This is part of an ongoing (albeit sporadic) series related to 2 Corinthians 5:21. For previous posts in the series, see "The Key to the Gospel (With an Unexpected Addendum about My Criticism of NT Wright)"; "The Heart of the Gospel?"; and "Back Again."

n a previous post ("The Heart of the Gospel?") we discussed the historic and biblical importance of justification by faith and the principle of sola fide. It is to the shame and the detriment of the evangelical movement that we have not given this doctrine sufficient stress or suitable attention for the past century or more.

n a previous post ("The Heart of the Gospel?") we discussed the historic and biblical importance of justification by faith and the principle of sola fide. It is to the shame and the detriment of the evangelical movement that we have not given this doctrine sufficient stress or suitable attention for the past century or more.You'll discover an interesting irony if you study the history of the fundamentalist movement at the start of the 20th century: That movement almost from its inception failed to place sufficient stress on this most important of all fundamental doctrines.

The name fundamentalism is derived from a series of articles titled "The Fundamentals"—written in defense of several vital doctrines under attack from the modernists. It was a terrific set of tracts. They were not academic papers; they were apologetic arguments accessible to lay people. The complete set was ultimately published in book form (republished in four volumes in the 1990s). Most of the articles stand up quite well almost a century later.

But study the table of contents and you will notice a glaring omission: There is only one brief article in defense of the doctrine of justification by faith. It's a short and succinct article by H. C. G. Moule, then Bishop of Durham. It's fine, as far as it goes, but it stops short of being a thorough and definitive explanation of how Christ's righteousness is imputed to the sinner. It's buried in the middle of the third volume, not at all given the kind of prominence this doctrine deserves (and received from the Reformers and Puritans).

Perhaps our fundamentalist ancestors simply took the principle of sola fide for granted. It's true that the doctrine of justification was not the focus of the modernist attack. (The main 19th-century battle for justification by faith had come much earlier in response to the Oxford Movement.) So the doctrine of justification simply wasn't large on the radar screen in any of the battles the early fundamentalists were fighting.

Unfortunately, the same pattern of neglect continued for almost 100 years.

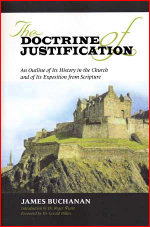

In 1961, the Banner of Truth Trust published a reprint of a book that was then 97 years old. The Doctrine of Justification, by James Buchanan, was originally published in 1867. The first Banner reprint in 1961 carried a Foreword by J. I. Packer in which Packer wrote this:

In 1961, the Banner of Truth Trust published a reprint of a book that was then 97 years old. The Doctrine of Justification, by James Buchanan, was originally published in 1867. The first Banner reprint in 1961 carried a Foreword by J. I. Packer in which Packer wrote this:It is a fact of ominous significance that Buchanan's classic volume, now a century old, is the most recent full-scale study of justification by faith that English-speaking Protestantism . . . has produced. If we may judge by the size of its literary output, there has never been an age of such feverish theological activity as the past hundred years; yet amid all its multifarious theological concerns it did not produce a single book of any size on the doctrine of justification. If all we knew of the church during the past century was that it had neglected the subject of justification in this way, we should already be in a position to conclude that this has been a century of religious apostasy and decline.It's been some 44 years since Packer wrote those words. And now the doctrine of justification by faith is under attack on several fronts within the evangelical movement. After multiple generations of near total silence on the subject, evangelicals are not well-equipped to defend sola fide.

The ecumenical movement represented by the "Evangelicals and Catholics Together" (ECT) document has made serious inroads into evangelical churches for precisely this reason: the inaccurate and watered-down notion most modern evangelicals have regarding justification by faith really isn't all that different from Medieval Roman Catholicism. The typical evangelical these days doesn't understand the doctrine of justification well enough to see how profound and important the difference is between what the Reformers taught and what the Roman Catholic Council of Trent declared. Try this if you don't believe me: Read the council of Trent on justification to the typical evangelical; don't tell him what it is; and in all likelihood, he will think it is perfectly sound.

In fact, that is pretty much what ECT implied, and what some evangelical leaders are now expressly saying: Luther and the Reformers got it wrong. Some actually claim that everyone since the time of Augustine has badly misunderstood what the apostle Paul meant when he spoke of justification by faith. Various New Perspectives on Paul and the doctrine of justification by faith have had a surprising and dismaying influence in Reformed circles, where you would expect men to understand and fight for the central, defining doctrine of the Protestant Reformation.

It seems to me that Paul's teaching on justification by faith is neither as obscure nor as difficult to follow as the new breed of New Testament scholarship wants to pretend. Romans 3-4, Romans 5, Romans 8, Philippians 3, and many other key texts on justification are as clear and definitive as anything in Scripture. Taken together, they give us an understanding of justification by faith that is the ideal anchor and the perfect centerpiece of a comprehensive biblical theology. It is my contention that proper exegesis of all the biblical texts will definitively prove the principles of sola fide, the imputation of Christ's righteousness, the forensic nature of justification, and every other key point that was under dispute in the Protestant Reformation.

But perhaps the best, most pointed, most explicit single text that sums up Paul's view of the evangelistic message most clearly is 2 Corinthians 5:21: "He hath made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him."

Starting next week (in a series of posts I have been planning and promising and hoping to get to for the past few months) we'll delve into that text and examine how Paul himself boiled evangelical truth down to its bare essence.

Addendum:

So as not to bury this post over the weekend, here, earlier than ever, is—

Your weekly dose of Spurgeon

The PyroManiacs devote space at the beginning of each week to highlights from The Spurgeon Archive. The excerpt that follows is from "The Heart of The Gospel," one of five sermons Spurgeon preached on 2 Corinthians 5:21. This message was delivered 18 July 1886 (a Sunday norning) at the Metropolitan Tabernacle:

The Most Fundamental of All the Fundamentals

The great doctrine, the greatest of all, is this, that God, seeing men to be lost by reason of their sin, hath taken that sin of theirs and laid it upon his only begotten Son, making him to be sin for us, even him who knew no sin; and that in consequence of this transference of sin he that believeth in Christ Jesus is made just and righteous, yea, is made to be the righteousness of God in Christ. Christ was made sin that sinners might be made righteousness. That is the doctrine of the substitution of our Lord Jesus Christ on the behalf of guilty men.

The great doctrine, the greatest of all, is this, that God, seeing men to be lost by reason of their sin, hath taken that sin of theirs and laid it upon his only begotten Son, making him to be sin for us, even him who knew no sin; and that in consequence of this transference of sin he that believeth in Christ Jesus is made just and righteous, yea, is made to be the righteousness of God in Christ. Christ was made sin that sinners might be made righteousness. That is the doctrine of the substitution of our Lord Jesus Christ on the behalf of guilty men.

40 comments:

After multiple generations of near total silence on the subject, evangelicals are not well-equipped to defend sola fide.

I do not take up your lament, since I think sola fide is not a doctrine worth defending. Notwithstanding that, I would, however, question what silence you are talking about. From my experience within Protestantism, I have read theology books that go out of their way to talk about it, heard preachers talk about it, (usually contrastng it with the RCC, and usually inaccurately) and other such avenues. Perhaps your experience has been different. In every evangelical church that I can remember attending I have heard sola fide stressed, exegeted, etc. But I suppose I can only speak for myself. Personally, I don't believe sola fide, so it's decline within modern protestantism and evangelicalism might not be a bad thing.

In fact, that is pretty much what ECT implied, and what some evangelical leaders are now expressly saying: Luther and the Reformers got it wrong.

Concerning sola fide- yes.

Some actually claim that everyone since the time of Augustine has badly misunderstood what the apostle Paul meant when he spoke of justification by faith.

