Posted by Phil Johnson

any have failed to understand how everything, from the smallest event to the greatest, can be ordained and fixed, and yet how it can be equally true that man is a responsible being, and that he acts freely, choosing the evil, and rejecting the good.

any have failed to understand how everything, from the smallest event to the greatest, can be ordained and fixed, and yet how it can be equally true that man is a responsible being, and that he acts freely, choosing the evil, and rejecting the good.

Many have tried to reconcile these two things, and various schemes of theology have been formulated with the object of bringing them into harmony. I do not believe that they are two parallel lines, which can never meet; but I believe that, for all practical purposes, they are so nearly parallel that we might regard them as being so. They do meet, but only in the infinite mind of God is there a converging point where they melt into one. As a matter of practical, everyday experience with each one of us, they continually melt into one; but, so far as all finite understanding goes, I do not believe that any created intellect can find the meeting-place. Only the Uncreated as yet knoweth this.

Many have tried to reconcile these two things, and various schemes of theology have been formulated with the object of bringing them into harmony. I do not believe that they are two parallel lines, which can never meet; but I believe that, for all practical purposes, they are so nearly parallel that we might regard them as being so. They do meet, but only in the infinite mind of God is there a converging point where they melt into one. As a matter of practical, everyday experience with each one of us, they continually melt into one; but, so far as all finite understanding goes, I do not believe that any created intellect can find the meeting-place. Only the Uncreated as yet knoweth this.

It would be a very simple thing to understand the predestination of God if men were clay in the hands of the potter, and nothing more. That figure is rightly used in the Scriptures because it reveals one side of truth; if it contained the whole truth, the difficulty that puzzles so many would entirely cease. But man is not only clay, he is a great deal more than that, for God has made him an intelligent being, and given him understanding and judgment, and, above all, will. Fallen and depraved, but still not destroyed, are our judgment, our understanding, and our power to will; they are all under bondage, but they are still within us.

If we were simply blocks of wood, like the beams and timbers in this building, it would be easy to understand how God could prearrange where we should be put, and what purpose we should serve; but it is not easy—nay, it is difficult,—I venture to say that it is impossible for us to understand how predestination should come true, in every jot and tittle, fix everything, and yet that there should never be, in the whole history of mankind, a single violation of the will, or a single use of constraint, other than fit and proper constraint, upon man, so that he acts, according to his own will, just as if there were no predestination whatever, and yet, at the same time, the will of God is, in all respects, being carried out.

In order to get rid of this difficulty, there are some who deny either the one truth or the other. Some seem to believe in a kind of free agency which virtually dethrones God, while others run to the opposite extreme by believing in a sort of fatalism which practically exonerates man from all blame. Both of these views are utterly false, and I scarcely know which of the two is the more to be deprecated. We are bound to believe both sides of the truth revealed in the Scriptures, so I admit that, when a Calvinist says that all things happen according to the predestination of God, he speaks the truth, and I am willing to be called a Calvinist; but when an Arminian says that, when a man sins, the sin is his own, and that, if he continues in sin, and perishes, his eternal damnation will lie entirely at his own door, I believe that he also speaks the truth, though I am not willing to be called an Arminian.

The fact is, there is some truth in both these systems of theology; the mischief is that, in order to make a human system appear to be complete, men ignore a certain truth, which they do not know how to put into the scheme which they have formed; and, very often, that very truth, which they ignore, proves to be, like the stone which the builders rejected, one of the headstones of the corner, and their building suffers serious damage through its omission.

Now, brethren, if I could fully understand these two truths, and could clearly expound them to you,—if I could prove to you that they are perfectly consistent with one another, I should be glad to do so, and to escape the censures which some people constantly pour upon those who are trying to preach the whole of revealed truth; but it is more than my soul is worth for me to attempt to alter and trim God's truth so as to make it pleasing to men. I preach it as I find it in God's Word; I am not responsible for what is in the Book, I am only responsible for telling out what I find there, as it is taught to me by the Holy Spirit.

But mark this; to the mind of God, there is no difficulty concerning these two truths, though there is, to us, so much mystery and perplexity. It is all simple enough to him; he is omnipotent in the world of mind as well as in the world of matter; and he is omniscient, he knows everything, he foresees everything, so that there are no difficulties to him.

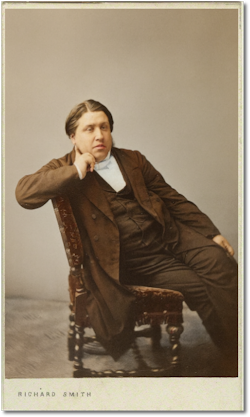

This excerpt is taken from Charles Haddon Spurgeon, sermon # 2862, "The Way of Wisdom" in The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit (London:Passmore & Alabaster, 1903) 49:601. This sermon was originally preached on Thursday Evening, 28 March 1872 at the Metropolitan Tabernacle, London.

2 comments:

Thanks for posting this Phil, glad to see fresh old stuff on the blog!

Seems Spurgeon used the "parallel truths" in his "A Defense of Calvinism" sermon where he described them as, intersecting at the throne of God, if my memory serves me correctly! Great stuff.

Thanks again,

You basically stated the Lutheran position. I agree wholeheartedly. God bless and thanks for the post.

Post a Comment