by Frank Turk

Warning to all readers: this is 9 pages single-spaced in WORD, so pack a lunch.

Dear Greg and Cameron,

First, thanks for

your reply to my open letter to Chris Stedman. A reply is always nice rather than, as has been the case in several other open letters, being talked about, or merely scorned via Twitter, and I credit you for it. I see it as an open door to actually making some headway on some of the issues my letter laid out, and then some of the issues your letter laid out either in opposition or as a basis for finding out what the much-vaunted "way forward" is.

Before we get to the text of your letter, there’s also a down-side to what you posted: the substance of the comments which followed. This is the internet, after all, and what’s most obvious about the internet is that

someone on it is wrong. That fact drives so much of the bandwidth for most blog posts which real-live human beings read that when one finds a blog post which has no detractors commenting, one has to wonder if anyone has read that blog at all.

And this is Chris’ blog we’re talking about, so I hope that a guy like this who get face time at the Huffington Post will have a few people pass by to check in on him and his exploits. He’s no humanist Challies, to be sure, but my thought is that someone would wander past his blog in the course of three weeks and read your post and find something to critique, if not something to disagree with outright. But there is a curious absence of any detractors.

There are probably 500 hypothetical permutations of why this might be true, but let me say frankly that I know for a fact why it is true: posts with criticisms don’t get past the Blogger approval screen. I know that for a fact because I posted several comments there – all only pointing out that I disagree with you – and they never appeared. I thought it was my iPod for the first post, so I tried from both my PowerBook and my work laptop, and none of those comments appeared, either.

So as we consider

the nature of the kind of "conversation" Chris is promoting, at least place in the field of consideration that actual dissention from his version of "better together" orthodoxy doesn’t make the cut when he is allowed to choose the method of engagement. You can compare that to what happens routinely here where people are allowed to say almost anything for dozens of comments before they are asked to reign it in. Ask yourself which is a "discussion" and which is something else.

Important correction: Chris did chime in in the comments below to say that he did not see my comments at all in his administrative filter -- that in fact those comments simply got lost in the bandwidth. Having been the victim of the Internet at my own various blogs myself, I take him at his word, and I stand corrected on the cause of the lack of detractors on his own blog posts. Let this correct the record.

Now: that's just the preface. I wanted to go through your reply and see if there’s anything I can learn from you, and that with some luck or God’s grace you might learn from me. We’ll see how that all pans out between us.

You begin:

While we as Evangelical Christians discuss frequently on our site the importance of interfaith relationships – including relationships with those of a secular tradition – we are reminded that not everyone sees things the way we do.

Earlier this week, our friend Chris Stedman, a secular humanist and a leading voice for the involvement of the nonreligious in interfaith cooperation, was the target of an open letter written by Frank Turk, contributor to a Christian blog "PyroManiacs" (tagline: "Setting the world on fire…"). We wanted to respond – not because a response was invited, but because we are Evangelical Christians, we disagree with the approach to religious difference that particular Christians ("PyroManiacs" included) have taken, and because we are offended by the idea that someone representing Jesus Christ would make some of the statements that were made toward Chris.

This is an interesting approach to your reply, because I think it goes back to the problem of what constitutes a "discussion". See: Chris is your "friend" who is a "leading voice" and I am a blogger who "targets" him – in spite of the fact that (let’s face it) I am actually a "leading voice" in the blogosphere as are my fellow blog-mates here at PyroManiacs. This blog ranks in the top 10 of all "Lifestyle" blogs consistently, and in the top 5 "Religion" blogs as well. I wonder if you intended that immediate distinction between what Chris does and what I do – or if it was unintentional and a function of your already-formed conclusions? You’re certainly welcome to the latter – I think well-formed conclusions are the basis for real dialog and real improvement of all manner of things. But factually, you have started your piece by marginalizing me and telling the reader that Chris is the credible one, and your friend.

In terms of starting a "discussion", I wonder if I started a discussion this way about Chris you would find it in any way fair – let alone constructive.

You continue:

Turk’s "Open letter" centers on a tweet posted earlier this month that read: "Exciting to hear about how @ChrisDStedman is reshaping the conversation between religious and nonreligious." While Turk seemingly attempts to belittle Chris’s work by calling out his sexuality and tattoos, we are reminded of the very need for reshaping just such a conversation. Turk asks "Is that really ‘reshaping’ anything?"—in other words, is Chris really making a difference? And later implies that dialogue won’t change humanity’s propensity to, as he calls it, "err," calling into question the very efficacy of the interfaith endeavor. We contend that Chris Stedman is in fact reshaping the conversation, and that constructive dialogue is playing a great part in this.