I'm not sure what this is supposed to mean, since regarding sola fide Protestantism essentially claims the church has pretty much gotten it wrong since the apostles died. I do agree, however, that the reformed position misunderstands Paul quite a bit.

It is my contention that proper exegesis of all the biblical texts will definitively prove the principles of sola fide, the imputation of Christ's righteousness, the forensic nature of justification, and every other key point that was under dispute in the Protestant Reformation.

Since you are beginning with sola fide as your exegetical matrix, it seems quite impossible that you could possibly conclude anything different.

Phil, I look forward to your posts on this subject. 2 Cor 5:21 and Romans 4:4-5 leave no possibility other than righteousness freely given by grace through faith. Perhaps theologians haven't written as much about faith alone in recent years, but I would bet the pages of most folks' Bibles are well-thumbed in the area from the 3rd through the 5th chapters of Romans!

Bring it on! Looking forward to the continuation of this series.

Allister McGrath writes, “ It is a well known fact that, in the 1559 edition of this work, Calvin defers his discussion of justification until Book III, and it is then found only after a detailed exposition of sanctification. This has proved a serious embarrassment to those who project Luther’s concern with the articulus iustificationis on to Calvin, asserting that justification is the ‘focal centre’ of the Institution.” (Iustitia Dei, 225)

It's not an embarassment for me since Calvin himself writes at the beggining of that section of the Institutes that, "The theme of justifiaction was therefore more lightly touched upon because it was more to the point to understand first how little devoid of good works is the faith, through which alone we obtain free righteousness by the mercy of God; and what is the nature of the good works of the saints, with which part of this question is concerned. Therefore we must now discuss these matters thoroughly. And we must so discuss them as to bear in mind that this is the main hinge on which religion turns, so that we devote the greater attention to it. For unless you first of all grasp what your relationship to God is, and the nature of His judgment upon you, you have neither a foundation on which to establish your salvation nor one on which to build piety toward God."

Ad Fontes!

deviant

Well you outsmarted that Paul. He says it was not by works but by faith because no one is justified by works. But somehow you must have gotten some extra-biblical revelation that says the Bible is wrong. Through the Old Testament to the New Testament the emphasis is on faith, the key is faith, faith will produce good works but those good works don't justify us before God. Those good works will justify us in the eyes of other people, like James argued for. The church was getting the whole faith thing wrong when the apostles were alive, hence Paul arguing for justification by faith and imputation of righteousness.

Perhaps Sola Fide is being attacked in order to make us devote more theologocal attention to it.

I'm aware of Catholic doctrine but I hadn't read through the Council of Trent before. This is pretty heavy actually:

If any one saith, that by faith alone the impious is justified; in such wise as to mean, that nothing else is required to co-operate in order to the obtaining the grace of Justification, and that it is not in any way necessary, that he be prepared and disposed by the movement of his own will; let him be anathema.

How on earth can saying we are justifed by faith alone be deserving of anathema? It is so clearly stated in scripture as you point out Phil.

It seems to be about protecting the institution above conducting honest biblical enquiry to me (The Trent thing I mean).

... I think sola fide is not a doctrine worth defending

You have identified a line that separates the Biblical Gospel from all others, Deviant. But evidently you've parked yourself on the wrong side of the line. It's a losing side.

Deviant Monk wrote:

"I'm not sure what this is supposed to mean, since regarding sola fide Protestantism essentially claims the church has pretty much gotten it wrong since the apostles died."

You and Dr Stanley need to read (or reread in the case of Dr Stanley) one of the threads Phil linked to at the beginning of his post:

http://teampyro.blogspot.com/2006/05/heart-of-gospel.html

In that thread, some of the participants here give examples of sola fide in sources between the apostles and the Reformation. The issue of John Calvin's view was addressed as well.

There's no rational way to deny that a passage like Genesis 15:6 involves faith without any accompanying sacraments or works of other types. There's no reasonable way to deny that people are justified as soon as they believe in passages like Acts 10:44-48 and Galatians 3:2-9, without having to wait for any later participation in sacraments or works of some other type. Passages like the ones I just cited are treated as normative in scripture, so they can't be dismissed as exceptions to a rule. Sola fide is Biblical, it's patristic, and it's found in other pre-Reformation sources aside from the apostolic writers and the church fathers.

Let's get this party started!

Dr Stanley said:

"I just thought it was a little humourous that Phil viewed the doctrine being religated to the 'third volume' as a failure to recognize the importance after we already had the conversation in which everyone argued that Calvin's placement of the doctrine DID NOT indicate a failure to recognize the importance. The parallels were too much for me to not comment."

Phil didn't say that the placement of John Calvin's material or the placement of H.C.G. Moule's material was the only factor he was taking into account. He also mentioned other factors and contrasted the treatment of justification in The Fundamentals with its treatment in the reformers and the Puritans. Whatever similarities there are between the Calvin material and the Moule material, the point is that there are significant differences as well.

Dr. Stanley: "I just thought it was a little humourous that Phil viewed the doctrine being religated to the "third volume" as a failure to recognize the importance . . ."

The operative phrase in what I actually said was: "only one brief article."

The operative phrase in what Calvin actually said was "Justification . . . is the principal hinge on which all religion hangs, so it requires greater care and attention" (Institutes, 3.11.1). Although he started his discussion of justification in vol. 3, he expressly said that he regarded everyting prior to that as the prelude to his treatment of justification.

Read what Calvin wrote about justification in chapters 11-18 of vol. 3, and then tell me if you seriously are going to argue that he deemed it less than essential.

Phil,

Good stuff. Just one thing....

In 1961, the Banner of Truth Trust published a reprint of a book that was then 97 years old. The Doctrine of Justification, by James Buchanan, was originally published in 1867. The first Banner reprint in 1961...

This would be 94 years, not 97. Either that or it was published in 1864 not 1867. Just keeping it real for the homeschool moms.

Brad

steve-

Well you outsmarted that Paul. He says it was not by works but by faith because no one is justified by works. But somehow you must have gotten some extra-biblical revelation that says the Bible is wrong.

??? I don't quite understand this comment. I don't recall saying that the bible was wrong. Please show me where I said so. I said the Reformed position misunderstands Paul quite a bit. I fail to see how this equates to saying the Bible is wrong.

Perhaps by your saying I think the bible is wrong, you actually mean I think what you think the bible says is wrong, which I do.

I don't believe that Paul equates 'works' with action. Rather, Paul sees 'works' as those things inherent within the Jewish system by which the Jews believed themselves to be justified, and by which they felt the Gentiles must adhere to be justified. This is the point of Paul's whole argument about Abraham- it wasn't that Abraham didn't do anything, but rather that Abraham was justified before being identified through the Jewish cultus. If Paul meant 'action', his entire argument in relation to circumcision is entirely superfluous, and completely contradictory to James.

James is even more explicit than Paul and says without equivocation that "a person is justified by what he does and not by sola fide."

Through the Old Testament to the New Testament the emphasis is on faith, the key is faith, faith will produce good works but those good works don't justify us before God. Those good works will justify us in the eyes of other people, like James argued for. The church was getting the whole faith thing wrong when the apostles were alive, hence Paul arguing for justification by faith and imputation of righteousness.

How is James talking about good works justifying us in the eyes of other people? James is talking explicitly about Abraham being justified before God because of what he did.

In regards to the church getting faith wrong, and Paul needing to correct them- as can be seen from the issues raised at the council of Jerusalem, Paul's argument about the Jewish cultus having no justifying merit in Romans, and the confrontation with Peter in Galatians, the issue is not about imputation of righteousness from faith alone but rather trying to receive or complete justification through the Jewish cultus.

phil-

You have identified a line that separates the Biblical Gospel from all others, Deviant. But evidently you've parked yourself on the wrong side of the line. It's a losing side.

