rior to the middle of the 19th century, burial of the dead usually took place in churchyards. These were small, often overcrowded burial grounds—especially those that got severely squeezed by urban development.

rior to the middle of the 19th century, burial of the dead usually took place in churchyards. These were small, often overcrowded burial grounds—especially those that got severely squeezed by urban development.

London in particular had this problem. The city was well known for the powerful stench that emanated from sewage in the Thames. Foul odors that wafted into the atmosphere from decaying bodies in shallow churchyard graves added to the fetid ambience of the city. Londoners believed the nauseating odor that hung in the air over their communities carried infection. "Bad air," known as the miasma, was commonly believed to be a major factor in the spreading of disease.

In Europe and America, city planners began to build rural cemeteries—parklike acreages located (at the time) well outside the city limits. London, for example, built seven expansive burial parks circling the city (dubbed "the Magnificent Seven" sometime in the 1980's). One of these was the West Norwood Cemetery, where Charles Spurgeon would be buried in early 1892.

Crowded cemeteries such as Bunhill Fields and most churchyard burial grounds within the city limits were closed by the Burial Act of 1852. Then during the 1854 cholera epidemic, a physician, John Snow, proved that the disease was not airborne; it was spread by contaminated water. Ground-water pollution was the result of poor management of London's sewage. Cesspools, slaughterhouses, and other sources of wastewater were draining into the aquifer, contaminating well water. That was the real culprit—not the air, and not old graveyards.

By the 1870s, England's Funeral Reform Movement had turned its attention to the extravagant costs and pretentious pageantry associated with typical Victorian funerals. These were lavish formal affairs with professional mourners (known as "mutes"), who followed ornate hearses festooned with ostrich plumes, carrying expensive coffins. Mourners were expected to wear formal clothing made of black crepe and march in procession to the burial. Burial monuments were often large, heavily ornamented stone structures. The cost of a "decent" burial could bankrupt a working-class family.

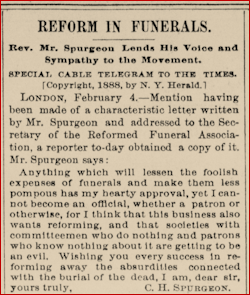

Funeral Reform activists lobbied and campaigned for more modest, less expensive, more simplified ceremonies. The movement soon became noisier and more aggressive, and they solicited Spurgeon's influence in support of their efforts. He replied in his typically elegant fashion, indicating frankly that while he was fully sympathetic with the cause, he did not want to be associated with the reputation or rhetoric of the movement. He gently suggested that the movement itself could use some reform.

Funeral Reform activists lobbied and campaigned for more modest, less expensive, more simplified ceremonies. The movement soon became noisier and more aggressive, and they solicited Spurgeon's influence in support of their efforts. He replied in his typically elegant fashion, indicating frankly that while he was fully sympathetic with the cause, he did not want to be associated with the reputation or rhetoric of the movement. He gently suggested that the movement itself could use some reform.

This type of gentlemanly candor is one of the features of Spurgeon's style that I appreciate most. The Philadelphia Times (February 5, 1888), p. 2 carried his reply:

Anything which will lessen the foolish expenses of funerals and make them less pompous has my hearty approval, yet I cannot become an official, whether a patron or otherwise, for I think that this business also wants reforming, and that societies with committeemen who do nothing and patrons who know nothing about it are getting to be an evil. Wishing you every success in reforming away the absurdities connected with the burial of the dead, I am, dear sir, yours truly.

No comments:

Post a Comment