbeliever who adopts the pose of certitude.

Because (to allude to another terse post that could have been developed further), if God actually has spoken, everything changes.

In sum: the person who denies God's revelation is obliged to speak uncertainly about everything; the person who affirms God's revelation is obliged to speak certainly about some things (Amos 3:8; Acts 4:19-20; 5:29; 1 Cor. 9:16).

The strange thing is that one so often sees the exact reverse.

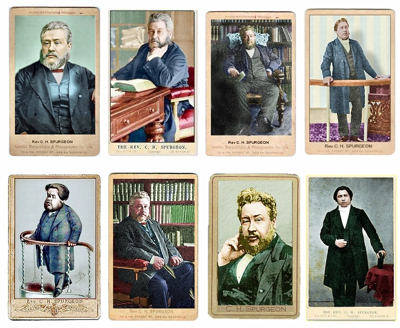

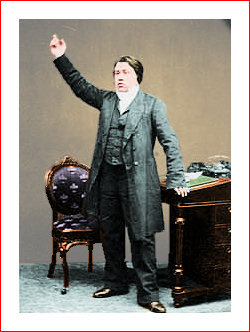

f all the philosophers in the world should contradict the Scriptures, so much the worse for the philosophers; their contradiction makes no difference to our faith. Half a grain of God’s word weighs more with us than a thousand tons of words or thoughts of all the modern theologians, philosophers, and scientists that exist on the face of the earth; for God knows more about his own works than they do. They do but think, but the Lord knows.

f all the philosophers in the world should contradict the Scriptures, so much the worse for the philosophers; their contradiction makes no difference to our faith. Half a grain of God’s word weighs more with us than a thousand tons of words or thoughts of all the modern theologians, philosophers, and scientists that exist on the face of the earth; for God knows more about his own works than they do. They do but think, but the Lord knows.

lain truth is in this wonderful century of small account; men crave to be mystified by their own cogitations. Many glory in being too intellectual to receive anything as absolute certainty: they are not at all inclined to submit to the authority of a positive revelation. God's word is not accepted by them as final, but they judge it and believe what they like of it.

lain truth is in this wonderful century of small account; men crave to be mystified by their own cogitations. Many glory in being too intellectual to receive anything as absolute certainty: they are not at all inclined to submit to the authority of a positive revelation. God's word is not accepted by them as final, but they judge it and believe what they like of it.

e have gospels nowadays which I would not die for, nor recommend anyone of you to live for, inasmuch as they are gospels that will be snuffed out within a few years. It is never worthwhile to die for a doctrine which will itself die out.

e have gospels nowadays which I would not die for, nor recommend anyone of you to live for, inasmuch as they are gospels that will be snuffed out within a few years. It is never worthwhile to die for a doctrine which will itself die out.

It's completely phony for scientists to purloin the gravitas of their work from the creator and sustainer God by assuming without cause that all things are created and thereafter sustained -- but it's equally phony for those of us who say we believe in the creator and sustainer to believe that somehow what He has already said is subject to the same skepticism we should hold toward the discoveries of those who, on a regular basis, are baffled by what they uncover.

It's completely phony for scientists to purloin the gravitas of their work from the creator and sustainer God by assuming without cause that all things are created and thereafter sustained -- but it's equally phony for those of us who say we believe in the creator and sustainer to believe that somehow what He has already said is subject to the same skepticism we should hold toward the discoveries of those who, on a regular basis, are baffled by what they uncover.

ome persons appear to think that a state of doubt is the very best which we can possibly reach. They are very wise and highly cultured individuals, and they imagine that by their advanced judgments nothing in the world can be regarded as assuredly true.

ome persons appear to think that a state of doubt is the very best which we can possibly reach. They are very wise and highly cultured individuals, and they imagine that by their advanced judgments nothing in the world can be regarded as assuredly true.

he church of Christ . . . desires not to be associated with other armies, or to be mistaken for them, for it is not of this world, and its weapons and its warfare are far other than those of the nations.

he church of Christ . . . desires not to be associated with other armies, or to be mistaken for them, for it is not of this world, and its weapons and its warfare are far other than those of the nations.

his blog is not a place where we just think out loud. The stuff we write about tends to focus on a few (mostly important) issues we have thought a lot about and studied with some degree of care—mostly things we're pretty passionate about. Our opinions on such matters do tend to be fixed enough that it would take a lot more to change our minds than the musings of some fresh-faced high-school graduate who is just reacting in the comments section of our blog to an issue he has never before devoted 20 seconds thought to untangling.

his blog is not a place where we just think out loud. The stuff we write about tends to focus on a few (mostly important) issues we have thought a lot about and studied with some degree of care—mostly things we're pretty passionate about. Our opinions on such matters do tend to be fixed enough that it would take a lot more to change our minds than the musings of some fresh-faced high-school graduate who is just reacting in the comments section of our blog to an issue he has never before devoted 20 seconds thought to untangling. Who is more "arrogant"? Someone who refuses to compromise even when popular thinking shifts against him, or the guy who never really settles on any truth and yet constantly argues about everything anyway—not because he himself has stumbled on something he is certain about, but merely because his contempt for other people's strong convictions is the way he justifies his waffling in his own mind?

Who is more "arrogant"? Someone who refuses to compromise even when popular thinking shifts against him, or the guy who never really settles on any truth and yet constantly argues about everything anyway—not because he himself has stumbled on something he is certain about, but merely because his contempt for other people's strong convictions is the way he justifies his waffling in his own mind?

he brilliance of the gospel light is dimmed by error. The clearness of the testimony is spoiled when doubtful voices are scattered among the people, and those who ought to preach the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, are telling out for doctrines the imaginations of men, and the inventions of the age.

he brilliance of the gospel light is dimmed by error. The clearness of the testimony is spoiled when doubtful voices are scattered among the people, and those who ought to preach the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth, are telling out for doctrines the imaginations of men, and the inventions of the age.

f our postmodern friends are correct and all certainty is arrogance, wouldn't personal assurance of one's own salvation be just about the ultimate conceit?

f our postmodern friends are correct and all certainty is arrogance, wouldn't personal assurance of one's own salvation be just about the ultimate conceit?