Why am I necessarily on the losing side? I can appeal to the scriptures just as much as you can, so I think what I believe is biblical, as well as within the historical understanding of the church universal.

I would assume you would hold to sola scriptura- then how could you possibly make such a determination, if I can appeal to the scriptures as much as you?

jason-

You and Dr Stanley need to read (or reread in the case of Dr Stanley) one of the threads Phil linked to at the beginning of his post:

http://teampyro.blogspot.com/2006/05/heart-of-gospel.html

In that thread, some of the participants here give examples of sola fide in sources between the apostles and the Reformation. The issue of John Calvin's view was addressed as well.

First off- it's extremely poor form to ask somebody to sift through a previous post, especially to find the answers within the comments. However, I found the list, and still find it very lacking.

I disagree that sola fide is patristic. From the writings of the church fathers that I have read, (most of the ante-nicene fathers, augustine, chrysostom, athanasius) none of them approach the protestant understanding of sola fide. In church history classes I have taken and historical theology books I have read, the point is made that sola fide was not the predominant understanding of justification. In fact, before I stopped affirming sola fide I was distressed in my reading that the early church fathers seemed to either know nothing of it or flatly contradicted it.

No orthodox segment of Christianity has denied that we are justified by faith. But justificaton by faith does not equal sola fide. Catholics and orthodox believe that faith is a part of justification. The list I saw of tertullian and others said that they taught justification by faith- I'm sure they did, but that does not mean they taught sola fide.

There's no rational way to deny that a passage like Genesis 15:6 involves faith without any accompanying sacraments or works of other types.

James certainly seems to disagree with you.

There's no reasonable way to deny that people are justified as soon as they believe in passages like Acts 10:44-48 and Galatians 3:2-9, without having to wait for any later participation in sacraments or works of some other type. Passages like the ones I just cited are treated as normative in scripture, so they can't be dismissed as exceptions to a rule.

1. Even within RCC theology the sacrament of baptism is in some cases not absolutely necessary.

2. That Acts 10:44-48 is 'normative' seems questionable, since the entire scenario is the out-of-the-ordinary experience that convinces Peter of God's acceptance of the Gentiles, and aids in the decision that the gentiles do not need to be circumcised. That being said, baptism seems to be the normative in the NT, as Paul talks about it in connection with justification in Romans 6, and how Peter calls the crowds to repent and be baptized and even says it is what saves in 1 Peter.

Sola fide is Biblical, it's patristic, and it's found in other pre-Reformation sources aside from the apostolic writers and the church fathers.

If sola fide is biblical, then James should be chucked, since he explcitly contradicts it.

I have an idea.

deviant monk:

Rather than see you get dog-piled here, I'd like to give you the opportunity to substantiate your claim that "sola fide is not a doctrine worth defending".

I have a nice little blog called Ask the Calvinist in which I get to ask you questions about your opinion, you get to answer, and then you get to ask me a question, and I get to answer it -- without a lot of piling on or distractions. You can read the basic guidlines in the sidebar there.

If you are interested in bringing your dismissal of sola fide into the sunlight, I welcome your participation. Please e-mail me (my e-mail in in my blogger profile) if you are interested.

If you'd rather defend your opinion here, good luck with that.

One thing about the book of James before I run off to church.

I always enjoy reading people who say, "that durn James certainly doesn't say we are justified by faith, so ..." and then insert their theological opinion about the rest of the NT based on what James obviously said.

What your particular reading of James overlooks, DM, is that the letter begins thus:

Count it all joy, my brothers, when you meet trials of various kinds, for you know that the testing of your faith produces steadfastness. And let steadfastness have its full effect, that you may be perfect and complete, lacking in nothing.

Isn't that interesting? James here makes the foundational statement for his letter the assumption that faith produces works.

In that, whatever it is exactly you want to read into what we call chapter 2 of this book, it has to confoirm with James' assumption that "steadfastness" is a result of faith.

I'm not a big fan of the "justified before people" reading of James 2, but your objection to it doesn't actually address the kind of argument James has made here -- which is plainly that if you have faith, you will have works which are a result of that faith.

And again, if you want to has that out, I have a nice quiet place in which to do that.

Oh boy -- another pet peeve:

from 1Pet 3:

Baptism, which corresponds to this, now saves you, not as a removal of dirt from the body but as an appeal to God for a good conscience, through the resurrection of Jesus Christ, who has gone into heaven and is at the right hand of God, with angels, authorities, and powers having been subjected to him.

There are a lot of people who will tell you, "I doin't even think this passage is talking about water baptism," but they are simply wrong. However, to say that this passage blankly makes baptism the operator for salvation is also simply wrong.

You can see this if you find the antecendent to "to this". I challenge you to find it and then make that information fit back into your glib interpretation of the passage as you have provided it so far.

Deviant Monk said:

"This is the point of Paul's whole argument about Abraham- it wasn't that Abraham didn't do anything, but rather that Abraham was justified before being identified through the Jewish cultus. If Paul meant 'action', his entire argument in relation to circumcision is entirely superfluous, and completely contradictory to James....In regards to the church getting faith wrong, and Paul needing to correct them- as can be seen from the issues raised at the council of Jerusalem, Paul's argument about the Jewish cultus having no justifying merit in Romans, and the confrontation with Peter in Galatians, the issue is not about imputation of righteousness from faith alone but rather trying to receive or complete justification through the Jewish cultus."

Paul doesn't just exclude one system of works. He excludes every conceivable system of works, and he does so in more than one way. In Romans 3:27, he contrasts a law of faith with any law of works. To read Romans 3:27 as a reference to a Jewish system of works, without any intention of excluding other systems of work, would be implausible. The alternative Paul offers is "faith", not "faith and a non-Jewish system of works". Similarly, Paul tells us in Galatians 3:21-25 that there isn't any system of works whereby we can attain justification. No conditions can be added to what God has offered (Galatians 3:15). Paul doesn't limit himself to one system of works, as if adding circumcision to faith would be unacceptable, whereas adding tithing or church attendance would be acceptable. So, your argument is fallacious in light of Paul's exclusion of every system of works, not just one Jewish system.

Secondly, your argument is untenable in light of Paul's inclusion of nothing other than faith. As I said with regard to Romans 3:27, the alternative Paul offers is faith, not faith and something else. To argue that Paul meant to imply the inclusion of something else, but didn't mention it, in dozens of passages in which he only mentions faith is implausible.

Third, we know that your argument is false because of Paul's use of Genesis 15:6. In that passage, Abraham only believes (sola fide). Not only is circumcision absent, but so are baptism, tithing, honoring of parents, submission to government authorities, church attendance, and every other conceivable good work.

Fourth, we can compare your view to the Biblical examples of the justification of various individuals. In Galatians 3:2-9, for example, a passage I cited in my last response to you, Paul refers to the Galatians' being justified when they believed the word being spoken. They weren't justified when they were baptized or when they did some other good work. Rather, they were justified as soon as they believed. Paul goes on to cite Genesis 15:6 as an illustration again, and Genesis 15:6 most surely does not illustrate baptismal justification or any other form of justification through works. What it illustrates is sola fide. Similarly, every other example of how people were justified, without exception, has people being justified upon faith, prior to baptism and other works (Mark 2:5, Luke 7:50, 18:10-14, etc.). Given that we have all of these Biblical examples of people being justified prior to doing any good works, and given that we have no examples of a person coming to faith and having to wait until baptism or some other later work before being justified, it seems unlikely that all of these Biblical examples of sola fide are exceptions to a rule.