One thing I would point out to you here is that your summary of my "open letter" (scare quotes and all) is entirely reductive and frankly unreflective of what I actually said. That’s a far cry from what I did for Chris in my open letter by introducing him to my readers with his own words, and his own description of himself. In fact I said this to him:

I mean: what I took away from the HuffPo piece was that you think there's a common cultural context that people with and without religion can sort of participate in, and that they can cooperate with each other to achieve some kind of socio-political good together. Is that really "reshaping" anything?

I think it can reshape the atheist evangel, to be sure -- it will move the popular atheist stereotype out of the ghetto of cage-stage positivism and adolescent nihilism/hedonism into a plump, congenial middle-age. This kind of thinking is frankly understood as the norm in Europe, and to say and do otherwise there is shocking. But American atheism has been a lot like American fundamentalism at least from the days of the vile Madalyn Murray O'Hair, and its ability to seek converts through fear and intimidation has probably been a very powerful factor in keeping it a marginal ideology. So kudos to you for being a stand-up guy for humanism rather than something and someone less concerned about a so-called path forward in a multicultural world.

That’s pretty significantly more-generous than your Reader’s Digest version.

The next paragraph sounds very nice (we’ll get there in a second), but so far I think that you don’t really mean what you say there – for one reason only: it’s not what you practice. And given that Chris endorses your way of doing this – both by publishing your response, and by prefacing it with his very-glowing approval – I doubt he really wants a "discussion" either. What he wants is people to agree with him, and to talk with people who agree with him. That’s not much of a conversation: it’s more of a mutual admiration society. What kind of dialog are you looking for when this is how you treat people who disagree with you?

Here’s what you say next, before I go on:

The conversation "between religious and nonreligious" as mentioned in the tweet is not a two-way discussion between Christians and atheists; rather, Christians and atheists are simply two pieces of a much broader discourse among peoples of all different faith traditions, worldviews, philosophies, and perspectives. Whether it is a church being bombed in Egypt, a pastor threatening to burn the Qur’an, or the recent protests of a Muslim community fundraiser in California, we would say that conversations around religious differences still need some major remodeling. And in the arena of atheists’ relationship to religion in particular, Chris is doing phenomenal work to show that being a non-religious person does not mean one has to be aggressively anti-religious. As a religious man himself, Turk should at least grant this much in Stedman’s favor.

Now, this is exactly what I mean. As you can see

from quoting my open letter, I did say

exactly that about what Chris has done. Turk did in fact "grant this much in Stedman’s favor." It’s hard to deny when you look at it, in fact – but you have explicitly denied it, haven’t you?

Why? Maybe – and I think this is likely – you skimmed my open letter, or didn’t read it at all. What you found was an old guy who said something you believed would be disagreeable about your friend, and you felt like you needed to say something in response which makes it clear that Chris is your friend and I am not. Fair enough: but does actually saying untrue things – you know: saying I did not give Chris any credit for working the Atheist fundamentalists over when in fact I said explicitly that he’s doing that and it is a good thing – work out to improve me, or make some point about Chris contra my point about Chris?

Probably not – but here’s what I’m willing to do at this point: I’m willing to chalk it up to youthful hubris and collegiate spirit because I was once one such as you – or more realistically, more like Chris as I was an atheist in college. I’m sure that’s news to you, but it’s not any kind of a secret. I like to call it the surprise in the Cracker Jack box which is my faith and mission as a blogger: surprising people with the idea that there are really folks who have walked the field of faithlessness and come out the other end with a different conclusion. But I say that only to say this: if there were actually any discussion going on, you’d probably have discovered that.

Instead, you took it for granted that I was one kind of person, and I think – in fact, I know – I am someone else entirely. That you cannot read my most generous statement about Chris in even a remotely-fair (let alone generous) way, speaks to that directly, and clearly, and to your own discredit. That Chris did not see that or offer you a chance to revise your way out of that prior to endorsing you and signing off on you as a credible replica of Jesus also speaks to his own blinders in this matter.

Now, from that, you jump to this without any bridge:

We believe that interfaith cooperation efforts—and atheists/humanists’ involvement in them— are relevant, timely, and crucial in today’s global society, and that they stand in line with the values espoused by Christ to love one’s neighbor and bring peace to the world. Chris Stedman has contributed greatly to the cause of interfaith cooperation, making it a visible and vibrant part of the discussion happening on university campuses all across the country.