Your view also gives us a weaker explanation for the Biblical passages that refer to eternal life as a free gift. You would affirm that the opportunity to work for eternal life is free, but eternal life itself is not free under your system. Similarly, your view gives us a weaker explanation of the substitutionary nature of Christ's work. A passage like 1 Corinthians 2:2 or Galatians 6:14 makes far more sense under sola fide than it does under any system that combines faith and works.

You wrote:

"First off- it's extremely poor form to ask somebody to sift through a previous post, especially to find the answers within the comments."

No, it's not "extremely poor form" for me to tell you where you can find further documentation. I gave you some examples of my evidence, such as Acts 10 and Galatians 3, but I didn't repeat everything I argued in the other thread. Why is it "extremely poor form" for me to give you some representative examples of my evidence, then point you to a thread in which I've gone into more detail? That thread is part of Phil Johnson's series, so reading it would help you understand this post better anyway. If you don't want to take the time to read the other thread, then say so, but I don't think I've shown "extremely poor form" by suggesting that you read it.

You wrote:

"I disagree that sola fide is patristic. From the writings of the church fathers that I have read, (most of the ante-nicene fathers, augustine, chrysostom, athanasius) none of them approach the protestant understanding of sola fide. In church history classes I have taken and historical theology books I have read, the point is made that sola fide was not the predominant understanding of justification. In fact, before I stopped affirming sola fide I was distressed in my reading that the early church fathers seemed to either know nothing of it or flatly contradicted it."

There's a difference between "not the predominant understanding" and "either know nothing of it or flatly contradicted it". I would agree with you that sola fide was a minority view. But I reject your suggestion that it's absent from all of the church fathers. And the fathers weren't the only Christians who lived between the apostles and the Reformation.

I don't know what history classes you took or what theology books you read, but different scholars take different positions on this issue. In the previous thread I linked you to, I and other posters give examples of scholars who think that sola fide is found in some sources between the apostles and the Reformation.

As I said above, the church fathers weren't the only Christians who lived during the time in question. Some of the church fathers argued against people in their day who believed in justification apart from baptism or who taught that works in general aren't a means of attaining justification. If those fathers rejected sola fide, then what was the position of the people they were arguing against? Are you going to claim that the people they were arguing against rejected sola fide also? If so, then what were these people being criticized for? If you think that they did advocate sola fide, then they would be examples of people who held that view between the time of the apostles and the Reformation. I see no reasonable way to deny that some people held sola fide during that timeframe. The quantity of people who did so is more questionable, but the concept that nobody held the view seems to me to be implausible.

You wrote:

"The list I saw of tertullian and others said that they taught justification by faith- I'm sure they did, but that does not mean they taught sola fide."

I don't know what "list" you're referring to, but I discussed Tertullian in the context of some people he wrote against. He was opposing some people in his day who advocated justification through faith alone, apart from baptism. If you're referring to what I wrote about Tertullian, then you might have misunderstood what you were reading.

You wrote:

"Even within RCC theology the sacrament of baptism is in some cases not absolutely necessary."

The primary issue here is what's normative, not exceptions to a rule. If a passage of scripture teaches justification through faith alone in a normative context, it would make no sense to appeal to exceptional cases in Roman Catholic theology in order to explain that passage.

You wrote:

"That Acts 10:44-48 is 'normative' seems questionable, since the entire scenario is the out-of-the-ordinary experience that convinces Peter of God's acceptance of the Gentiles, and aids in the decision that the gentiles do not need to be circumcised."

On the normative nature of Acts 10, see Peter's comments in Acts 15:7-11. Peter cites the people of Acts 10 as representative of how all people are justified. He doesn't just cite them to illustrate that Gentiles can be justified. He also cites them to illustrate that justification occurs through an instrument in the heart (Acts 15:8-9), which would exclude baptism and all other outward actions. If the Gentiles in Acts 10 had received the Holy Spirit after being baptized or after doing some other good work, that also would have demonstrated that Gentiles can be justified. Their justification prior to baptism wasn't necessary for illustrating the acceptance of Gentiles. Yet, God justified them prior to baptism. That's what we see over and over again in scripture (Genesis 15:6, Mark 2:5, Luke 7:50, 18:10-14, 23:39-43, Galatians 3:2-9, Ephesians 1:13-14, etc.). That's why Paul, in Acts 19:2, expected people to receive the Holy Spirit at the time of belief, not at the time of baptism. The people in Acts 19 were unusual in the manner in which they did receive the Spirit. They received the Spirit through the laying on of hands, not through faith (Acts 19:6). But Acts 19:2 demonstrates that Paul considered it normative to receive the Spirit, the seal of justification (Romans 8:9-11, Galatians 4:6, Ephesians 1:13-14), at the time of faith. The method of justification in Acts 10 is treated as normative in Acts 15, and it's consistent with how we see other people justified elsewhere in scripture. Why, then, should we think that Acts 10 is an exception to a rule?

You wrote:

"That being said, baptism seems to be the normative in the NT, as Paul talks about it in connection with justification in Romans 6, and how Peter calls the crowds to repent and be baptized and even says it is what saves in 1 Peter."

What connection does Romans 6 have with justification? Baptism is related to justification, in the sense that it results from justification and illustrates that justification, but nothing in Romans 6 logically leads to the conclusion that baptism is a normative means of attaining justification. Baptism does associate us with the death and resurrection of Jesus, but so do other activities in the Christian life (2 Corinthians 4:10-11, Philippians 3:10-12). In a passage like Romans 13:14, Paul can tell people who are already Christians to "put on the Lord Jesus Christ", since there are many things in the Christian life that can bind us to Christ, associate us with Him, make us more like Him, etc. To single out the passages on baptism, and assume that our association with Christ in baptism must be a matter of attaining justification, is insupportable from the text and contradicts many other texts.

With regard to 1 Peter 3:21, I recommend reading J.P. Holding's comments on the passage:

http://www.tektonics.org/af/baptismneed.html#1pt3

The context of 1 Peter 3 is a context primarily about sanctification. He's addressing Christians who are going through some difficulties. Baptism saved them in much the same way that bearing children saves women in a non-justifying sense (1 Timothy 2:15). The term "saved" is used in different ways in different contexts. The public pledge involved in baptism was sustaining these Christians in their trials. It was a means of sanctification. To read 1 Peter 3:21 as a reference to attaining justification through baptism would be unnatural in the context of the passage and would make it contradictory to what Peter and other Biblical authors said elsewhere.

You mention the book of James a lot, but you don't offer us any refutation of the common Protestant explanations of the text. James is wisdom literature. It uses brevity and figures of speech in much the same way that a book like Proverbs does. In chapter 2, James is addressing both the fact that true faith results in works and the fact that we can't show other people our faith without works. Works justify both in the sense of vindicating our claim to have faith (Luke 7:35) and in the sense of showing our faith to other people. We know that James was concerned with showing our faith to others, since he mentions the concept (James 2:18). The reason why he can mention both Genesis 15 and Genesis 22 in James 2:21-23 is because Abraham's justification in Genesis 15 is vindicated in Genesis 22. To interpret James as saying that Abraham was justified in the sense of attaining eternal life in both passages would be nonsensical. For one thing, Genesis 15 doesn't involve any works of any type, so there's no way to fit that passage into your system. Secondly, nothing happened in Abraham's life between Genesis 15 and Genesis 22 that would lead us to the conclusion that he needed to attain eternal life over again or needed to increase in that attainment (as if such a thing were possible). Third, the view that Abraham was working to attain eternal life in Genesis 22 would contradict many passages of scripture, such as the ones I've discussed above. Fourth, James distances himself from your view before he even begins the passage we're discussing. In James 2:10-13, we read that only perfection is acceptable before God. If you disobey in one area, you're guilty of all. We either attain eternal life through our perfection or attain it through the perfection of a substitute, namely Christ. James and scripture in general know nothing of your in-between system in which we attain eternal life through a combination of Christ's work and our imperfect obedience to God's commandments.

The concept of people coming to faith in Christ, yet having to wait until the ceremony of baptism an hour, a week, or a few months later before being justified, is anti-Biblical. The gospel is "Your faith has saved you; go in peace." (Luke 7:50)

Hey all,

Has anyone read James White's book on justification by faith?

I wondered how it related to the other book mentioned among other things, and wondered how it would weigh in on this conversation.

SDG,

DBH

Brad,

Thank you for your sensitivity towards the homeschool moms.

And I think the award for the longest comment on another person's blog now gets passed to Jason Engwer... scroll, scroll, scroll...

Interesting. Sola Fide is definitely worth defending and I am one that is ill-equipped to do it properly. I have tried and got hammered to the point of realizing that, well, I need to do more worthwhile studying on this.

David,

Read White's book for Theology II, it is really helpful to have a grasp on Greek when reading it becuase White loves to exegete straight from the Greek text in it. It seemed solid theologically.

Deviant,

Glad you had a talk with Paul and found out that he believes works are something different from what everyone else does. Paul does well in specifying the works of the law and works in general. But then again N.T. Wright whom I assume you get your theology from would disagree with that.

Deviant Monk: Your position isn't helped by your tendency to respond to things you obviously haven't bothered to read carefully. For instance, you replied to something DJP wrote and addressed your reply to me as if I had written it. Your anecdotal account of patristic history suffers from exactly the same kind of fault, as Jason has shown.

Jason: Good response. Thanks.

David Hewitt: James White, R.C. Sproul, and a few others have written some excellent material on justification in the past decade or so.

The Packer quotation is from the '60s. He pointed out then that no one had written anything significant on justification for almost a hundred years. It was almost 25 years more before much significant attention was paid to the doctrine. By then there was already a fairly large contingent of Reformed and evangelicals who were saying they didn't see what the big deal about sola fide is.

For anyone who seriously doesn't get the point, note the tone of some of the above comments, from ostensibly Protestant sources. I suppose it's not at all surprising that after a century of neglect, there's not much respect for (or understanding of) the material principle of the Reformation.

But compare the smart-aleck and dismissive attitude of those comments with the opening words of A. A. Hodge's chapter on justification in his handbook of doctrine for lay people titled A Brief Compend of Bible Truth:

"Correct ideas on the subject of a sinner's justification are exceedingly important; because this is a cardinal point in the Christian system. A mistake here will be apt to extend its pernicious influence to every other important doctrine."

Phil,

Another good (and needed) post.

Jason,

Good responses. You wrote: "Your view also gives us a weaker explanation for the Biblical passages that refer to eternal life as a free gift."

Especially Romans 4:4, where Paul states that if you get something for your works, it is not a gift, but what you earned. Then in v.5 he states "And to the one who does not work but trusts him who justifies the ungodly, his faith is counted as righteousness."(ESV)

So works to Paul are anything that earns something, and faith is not faithfulness, but trust/belief.

4given,

I've seen longer comments, but Jason's is in the top ten.

"... because we are justified by faith, we are, through faith, endowed with all the privileges and supplied with all the graces of the children of God." - Benjamin B. Warfield

" ... we should remember that in Christ we are justified. We are righteous in Him. ... we stand before God--clothed in the imputed righteousness of Jesus Christ." - Jerry Bridges

This is such a magnificient truth. It should bring tears of joy. And it surely does.

jason--

Paul doesn't just exclude one system of works. He excludes every conceivable system of works, and he does so in more than one way.

And so he should. However, the point Deviant Monk is making is that Prostestantism has created an unnecessary, unnatural and, IMO, unbiblical bifurction between “faith” and “action.” None of the orthordox church believes that we are justified because we belong to the cultus of a particular religion (which is the basis of Paul’s polemic against the “works” of the Judaizers). All orthodox Christians affirm that we are saved by the grace of God.

So the issue is not whether or not we are saved by “works” (as in the Judaizer’s belief system); the answer is obviously no. However, this answer does not mean that “faith” is bifurcated from “action.” As DM pointed out, the very example of Abraham which Paul conjures in Romans 4 proves that Paul clearly has an integrated view of “faith” in mind, not the dichotomous conception of “mental assent” that is separated from action.

In Romans 3:27, he contrasts a law of faith with any law of works. To read Romans 3:27 as a reference to a Jewish system of works, without any intention of excluding other systems of work, would be implausible.

Actually, the implausible interpretation is to go beyond Paul’s polemic against the Jewish system and to equate Paul’s language about “works” with “action” in an unqualified sense. Nonetheless, even if we pursue your contention, the answer will still be the same, and your bifurcation “faith” and “action” will reveal itself to be entirely artificial to the meaning of the text (precisely because you have gone beyond the context of the text and attempt to make universal propositional statements from Paul’s arguments).

The alternative Paul offers is "faith", not "faith and a non-Jewish system of works".

No one disagrees. However, the “faith” Paul offers is equally not “faith” but not “action.” As I have said before, your misunderstanding and misapplication of Paul’s polemic against the works of the Judaizers has led you to create an unnecessary and inappropriate dichotomy between “faith” and “action.”

Similarly, Paul tells us in Galatians 3:21-25 that there isn't any system of works whereby we can attain justification. No conditions can be added to what God has offered (Galatians 3:15). Paul doesn't limit himself to one system of works, as if adding circumcision to faith would be unacceptable, whereas adding tithing or church attendance would be acceptable. So, your argument is fallacious in light of Paul's exclusion of every system of works, not just one Jewish system.

It is not fallacious at all, as even the speculative expansion of “works” to other systems does not create a dichotomy between faith and action. No one is suggesting that one “system” be replaced with another. Rather, the argument that is being presented is merely intended to recapture the biblical conception of faith as the integration of belief and action.

Secondly, your argument is untenable in light of Paul's inclusion of nothing other than faith. As I said with regard to Romans 3:27, the alternative Paul offers is faith, not faith and something else. To argue that Paul meant to imply the inclusion of something else, but didn't mention it, in dozens of passages in which he only mentions faith is implausible.

This is only a necessary conclusion if one artificially bifurcates faith from action. As there is no reason in the biblical literature or historical theology to do so (and even better reason not to!), I would suggest that your rejection of what is being presented by Deviant is the rejection of a strawman which you have created.

Third, we know that your argument is false because of Paul's use of Genesis 15:6. In that passage, Abraham only believes (sola fide). Not only is circumcision absent, but so are baptism, tithing, honoring of parents, submission to government authorities, church attendance, and every other conceivable good work.

Read the whole story of Abraham. How does the narrative describe his “faith?” It is action! God told Abraham to go. What did Abraham do? Did he say, “Ah, I mentally assent in belief to what God has said?” No! He packed his family up and left. When God said to kill Isaac, Abraham took Isaac to the mountain and plunged the knife. The bottom line is that belief and action cannot not separated. One believes that which one does, and one does that which one believes. There is no logical or chronological relationship; rather, they are an integrated reality which the Scriptures refer to as “faith.” Belief without action and action without belief is not faith, for neither can exist without the other. Therefore, to say that one is justified by “faith” alone with the Protestant refusal of “action” is simply absurd and completely misunderstands the biblical and historical teaching about faith.

Fourth, we can compare your view to the Biblical examples of the justification of various individuals. In Galatians 3:2-9, for example, a passage I cited in my last response to you, Paul refers to the Galatians' being justified when they believed the word being spoken. They weren't justified when they were baptized or when they did some other good work.