I agree. In fact, my quote proves I agree. It turns out that we agree about this – yet with your lead-up to it, the casual reader of your post will think I do not agree with either you or Chris or Jesus. This is especially troubling when we read your next paragraph:

Because the model for interfaith cooperation to which we adhere depends upon mutual respect, value judgments on the morality of human sexuality or concern with one’s personal choices lie largely beyond the purview of the discussion. We, like Chris, simply advance the message of peace and sociological pluralism. Our concern is not with individual religious practice or belief or widespread social concerns except where they intersect with violence, strife, and bigotry. Our own Christian religious identity informs our desire to build bridges of cooperation with those of other traditions and worldviews, but does not in any way muddy our own values or compel us to entreat them on others.

As we say on this side of sociological pluralism, "Aha!"

Let’s start with the underlined part rather than the last sentence. That statement is so utterly incomprehensible in the context you provided it that I have to work through it with you. Let’s ask a simple question: would someone who tells lies, for example, be welcome in your circle of cooperation? I’m thinking not of someone spreading malicious gossip or actually framing the statements of someone else in such a way to make them a bad guy: I’m thinking of someone who was in your fold of cooperation who did not share all your objectives of "peace and sociological pluralism". Maybe this person actually had the objective of eliminating meaningful distinctions between any two of the cooperating sociologically-plural identities in order to eliminate one or both of them. Would that person’s "concern with one’s personal choices" really not matter to you? If not, how can you say you actually want any kind of pluralism – that you actually respect the differences between those who are different?

As you ponder that, let’s then approach your last sentence there with some gusto. You say your desire to "build bridges" does not in any way "muddle the waters" of your own core values – but that is also completely and transparently false. The fact that you’re careless with the truth toward those who disagree with you ought to indicate to you that this is less than compelling – but the fact that this endeavor is itself dubious in real sociological improvement ought to also put a twinge in your "Evangelical" (scare quotes intended) funny bone.

See: you are using great timeless words to describe your objectives – "peace", and "respect" vs. "violence, strife and bigotry." You might as well be saying you’re in favor of ice cream and against feeding babies BP oil spill tarballs. Who exactly would come out and say, "Bigotry saved my family, and I’m proud to hate people based on stereotypes," or "strife is just a hobby; I’m actually a professional force of malevolence?" Prolly no one, I am sure you will admit. Nobody is actually in favor of bigotry, violence and strife – when you put it that way. The problem, of course, is that adult humans never put it that way.

And therein lies the real problem. Think about the striking civil servants in Wisconsin for a moment. They are causing a lot of strife, no? They have put children out of school, taken police off the street, disrupted the capital of their state, and so on. But if you ask them, what they are doing is

combating the strife caused by the Governor and the elected conservative majority in the state government, right? So it’s actually the Governor and his agenda who caused all this strife. Or maybe it’s the people of WI who elected these characters who caused all the strife – you know: they voted for a guy and his political buddies who promised to balance the budget and end deficit spending in state government.

I mean: we’re against strife – but if that’s true, do we overturn the election results in WI to oppose strife? How do we oppose strife

in actual examples unless we get our difference out in front of us?

This is where what you think you’re standing up for falls apart – and it’s at the core of my letter to Chris, but you missed it there, so I’ll rephrase it here for your sake. In real life, the problem is not what we might agree on: it’s what we do not agree on that causes us to have to choose a new course of action, and simply affirming each other for what we think are our good points does not get us anywhere.

Should airing disagreement have to be a war of attrition? Your open letter says yes (as above, and as we’re going to get to, below – that is, you have to take the other guy down and out in order to dismiss him [not win him]), but factually it does not. What it does have to do, though, is

recognize that there are reasons for our differences, and mull them over in a way which sizes up the real choices we are about to make if we are going to be "better together".

The WI civil employee union strikes are just one example – but others far more wide-spread are easy to think of. Should abortion be legal? If so, is it just a medical procedure? What if our policy causes

more black babies in NYC to be aborted than to be born – does it turn out that abortion law is racist in practice? Is that bad? How do we know?

A better example is Chris’ most recent public preaching against hearings about Muslims to be conducted in Congress – and at the same time coming out to say we need to hear "more Muslim voices". Do you not find any irony at all in the fact that the lack of Muslim voices (except for extremists) has caused some of our elected representatives to call for hearings so that the Muslim community will speak up for itself – and Chris opposes that? How do we discover the right way to "hear more Muslim voices"? Can we do that if our core sociological ethic is to overlook others’ personal values?

In your view, we can just overlook personal moral choices and be joined in some kind of sociological group hug and it all gets better. But in practice – and I mean, to even get off the bench to start stretching before the actual game – there’s no way that makes one iota of difference in effecting change.

Now, seriously – this is my favorite part of your response:

Dialogue, though discounted in Turk’s letter, has the power to produce empathy through understanding. Part of the goal of interfaith cooperation is not simply an end to something (i.e. violence), but is actually a positive, proactive movement built around service that aims to improve our world and address the problems we face. (See Greg’s post on the Million Meals for Haiti even at UIUC for an example of this.)

Again, Aha!

Do I need "epathy and understanding" to think to myself, "huh! The people in Haiti who have been decimated for more than a year by the aftermath of a natural disaster probably need something to eat!" Or do I just need the raw facts? I mean: even the Southern Baptist Convention can mobilize for the Red Cross (and does so) without checking anyone’s baptism certificates. Is that really a wild leap forward for "interfaith dialog", or does it turn out that you guys just found out that this happens in real life all the time, and that it happens mostly when people can agree on really gigantic incidents of suffering? The problem is not seeing the gigantic incidents of suffering: everyone can see those, and no one with a Western values system will tell you that humanitarian aid is uncalled for. The problem is that you guys think that this is new, and an innovation, and a neoteric way to do society – and that it’s the most important thing you can be concerned about.

Here’s how I know that:

As devout Christians, we understand the desire and imperative to point to Christ as the answer to any perceived iniquity; we want our friends to know Christ and his saving grace. Yet we often struggle with the way the church presents these messages of salvation to the world, having been frustrated by our own past experiences.

Chris Stedman, once a church-going Christian himself, doesn’t need a lesson on the teachings of Christ or what the Christian church believes about salvation; doubtless he has picked up on these things through his years as a member of the church and as a student in religious studies programs both at the undergraduate and graduate levels. We, like Turk, desire for Chris to know Jesus as his savior—Chris knows that full well. But to see the gospel tacked on the end of a Bible-brandishing diatribe in which the author takes jabs at both Chris’s sexuality and his body art comes across as condescending.

You see: you

say you want Chris (for example) to know Christ, but because he has rejected Christ – and ask him, because he has – you are willing to settle for a lot less in his case. That doesn’t actually have anything to do with what the church might do: that has to do with your uneasiness with the actual Christian message. And to make sure I tie that back to you previous statements, you have utterly forgotten that

historically the church does both, and that's how the West in particular has changed so much for the better in the last 1000 years.

What interests me is the characterization of my post as a "bible-brandishing diatribe" in order to again score point. If you would be so kind as to indicate how many verses of the Bible I cited to make my points to Chris, I would be glad to retract all of them – but again, I think this falls into the category of you personally not actually reading my open letter, and therefore not actually responding to what I wrote. There are no direct references to the Bible in my original open letter, and you ought to have seen that immediately.

The final irony, of course, is that you resort in your final arc of reasoning to a little Bible-brandishing of your own:

The Bible states in 1 Peter 3:15:

"But in your hearts revere Christ as Lord. Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect"

We’d like to suggest that the conversation of interfaith cooperation – the precise conversation that Chris Stedman indeed does work to shape – presents a better opportunity for giving that answer mentioned in 1 Peter than the method observed in Turk’s "open letter." Ironically, this verse can be found on one of the "Pyromaniacs" logos plastered all over their site. Yet it seems they’ve forgotten this respect in their determination to criticize our friend and wave the gospel in his face.

This is an interesting way to put this, since you have already decried any "giving an answer" in your sociological approach. You could go to any of the examples I have reaised so far and consider it in the light of what you say here and find yourself in a very challenging position: how do I advocate for the

Christian solution to this problem, when I am already committed to making sure I do not bring into consideration the personal ethics of the people I am talking to?

And this is the greatest challenge to your attempt at a rebuke here which you simply do not see: you call yourselves "Evangelicals". In your defense, that title doesn’t really mean anything today except "sociologically-Christian," so Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses and all manner of post-Christian cults might be rolled up under that umbrella. But the title "Evangelical" actually has a meaning in reference to one’s theology as it was historically understood. According to Wikipedia, this term means:

Evangelicalism is a Protestant Christian movement which began in Great Britain in the 1730s. Its key commitments are:

- The need for personal conversion (or being "born again")

- Actively expressing and sharing the gospel

- A high regard for biblical authority, especially biblical inerrancy

- An emphasis on teachings that proclaim the death and resurrection of Jesus

David Bebbington has termed these four distinctive aspects conversionism, activism, biblicism, and crucicentrism, noting, "Together they form a quadrilateral of priorities that is the basis of Evangelicalism."