Rather, they were justified as soon as they believed. Paul goes on to cite Genesis 15:6 as an illustration again, and Genesis 15:6 most surely does not illustrate baptismal justification or any other form of justification through works. What it illustrates is sola fide. Similarly, every other example of how people were justified, without exception, has people being justified upon faith, prior to baptism and other works (Mark 2:5, Luke 7:50, 18:10-14, etc.). Given that we have all of these Biblical examples of people being justified prior to doing any good works, and given that we have no examples of a person coming to faith and having to wait until baptism or some other later work before being justified, it seems unlikely that all of these Biblical examples of sola fide are exceptions to a rule.

Again, your conception proceeds from a misunderstanding of the meaning of “works” in Paul’s thinking. As DM pointed out, Paul’s polemic against “works of the law” is directed against the Judaizers who taught that Gentiles must become associated with a particular religious cultus before they could be justified with God. Paul, however, refuses this argument, claiming that all are justified apart from identification with a particular religious cultus (i.e., Abraham and circumcision) through faith. When he says this, however, he is NOT saying that action is alien or unnecessary to “faith.” All he is saying is that the path to God does not require identification and initiation into the Jewish (or another) system of ritual law. Therefore, I will very firmly affirm that we are justified not by works; nonetheless, this does not mean that faith can be divorced from action. Matthew 25 makes this abundantly clear. Of course, Jesus often doesn’t get much of a say in regards to the issue of justification by faith, so perhaps this is an irrelevant notation...

Your view also gives us a weaker explanation for the Biblical passages that refer to eternal life as a free gift. You would affirm that the opportunity to work for eternal life is free, but eternal life itself is not free under your system. Similarly, your view gives us a weaker explanation of the substitutionary nature of Christ's work. A passage like 1 Corinthians 2:2 or Galatians 6:14 makes far more sense under sola fide than it does under any system that combines faith and works.

A “weaker” explanation? Huh? Who defines that which is “weaker?” To my mind, a conception of “faith” which bifurcates “belief” and “action” is the most watered-down, hollow and disingenuous description which one could give. No one is advocating that we have to “work” for eternal salvation; nonetheless, this affirmation does not in any way necessitate a bifurcation of “belief” and “action.”

There's a difference between "not the predominant understanding" and "either know nothing of it or flatly contradicted it". I would agree with you that sola fide was a minority view. But I reject your suggestion that it's absent from all of the church fathers. And the fathers weren't the only Christians who lived between the apostles and the Reformation.

Well, the last statement is true. However, considering that their works are the ones that the historic church chose to preserve and considered relatively authoritative in terms of orthodox belief, an argument from silence on this issue is hardly compelling and appears, to be perfectly honest, somewhat desperate. Rather than using the Reformation to marginalize historical theology (which you admit did not affirm sola fidei in the majority), perhaps we should use the tradition which we have received to critique our beliefs. Just a suggestion...

I don't know what history classes you took or what theology books you read, but different scholars take different positions on this issue. In the previous thread I linked you to, I and other posters give examples of scholars who think that sola fide is found in some sources between the apostles and the Reformation.

But the indentification of “some” sources is not good enough. First of all, there is a very good chance that the quotations are incidental, rather than foundational to the writers’ thinking (and this is a reasonable conclusion, given your own admission about the “majority” view). Secondly, as Deviant pointed out, the identification of “some” sources does not suggest a comprehensive system of thought. Finally, as you will hopefully agree, all scholars are motivated by certain theological loyalties to come to particular conclusions about the nature and shape of historical theology. However, I would suspect that even the scholars to whom you would appeal would be forthcoming enough to admit that despite the ability to proof-text sola fidei out of historical theology, the evidence is overwhelming enough to conclude (even as you have admitted), that the majority view did not hold to this conception. Therefore, given this conclusion, and coupled with the fact that the historical church never codified sola fidei as an orthodox belief, Protestant theology must be very careful about how forcefully it teaches this concept, lest it (as in many other theological conclusions) effectively marginalize the very tradition to which it attempts to appeal in substantiating its presupposed theological understanding.

As I said above, the church fathers weren't the only Christians who lived during the time in question. Some of the church fathers argued against people in their day who believed in justification apart from baptism or who taught that works in general aren't a means of attaining justification. If those fathers rejected sola fide, then what was the position of the people they were arguing against? Are you going to claim that the people they were arguing against rejected sola fide also? If so, then what were these people being criticized for? If you think that they did advocate sola fide, then they would be examples of people who held that view between the time of the apostles and the Reformation. I see no reasonable way to deny that some people held sola fide during that timeframe. The quantity of people who did so is more questionable, but the concept that nobody held the view seems to me to be implausible.

I doubt that you would wish to appeal to those against whom the early church fathers wrote. While some were relatively harmless, the majority of polemical work in the early church was directed against serious perversions of the orthodox faith that had been received from the apostles and passed on through the bishorpic leadership of the church. Given this fact, if these individuals against whom the ECF’s wrote did affirm sola fidei, it would seem that this should raise several flags about the philosophical and theological presuppositions which gave rise to not only their heresy, but also their affirmation of sola fidei. Obviously, we cannot conclusively know that this linking was a reality. However, as these heretical individuals would be the ones in whose thinking you would have to locate an explicit affirmation of sola fidei (per your own admission that the “majority” of the orthodox writers did not affirm sola fidei), this should give rise to concern on your part in regards to the tenability of sola fidei. Again, I am not saying that the early heretics affirmed it–but if they did, I would suggest this would be cause for caution, for no theological conclusions are atomistic–rather, the proceed from the same presuppositions which give rise to other conclusions.

The context of 1 Peter 3 is a context primarily about sanctification. He's addressing Christians who are going through some difficulties. Baptism saved them in much the same way that bearing children saves women in a non-justifying sense (1 Timothy 2:15). The term "saved" is used in different ways in different contexts. The public pledge involved in baptism was sustaining these Christians in their trials. It was a means of sanctification. To read 1 Peter 3:21 as a reference to attaining justification through baptism would be unnatural in the context of the passage and would make it contradictory to what Peter and other Biblical authors said elsewhere.

BTW--

The last paragraph of my last post is not mine--I forgot to trim it off.

exist,

you said:

the fact that the historical church never codified sola fidei as an orthodox belief, Protestant theology must be very careful about how forcefully it teaches this concept, lest it (as in many other theological conclusions) effectively marginalize the very tradition to which it attempts to appeal in substantiating its presupposed theological understanding.

Well you must have never read the great Protestant confessions of faith which codify sola fidei as orthodox belief. I'll give you a few examples:

Westminster confession of faith

I. Those whom God effectually calls, He also freely justifies;[1] not by infusing righteousness into them, but by pardoning their sins, and by accounting and accepting their persons as righteous; not for any thing wrought in them, or done by them, but for Christ's sake alone; nor by imputing faith itself, the act of believing, or any other evangelical obedience to them, as their righteousness; but by imputing the obedience and satisfaction of Christ unto them,[2] they receiving and resting on Him and His righteousness by faith; which faith they have not of themselves, it is the gift of God.[3]

II. Faith, thus receiving and resting on Christ and His righteousness, is the alone instrument of justification:[4] yet is it not alone in the person justified, but is ever accompanied with all other saving graces, and is no dead faith, but works by love.[5]

Augsburg Confession

Also they teach that men cannot be justified before God by their own strength, merits, or works, but are freely justified for Christ's sake, through faith, when they believe that they are received into favor, and that their sins are forgiven for Christ's sake, who, by His death, has made satisfaction for our sins. This faith God imputes for righteousness in His sight. Rom. 3 and 4.