And this, really, lies as the foundation of all your other problems. You self-identify with "Evangelicalism" and call yourselves "Evangelicals", but you are no such thing. An "evangelical" thinks proclaiming the Gospel is of the highest priority; you think it is a hopeful secondary objective. An "Evangelical" has a high regard for inerrancy and Biblical authority; you believe that the Bible’s authority is as one source of information in the secular context. An "Evangelical" thinks that teaching what the death and resurrection of Jesus means is a key emphasis; for you, it hasn’t yet come up – and can’t, because it will offend the personal ethics of those you would have to tell it to. You assume they have heard it and that is enough. Finally, an "Evangelical" places the conversion of others to being followers of Christ – not just admirers or glib flatterers of Christ – as the key objective of the Christian faith; for you, playing well with others is the key objective, and if that objective means they don’t hear the Gospel or respond to it, there’s always tomorrow.

With all that said, WORD says I have waterfalled over 9 pages in response to you – which I think is more than adequate. That’s 3X what I usually limit myself to for a Wednesday blog post. I have addressed your concerns line by line, and have added my own points of contention with your approach, theology, and objectives.

What I will leave you with, then, is this: If what you want is a secular, sociological philosophy which fosters pluralism and only focuses on doing good deeds on the largest scale without reference to any specific epistemology for knowing what is right and wrong except that we are "better together", I’ll be grateful for you to do that. I’ll be pleased that someone has found for themselves a goal they think is worth spending their life on. But there are three things I cannot do with that:

1. I cannot pretend that when you advocate for that, and need to suspend the use of truth to do so, you haven’t done anything wrong. There are probably humanist reasons I could advocate for here, but I’m not a Humanist. As a Christian, I am offended (but not surprised) that the first line of reproach against me is to tell the world something false about what I have done.

2. I cannot pretend that your version of what you say you mean to do is better than what has come before it. At least the old main-line Liberal approach stood in the Sermon on the Mount and in Leviticus and looked for the longest possible list of good works to produce rather than to a reductive consensus which everyone can agree on. Your version compared to your intellectual fathers is not even compelling in terms of what it is seeking to accomplish.

3. I cannot pretend that what you are advocating for here is "Evangelical" – unless we change the meaning of the word to be "something people who grew up in church call themselves".

If that further offends you, so be it. But in that, I offer you the chance to repent of your mistakes. The real message of Jesus is that when we turn away from what God has actually said to what seems right in our own eyes, we can repent if we believe that Christ died for our sins and was raised to new life to prove his work was worthy.

This is your chance to repent, if you believe. You can repent of abusing facts to advocate for social ends; you can repent of neglecting evangelism for the sake of making more friends; you can repent of denigrating the authority of the Bible; you can repent of making Jesus into merely a good example.

And I call you to it. I am travelling on business this week, so my availability to moderate the comments here and respond further is severely limited. I am leaving the comments open only for the sake of fostering further actual dialog here, but if they get out of hand I am sure Dan and Phil will shut them down. However, if you want to discuss this further in another forum, my e-mail address, as always, is

frank@iturk.com. My thanks for your time and consideration.

Kregel has been putting out some great books, of which three in recent years have been this one and this one and this one. Wellsir (and ma'am), they're inviting interested and qualified bloggers to apply to become Kregel bloggers and participate in blog tours as part of introducing new books. Kregel has significant, interesting, solid titles coming out in each catalog.

Kregel has been putting out some great books, of which three in recent years have been this one and this one and this one. Wellsir (and ma'am), they're inviting interested and qualified bloggers to apply to become Kregel bloggers and participate in blog tours as part of introducing new books. Kregel has significant, interesting, solid titles coming out in each catalog.

N October 1, 1861, Mr. Spurgeon gave, in the Tabernacle, a lecture which was destined to attract more public attention than any which he had previously delivered. It was entitled, "The Gorilla and the Land he Inhabits," and was largely concerned with

N October 1, 1861, Mr. Spurgeon gave, in the Tabernacle, a lecture which was destined to attract more public attention than any which he had previously delivered. It was entitled, "The Gorilla and the Land he Inhabits," and was largely concerned with  True, his claim to be our first cousin is disputed, on behalf of

True, his claim to be our first cousin is disputed, on behalf of  But who can deny that there is a likeness between this animal and our own race? . . . There is, we must confess, a wonderful resemblance,—so near that it is humiliating to us, and therefore, I hope, beneficial. But while there is such a humiliating likeness, what a difference there is! If there should ever be discovered an animal even more like man than this gorilla is; in fact, if there should be found the exact facsimile of man, but destitute of the living soul, the immortal spirit, we must still say that the distance between them is immeasurable. . . ."