2nd Helvetic:

WE ARE JUSFIFIED BY FAITH ALONE. But because we receive this justification, not through any works, but through faith in the mercy of God and in Christ, we therefore teach and believe with the apostle that sinful man is justified by faith alone in Christ, not by the law or any works.

and finally I'll bring in the big gun Clement's epistle to the church of Corinth:

4And we, therefore, who by his will have been called in Jesus Christ, are not justified of ourselves or by our wisdom or insight or religious devotion or the holy deeds we have done from the heart, but by that faith by which almighty God has justified all men from the very beginning. To him be glory forever and ever. Amen.

this point of sola fidei is where the church lives or dies on, and this point let's true believers know who the false teachers are.

Soli deo Gloria, To God alone be the glory.

steven dresen--

Well you must have never read the great Protestant confessions of faith which codify sola fidei as orthodox belief.

Sorry. The "great" Protestant confessions of faith does not qualify as authoritative for orthodox belief because they are not ecumenical. In truly Protestant style, these confessions effectively marginalize nearly the entire scope of Christian history which precedes them. My conscience is not bound in any way to the conclusions of the so-called Protestant "confessions of faith." They may be Protestant, but they are not truly orthodox.

I'll give you a few examples:

Westminster confession of faith

I. Those whom God effectually calls, He also freely justifies;[1] not by infusing righteousness into them, but by pardoning their sins, and by accounting and accepting their persons as righteous; not for any thing wrought in them, or done by them, but for Christ's sake alone; nor by imputing faith itself, the act of believing, or any other evangelical obedience to them, as their righteousness; but by imputing the obedience and satisfaction of Christ unto them,[2] they receiving and resting on Him and His righteousness by faith; which faith they have not of themselves, it is the gift of God.[3]

II. Faith, thus receiving and resting on Christ and His righteousness, is the alone instrument of justification:[4] yet is it not alone in the person justified, but is ever accompanied with all other saving graces, and is no dead faith, but works by love.[5]

Augsburg Confession

Also they teach that men cannot be justified before God by their own strength, merits, or works, but are freely justified for Christ's sake, through faith, when they believe that they are received into favor, and that their sins are forgiven for Christ's sake, who, by His death, has made satisfaction for our sins. This faith God imputes for righteousness in His sight. Rom. 3 and 4.

2nd Helvetic:

WE ARE JUSFIFIED BY FAITH ALONE. But because we receive this justification, not through any works, but through faith in the mercy of God and in Christ, we therefore teach and believe with the apostle that sinful man is justified by faith alone in Christ, not by the law or any works.

These examples are fine and dandy. However, as they are not orthodox declarations of the historic, ecumenical church, I hardly see how they are authoritative or definitive explications of the teaching of the apostles.

and finally I'll bring in the big gun Clement's epistle to the church of Corinth:

4And we, therefore, who by his will have been called in Jesus Christ, are not justified of ourselves or by our wisdom or insight or religious devotion or the holy deeds we have done from the heart, but by that faith by which almighty God has justified all men from the very beginning. To him be glory forever and ever. Amen.

I hardly see that Clement is using "faith" in the way that Protestants do. Rather, he is merely reflecting the teaching of Paul who eschewed the Judaizers' attempts to force Gentiles to become Jewish before they could be justified with God. In the same way, Clement argues here that humans are not justified by doing "x" and "y" and "z" to please God. Nonetheless, this does not substantiate the Protestant bifurcation between "belief" and "action."

this point of sola fidei is where the church lives or dies on, and this point let's true believers know who the false teachers are.

Well, seeing as the church made it just fine for 1500 years before the Protestants came along, I hardly see where the force of your assertion lies.

exist,

You're in error. So I'm going to start with the basics.

This is a good summary of the gospel:

1 Corinthians 15

3For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, 4that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures,

Jesus who is God became a man. He lived a perfect sinless life and he died for our sins. We are saved through faith in Christ, which is based on belief that he died in our place.

The following passage from Romans 10 clarifies the issue further:

10For with the heart one believes and is justified, and with the mouth one confesses and is saved.

We are justified by trusting in the sacrifice of Christ. You want a lie, you want a false gospel, you say you want an ecuminical confession but the fact is that all those positions agree, they define the universal church. To put it bluntly and come to the point, there is going to be a final judgement and if you don't love Jesus and believe he died for you and trust that he was obedient in your place, then you're going to be judged on the basis of your works, and they'll get you condemned because our only hope is Christ anything else is a lie and damnable. I'll be praying that God does work on your heart, and I don't mean that was a smart-alec remark I'm serious, you're on a slippery slope.

Prostestantism has created an unnecessary, unnatural and, IMO, unbiblical bifurction between “faith” and “action.”

To distinguish faith and action is not "bifurcation." They are distinct concepts, as well as being distinct words. The idea of action/works is not part of the semantic range of pistew. More on this below.

It also is not bifurcation to say that faith entails works/action, or faith inevitably causes works/action, but this does not justify a conflation in definition.

Your anti-Protestant diatribe everywhere seems to think (without the benefit of argument) that the only alternative to "bifurcation" is blurring the distinction between concepts.

All orthodox Christians affirm that we are saved by the grace of God.

This affirmation does not absolve semi-Pelagians (affirming the necessity of grace but denying its sufficiency) nor those who make works/actions the co-instrument or co-ground of justification. The Pharisee of Luke 18 credited and thanked God for his good works, but still did not go home justified.

This pericope justifies Jason's comments that the Bible excludes EVERY CONCEIVABLE system of actions or works - not just belonging to the cultus of a particular religion - but even the Pharisee's faithful and just lifestyle, his fasting, and tithing.

has led you to create an unnecessary and inappropriate dichotomy between “faith” and “action.”

For you to say that "action" is not the same thing as "works" is a distinction without a difference. It is still "works" - something we do.

And making a simple distinction (warranted by lexical semantics) between "faith" and "works" is not "dichotomizing", as if we were saying faith and works are not closely related. But works/actions are not co-instruments of justification.

Rather, the argument that is being presented is merely intended to recapture the biblical conception of faith as the integration of belief and action.

Your sloppiness continues. Precisely HOW are belief and action "integrated"? Are you saying that action is included in the definition of faith? As I have already pointed out, you are wrong here. Or, are you saying belief and action evidence genuine faith? Then there is no argument.

God told Abraham to go. What did Abraham do? Did he say, “Ah, I mentally assent in belief to what God has said?” No! He packed his family up and left.

Your ignorance shines brightly as you trot out this old canard. Since you are obviously an Eastern Orthodox types, I suggest you spend some time back in Protestant Doctrine 101, where you will learn that faith is not merely mental assent or unaccompanied by works. From the beginning, Luther stated that 'We are justified by faith alone, but not by a faith that is alone.'

And the Reformed view of faith conceives of faith as being composed of knowledge, assent, and volition:

http://www.girs.com/library/theology/syllabus/subsoter6.html

How does the narrative describe his “faith?” It is action! God told Abraham to go.... The bottom line is that belief and action cannot not separated.

This muddled thinking plagues the rest of your post here. We are not "separating" belief and action by distinguishing them. The Genesis narrative proves that genuine faith will yield and be accompanied by action, but it never defines actions as the essence of faith. It never says nor implies that faith IS action simply because we see that Abraham's faith produces action/works.

this does not mean that faith can be divorced from action. Matthew 25 makes this abundantly clear.

Again, you are trying to justify a blurring of definitions by saying that two concepts cannot be "divorced." That is non sequitur.

perhaps we should use the tradition which we have received to critique our beliefs.

Oh, but which tradition should I pick? Can I pick Clement of Rome?

And we who through his will have been called in Christ Jesus are justified, not by ourselves, or through our wisdom or understanding or godliness, or the works that we have done in holiness of heart, but by faith, by which all men from the beginning have been justified by Almighty God, to whom be glory world without end.

Continuing:

an argument from silence on this issue is hardly compelling and appears, to be perfectly honest, somewhat desperate

Well, that depends. Since there was no concensus, self-conscious, developed doctrine of justification in the early church, one wouldn't weigh the historical issue in the same way as we would with doctrines that were self-consciously developed in light of, say, the early christological controversies. We would expect ambiguity or even silence on such a matter (since the narrower topic of justification does not exhaust the category of salvation).

The "great" Protestant confessions of faith does not qualify as authoritative for orthodox belief because they are not ecumenical.

For us orthodoxy is defined by God's Word, which does not give magical infallible powers to ecumenical councils. You Eastern Orthodox types everywhere assume such powers, but never prove it.

It also has the pragmatic difficulty of justifying any innovative heresy beyond the 1st-millennium ecumenical councils as being within the pale of orthodoxy.

Even so, the "historic" interpretation you give so much lip service to of justification hardly backs up your 20/21st century Sanders/Dunn/Wright New Perspectivist take on the biblical texts.

Some more "gems" from exist-dissolve:

I hardly see that Clement is using "faith" in the way that Protestants do.

Oh? How is it different?

Rather, he is merely reflecting the teaching of Paul who eschewed the Judaizers' attempts to force Gentiles to become Jewish before they could be justified with God.

This is indeed a sad and desperate way to wiggle out of a fairly plain text. He does not contrast "faith" with "the Judaizer's attempts to force Gentiles to become Jewish." That is nowhere in the context. Rather, the explicit contrast is between faith and "our wisdom or understanding or godliness, or works that we have done in holiness of heart."

In the same way, Clement argues here that humans are not justified by doing "x" and "y" and "z" to please God. Nonetheless, this does not substantiate the Protestant bifurcation between "belief" and "action."

If all you have to fall back on is the hollow rhetoric about "bifurcation", you have no case. How is it "bifurcation" to say that "faith" and "action/works" are different concepts, as well as different words, that serve different functions in a given text?

You need to give your rhetoric some feet here.

steven dresen--

You're in error.

Oh. Ok.

So I'm going to start with the basics.

This is a good summary of the gospel:

1 Corinthians 15

3For I delivered to you as of first importance what I also received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the Scriptures, 4that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures,

Jesus who is God became a man. He lived a perfect sinless life and he died for our sins. We are saved through faith in Christ, which is based on belief that he died in our place.

The following passage from Romans 10 clarifies the issue further:

10For with the heart one believes and is justified, and with the mouth one confesses and is saved.

We are justified by trusting in the sacrifice of Christ. You want a lie, you want a false gospel, you say you want an ecuminical confession but the fact is that all those positions agree, they define the universal church. To put it bluntly and come to the point, there is going to be a final judgement and if you don't love Jesus and believe he died for you and trust that he was obedient in your place, then you're going to be judged on the basis of your works, and they'll get you condemned because our only hope is Christ anything else is a lie and damnable. I'll be praying that God does work on your heart, and I don't mean that was a smart-alec remark I'm serious, you're on a slippery slope.

What in the world does this have to do with anything I have posted? Like many others on this board, instead of actually engaging my point, you fall back on pat propositional answers that you feel somehow contradict what I have said even though they do not even approach the content of my ideas. You say I am on a slippery slope, yet you do not bother to show me how, except to rehearse some entirely unrelated litany of propositional statements.

To distinguish faith and action is not "bifurcation." They are distinct concepts, as well as being distinct words. The idea of action/works is not part of the semantic range of pistew. More on this below.

I firmly disagree. "Pistew", like all other words, does not have absolute meaning. Rather, the meaning is derived from the context in which it is used and the place that is assumes in the course of description. Therefore, it would be linguistically absurd to limit the range of meaning of a word, given the fact that all "definitions" are ultimately derived from presuppositions about the ways in which the words are used.

It also is not bifurcation to say that faith entails works/action, or faith inevitably causes works/action, but this does not justify a conflation in definition.

Again, you are operating from a presupposition about the possible semantic meaning of "faith" because of your theological convictions, even as I do.

Your anti-Protestant diatribe everywhere seems to think (without the benefit of argument) that the only alternative to "bifurcation" is blurring the distinction between concepts.

There need not be an absolute "blurring." Nonetheless, there is also no reason to create a bifurcation which is exactly what Protestant theology does with "belief" and "action" because of its wrongheaded understanding of Paul's polemic against "works."

This affirmation does not absolve semi-Pelagians (affirming the necessity of grace but denying its sufficiency) nor those who make works/actions the co-instrument or co-ground of justification. The Pharisee of Luke 18 credited and thanked God for his good works, but still did not go home justified.

You just can't resist a shot at semi-Pelagianism, can you? My post has nothing to do with semi-Pelagianism, Pelagianism, or any of the like. Moreover, in this post, you continue in your misunderstanding of my post by wrongly bifurcating faith and action. I have never said that we are justified by works. However, belief is action, and action is belief. The Pharisee in your example was not justified precisely because he had the kind of bifurcated faith which you advocate; he assented to belief in God, yet failed to do those things which were pleasing to God (helping the poor, giving justice to the widow, etc).

This pericope justifies Jason's comments that the Bible excludes EVERY CONCEIVABLE system of actions or works - not just belonging to the cultus of a particular religion - but even the Pharisee's faithful and just lifestyle, his fasting, and tithing.

But the Pharisee did not have a "faithful and just" lifestyle. His morality was entirely inwardly focused; he believed he was justified because of what he did. What brings justification, however, is obedience to the will of God, as seen clearly in the examples of all the "faithful" of God throughout history, including Jesus. Jesus was vindicated by the Father, not because he "believed," but rather because he was faithful to do the will of God, even as Abraham before him was.

For you to say that "action" is not the same thing as "works" is a distinction without a difference. It is still "works" - something we do.

Yes, but they are not the same. To "do" something is necessary--we are embodied creatures. Therefore, we cannot "think" or "believe" without "doing." The difference, then, between "action" and "works" is that the latter supposes that justification is based upon fulfilling in oneself a system of works that is self-justifying. The other (action) is simply the natural response of the human person to the grace of God.

And making a simple distinction (warranted by lexical semantics) between "faith" and "works" is not "dichotomizing", as if we were saying faith and works are not closely related. But works/actions are not co-instruments of justification.

Again, as we are integrated beings, it is impossible that they are not concomitant. To suppose that one can have "faith" without "action" is ultimately a gnostic conception of belief, a position which has been thoroughly and consistently rejected by the historic Christian church. Moreover, it is a concept that is entirely foreign to the biblical witness. If one looks at any example of "faith" in the Scriptures, it is clear that the meaning goes much farther than some metaphysical conception of "belief." Rather, it faith is a description of obedience.

Your sloppiness continues. Precisely HOW are belief and action "integrated"? Are you saying that action is included in the definition of faith? As I have already pointed out, you are wrong here. Or, are you saying belief and action evidence genuine faith? Then there is no argument.

I am saying that belief and action comprise the definition of faith. You may claim that semantically this is unwarranted. However, I think if the definition is expanded to allow for an honest examination of the meanings which are assumed by the writers who employed "faith" language, the intergrated nature of faith will become immediately honest. Unfortunately, it is extremely difficult to find any Protestant literature that deals in an intellectually honest way with this concept, for the hegemony of sola fidei has so poisoned the intellectual arena of Protestantism that the assumption is all but automatic by all who approach the subject.

Your ignorance shines brightly as you trot out this old canard. Since you are obviously an Eastern Orthodox types