But who can deny that there is a likeness between this animal and our own race? . . . There is, we must confess, a wonderful resemblance,—so near that it is humiliating to us, and therefore, I hope, beneficial. But while there is such a humiliating likeness, what a difference there is! If there should ever be discovered an animal even more like man than this gorilla is; in fact, if there should be found the exact facsimile of man, but destitute of the living soul, the immortal spirit, we must still say that the distance between them is immeasurable. . . ."

hy do so many evangelicals act as if false teachers in the church could never be a serious problem in this generation? Vast numbers seem convinced that they are "rich, have become wealthy, and have need of nothing'; and do not know that [they] are wretched, miserable, poor, blind, and naked" (Revelation 3:17).

hy do so many evangelicals act as if false teachers in the church could never be a serious problem in this generation? Vast numbers seem convinced that they are "rich, have become wealthy, and have need of nothing'; and do not know that [they] are wretched, miserable, poor, blind, and naked" (Revelation 3:17). In reality, the church today is quite possibly more susceptible to false teachers, doctrinal saboteurs, and spiritual terrorism than any other generation in church history. Biblical ignorance within the church may well be deeper and more widespread than at any other time since the Protestant Reformation. If you doubt that, compare the typical sermon of today with a randomly-chosen published sermon from any leading evangelical preacher prior to 1850. Also compare today's Christian literature with almost anything published by evangelical publishing houses a hundred years ago or more.

In reality, the church today is quite possibly more susceptible to false teachers, doctrinal saboteurs, and spiritual terrorism than any other generation in church history. Biblical ignorance within the church may well be deeper and more widespread than at any other time since the Protestant Reformation. If you doubt that, compare the typical sermon of today with a randomly-chosen published sermon from any leading evangelical preacher prior to 1850. Also compare today's Christian literature with almost anything published by evangelical publishing houses a hundred years ago or more.

O truth is more plainly taught in God’s word than this, that the salvation of sinners is entirely owing to the grace of God. If there be anything clear at all in Scripture, it is plainly there declared that men are lost by their own works, but saved through the free favor of God their ruin is justly merited, but their salvation is always the result of the unmerited mercy of God. In varied forms of expression, but with constant clearness and positiveness, this truth is over and over again declared.

O truth is more plainly taught in God’s word than this, that the salvation of sinners is entirely owing to the grace of God. If there be anything clear at all in Scripture, it is plainly there declared that men are lost by their own works, but saved through the free favor of God their ruin is justly merited, but their salvation is always the result of the unmerited mercy of God. In varied forms of expression, but with constant clearness and positiveness, this truth is over and over again declared.

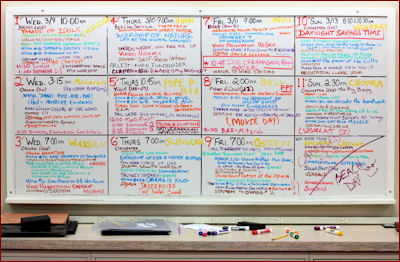

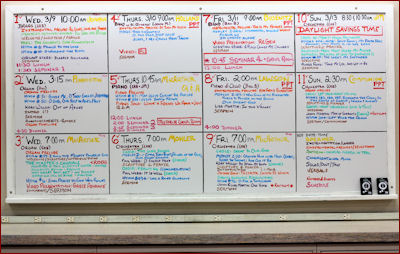

he music department at Grace Community Church used this white board to plan the order of service for each session of the Shepherds' Conference:

he music department at Grace Community Church used this white board to plan the order of service for each session of the Shepherds' Conference:

ere's what the white board looked like after some anonymous miscreant (a seminary student enjoying Spring Break, perhaps) used it to reimagine what "The Shepherds' Conversation" might look like if we had been prone to follow the evangelical drift of the past couple of decades:

ere's what the white board looked like after some anonymous miscreant (a seminary student enjoying Spring Break, perhaps) used it to reimagine what "The Shepherds' Conversation" might look like if we had been prone to follow the evangelical drift of the past couple of decades: